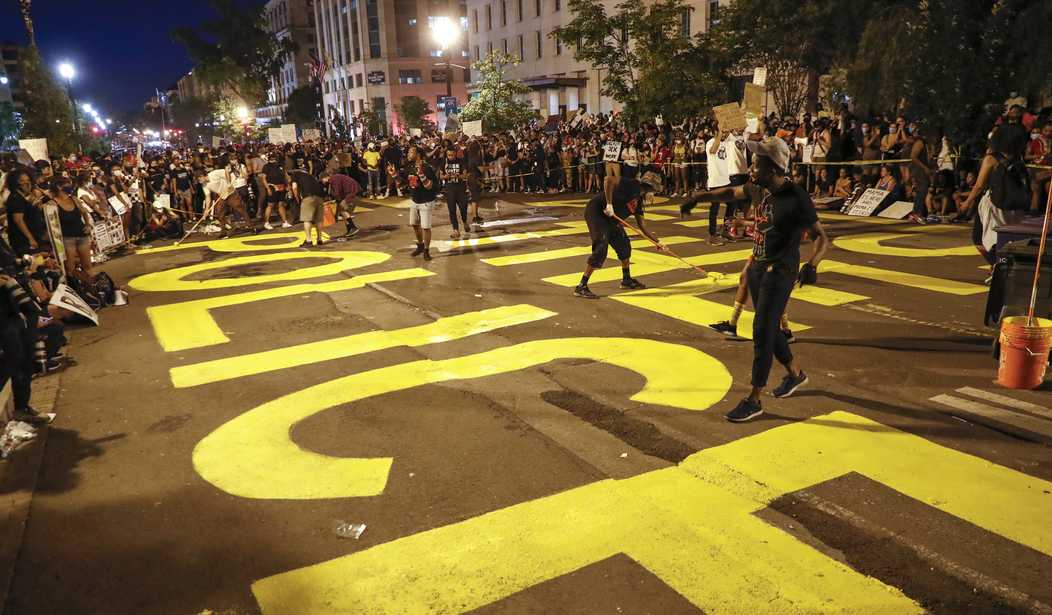

As the destructive and deadly riots over the horrific police killing of George Floyd draw to a close, Black Lives Matter groups have demanded that cities “defund the police” and many cities have taken up the call, including the Minneapolis City Council and Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti. But what would actually happen if cities defunded the police? Do activists expect the police to simply “go away?” Do they think defunding law enforcement will make the cops and their alleged racism simply vanish?

Reason‘s Scott Shackford, who supports decreasing police department funding, urges caution in the way cities should go about it.

As it turns out, an effort to defund the police can backfire and harm the very people Black Lives Matter wants to help.

Where will the police get the money?

If cities defund the police, that won’t necessarily abolish the departments. In fact, the remaining police departments may suddenly have an added incentive to crack down on ordinary citizens.

As Shackford notes, “If you don’t account for revenue from fines, fees, and forfeiture, this can all backfire against the poor.”

Police departments across the country are partially funded by fees and fines that suspects pay when they are arrested for a crime. Some police departments are even able to keep some or all of the money or property they seize from suspects during an arrest. Under civil asset forfeiture, police seize people’s money, homes, and vehicles through court proceedings by simply accusing the owners of having earned the money or purchased the property through illegal means.

Police can do this even without a court conviction.

During the 2009 recession, revenue collection in cities across America dropped, and police responded by increasing the use of civil asset forfeiture to maintain their budgets. As Shackford noted, “The targets of asset forfeiture are frequently low-income minorities and immigrants who lack the resources to fight back.”

While some states and localities have reformed civil asset forfeiture, Democrats in Arizona shot down one such reform just last month — because the change would deprive police departments of revenue. If cities defund the police, expect more civil asset forfeiture as a response.

More fines and fees

Some cities depend on fines and fees, turning the police into “an especially nasty sort of tax collector,” Shackleford noted. “In the wake of the Michael Brown shooting in Ferguson, Missouri, black residents in several St. Louis-area communities railed against these small regimes of petty fines for extremely minor crimes and the harsh code enforcement systems that tried to extract homeowners’ money over tiny violations.”

The Institute for Justice investigated these harsh systems in all fifty states and found some utterly despicable practices cities use to raise money.

The report began with the story of 88-year-old Mildred Bryant, a resident of St. Louis suburb Pagedale, Mo. In 2015, the city threatened Bryant with 12 municipal code violations for petty “crimes” like not having matching curtains or slats on her home’s windows. Although Pagedale has only 3,000 residents in its one square mile of land, the city wrote more than 32,000 citations between 2010 and 2016. The fines from these citations and related fees accounted for nearly 25 percent of the city’s revenue in some years. These fees formed the city’s second-largest source of income for years.

Bryant and other Pagedale residents brought a federal class-action lawsuit against the city, which resulted in a consent decree to reform the city’s ticketing practices. Yet the IJ report found that some communities depend on fees and fines to raise as much as 30 percent of their budgets!

While a move to defund the police may decrease the number of cops enforcing petty fines and fees, it is likely cities will find a loophole in order to keep this money flowing. Expect police to receive a cut from fines and fees — if they don’t already! — and expect more petty laws to criminalize innocent behavior in an effort to keep the money flowing.

Who will enforce the laws?

It seems rather ironic that the very same activists who demand cities defund the police also want an expansive government to impose limitations on the free market and redistribute wealth. When many angry protesters turned to loot a Target near the police precinct in Minneapolis, that destruction of property wasn’t just convenient — it was an expression of a terrifyingly mainstream rejection of the very notion of property and the rule of law.

Yet if the government is going to crack down on the free decisions of free people to start businesses, provide goods to other people, and freely choose what goods to buy, it will have to use some force to maintain this regime. Without police, who will enforce the higher taxes on gasoline, the extra regulations for business owners, or the government-mandated standards for all sorts of goods and services? You can’t have an expansive “progressive” bureaucracy without an enforcement mechanism.

The essential function of the police is to defend the life, liberty, and property of the citizens and to enforce the rule of law. Many of the state and local laws the police enforce are unjust and should be repealed, and many police unjustly enforce them. But that does not mean abolishing the police is the path toward restoring justice — quite the opposite.

Take the Black Lives Matter case of Eric Garner, for instance. New York cops killed him in part due to suspicions he was holding and selling “loosies” — black market loose cigarettes. “Loosies” are a problem because New York City levies high taxes on cigarettes in order to raise revenue, so a black market sprang up in response to the taxes.

Similarly, while states like California and Colorado have legalized marijuana, they still have massive black markets in pot because cities and states have piled on so many taxes. As Shackford argued, “The reasons the government is policing people have changed (‘Drugs are bad!’ becomes ‘You’re not licensed!’), but the people being targeted really haven’t. The people most likely to fined or arrested by police are those who can’t afford the cost that cities are demanding of them.”

Petty government controls extend to licensing, too. Nail salons and hair salons have to navigate a labyrinth of red tape supposedly in the name of helping consumers.

The police did not vote for these taxes. The police do not slap regulations on businesses. But the police are called upon to enforce them because the job of the police is to uphold the rule of law. When police enforce arguably unjust laws, it’s not the police’s fault — it’s the government’s fault.

Scaling back civil asset forfeiture, fees, taxes, and regulations would make it easier for poorer citizens to find jobs, avoid crime, and live better lives. Defunding the police isn’t the solution, reforming the laws and reforming police practices — especially civil asset forfeiture and plainclothes “no-knock warrants” — must form key parts of any solution.

The problem is, cities don’t want to give up the money. They’re more than happy to pass a virtue-signaling promise to defund the police, but don’t you dare question how their bread and butter comes from taking advantage of the most vulnerable! City officials are more than happy to make the police the scapegoat.

Tyler O’Neil is the author of Making Hate Pay: The Corruption of the Southern Poverty Law Center. Follow him on Twitter at @Tyler2ONeil.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member