Newly unredacted court filings show that Google may have leveraged its end-to-end control over the auction-driven display advertising market to unfairly funnel revenues away from publishers and competing advertising exchanges, and back to itself, to the tune of $250 million in annual revenue dating back to 2013.

The crux of this alleged manipulation involves Google publicly stating that its auction system used a second-price model, when in fact it may have actually been using a third-price model — at least when it suited Google.

To illustrate, using the display advertisements on PJ Media as a theoretical example, let’s say the following consumer product brands each enter into an auction to place its advertisement on PJMedia.com: MyPillow, Black Rifle Coffee, and ExpressVPN.

MyPillow bids $10, Black Rifle Coffee bids $6, and ExpressVPN bids $2.

In an auction using a first-price model, MyPillow wins and pays $10 for its advertisement. Google takes a 20% cut for serving the advertisement, and PJ Media is distributed $8.

In a second-price model, MyPillow still wins, but they only pay whatever the second-highest bid was — in this case, the $6 bid placed by Black Rifle Coffee. Google again takes its 20% cut, and PJ Media is issued $4.80.

And finally, in a third-price model, MyPillow again wins, but it pays only $2, the third-highest bid as placed by ExpressVPN. Google takes its cut, and PJ Media is left with just $1.60.

Extrapolate that out over millions of auctions, and you can see how a third-price model instead of a second-price model would operate to the significant detriment of publishers, which are often small businesses.

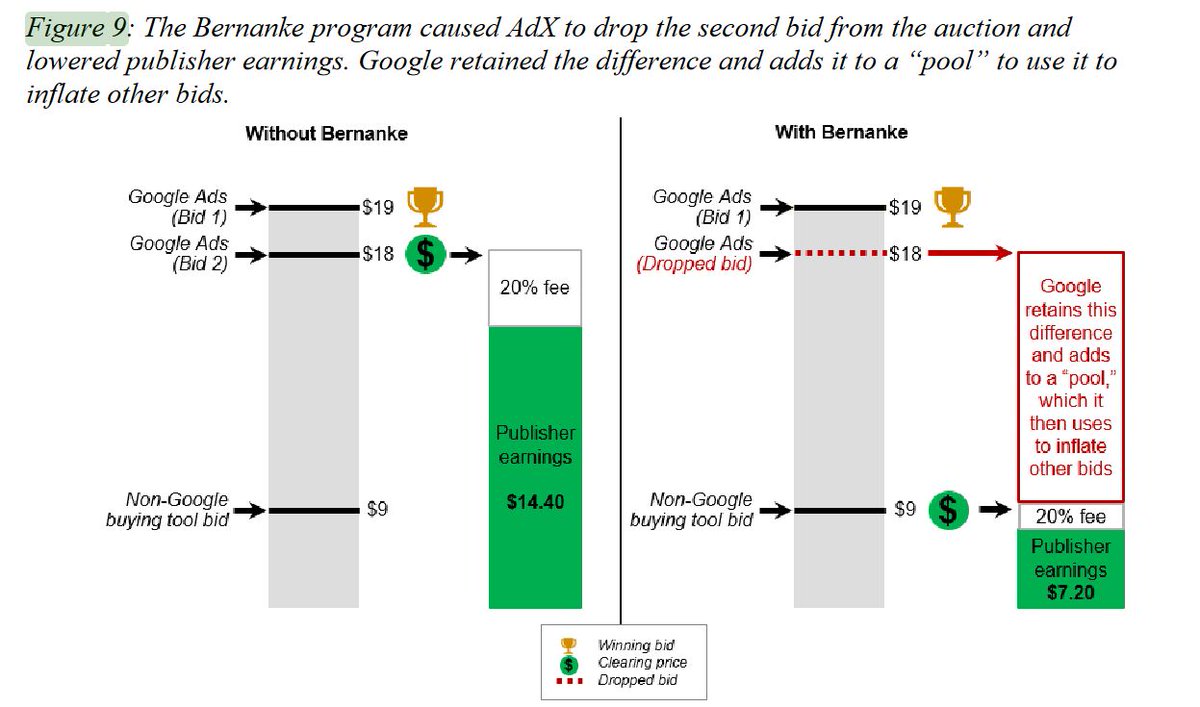

Now, as you likely noticed, the use of a third-price model would cut into Google’s 20% take as well, and that is where things get interesting. On the publisher side, Google would use the third-price model, but on the advertiser side, the second-price model would come into effect. So advertisers pay the full second price, but publishers get compensated only on the third price.

This model differential created an excess pool of money, a pool that Google allegedly would then later tap into in order to inflate bids that were placed exclusively with its own ad exchange, called AdX — a privilege that would be unavailable to other competing ad exchanges.

And it is that notion — leveraging complete market dominance in one area to tip the scales unfairly in another area — that has attracted antitrust scrutiny.

Related: ‘Hey Google, Sing Me Some Vaccination Propaganda’

The program as described above became known as Project Bernanke at Google, named after the former Federal Reserve chair who endorsed injecting extra money into the economy, a policy that may have inspired Google to inflate bids placed with its own ad exchange. Here is a diagram of Project Bernanke as shared out by Leah Nylen of Politico:

Initially, Google reportedly kept track of how much money was being withheld from publishers, and would then pay it back. But later versions of Bernanke dropped this delayed payback functionality.

Many in the publishing and advertising industries have suspected foul play on the part of Google for years, and those suspicions increasingly appear to have been valid.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member