Update below.

Over the past two years, the far-left Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) has faced numerous lawsuits for defamation and other claims. The SPLC earned its reputation by suing the Ku Klux Klan, and in recent decades it has accused various organizations of being “hate groups,” listing them along with the KKK in a cynical attempt to raise money and destroy its political enemies. While the SPLC paid a $3.375 million settlement to Muslim reformer Maajid Nawaz last year, none of the many lawsuits against the SPLC has threatened to reveal its secrets — until now.

Every lawsuit against the SPLC has been stalled or dismissed or settled, with none reaching the discovery process — a legal process by which a plaintiff can investigate the internal documents of the organization or person he or she is suing. On Tuesday, a judge dismissed a Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) lawsuit, claiming CIS attempted to shoehorn a defamation claim into a racketeering claim. CIS Executive Director Mark Krikorian told PJ Media his group is considering an appeal.

The discovery process threatens to reveal the SPLC’s hidden documents. This is a big deal because the organization had a serious shake-up in March, when it fired its co-founder and cleaned house at the top in response to claims of sexual harassment and racial discrimination. The secretive SPLC did not even reveal the employee letter that led to this massive shake-up, and there is likely more dirt still to be uncovered.

In July, District Court Judge Roseann Ketchmark in the Western District of Missouri rejected part of the SPLC’s motion to dismiss a defamation lawsuit, allowing the case to enter the discovery process. Yet this huge news has received almost no media attention, presumably because there is no big law firm behind this lawsuit.

In Craig Nelsen v. Southern Poverty Law Center, the Kansas City-based pro se plaintiff Craig Nelsen is suing the SPLC for defamation and asking $4.755 million in damages. Nelsen, a former heroin addict, had started the Robinson Jeffers Boxing Club (RJBC), a 13-week residency “life treatment” program for men with opioid addictions or who are otherwise in distress. The program called for a healthy diet, morning exercise, and a rigorous academic program with math, philosophy, literature, music, history, and poetry. The core of the program centered on a daily two-hour intensive boxing training, in order to give men confidence to face the world.

Nelsen attempted to start the program in late 2017 in the small town of Lexington, Mo., with specifically white males in mind. Yet RJBC was always open to people of all races, and Nelsen had made that clear from the get-go.

According to the lawsuit, Nelsen “expressed his theory that, as evidenced by official statistics on suicide and opioid abuse, white males were in a crisis of self-loathing. He argued that the Robinson Jeffers Boxing Club—designed to address the particular challenges faced by white males in modern America—could save lives, repair broken families, and help alleviate the ocean of suffering across the country.”

On his website and in literature for RJBC, Nelsen made it clear that while the program was “designed to address the specific challenges unique to white males in the United States, the program was open to, and would benefit, men in distress of any race.”

Unfortunately, some Lexington residents got the wrong impression, fearing that RJBC was a white supremacist organization. This was absurd, since Sherman Davis, a black resident of Washington, D.C., came to Lexington to help Nelsen launch the program. The lawsuit notes that it is “impossible to imagine that Davis, an African-American, would uproot himself from his home town and set out with Nelsen on a journey halfway across the country in the dead of winter on a speculative effort to establish a beachhead for white supremacy.”

Yet Lexington resident Deborah Starke Bullock found 15- to 20-year-old SPLC attacks against Nelsen, which claimed he was an anti-immigrant racist supported by neo-Nazis. She shared them on a Facebook group and ginned up a mob against Nelsen. The SPLC piled on with a new article restating the old attacks and claiming that Nelsen “isn’t convincing anyone” that his club is open to non-whites.

The backlash was deafening. A popular football coach who had supported RJBC and made a fundraising video for the program denounced Nelsen and said he had been hoodwinked. The City of Lexington filed a stop-work order — even though Nelsen hadn’t started renovating the site for RJBC, a former grocery store. Pat Welch, the owner of the property and a supporter of the project, said it was time to throw in the towel.

During this public battle, Nelsen and Davis met Ryan Wilson, a 24-year-old man described in the lawsuit as “intelligent, addicted to heroin, and the father of an infant boy.” He was excited about RJBC. It was a cold night, and Nelsen wanted to invite Wilson to spend the night in the store, but decided against it — since residents had posted online messages saying they would take matters into their own hands if the city would not get rid of the “Nazis on Main St.” He thought taking Wilson in would give the authorities an excuse to arrest him.

Wilson was killed by a hit-and-run driver that evening.

“In the wake of Wilson’s death, Nelsen and Davis’s frustration grew at the sheer needlessness of it. He and Davis had traveled to Lexington expressly to help distressed men like Wilson, but had been prevented for political reasons—reasons supplied primarily by the SPLC’s and Bill Sellers’ false and defamatory statements. It was an outrage that the SPLC could do so much damage with such impunity,” the lawsuit states.

After an aborted attempt to launch RJBC in Baltimore, Davis returned to D.C. and Nelsen lived in his van on the streets of Baltimore. The SPLC attack has done Nelsen continued damage, as potential business partners have googled his name and discovered the SPLC article.

Last November, Nelsen sued the SPLC on six counts of defamation, claiming the SPLC attempted to slander him as a neo-Nazi, anti-immigrant, and racist — and specifically accusing him of opening a whites-only club.

Judge Ketchmark struck down the suggestions that Nelson is a neo-Nazi, anti-immigrant, and racist, but she allowed Nelsen’s lawsuit to move forward on the SPLC’s false claim that Nelsen was opening a whites-only club.

Indeed, the article reads, “Nelsen claimed the club is open to all races, but he isn’t convincing anyone.” The lawsuit dissects this sentence in detail, explaining that the sentence is a blatantly false assertion of objective fact. Not only was the SPLC accusing Nelsen of lying, but that statement arguably revealed actual malice against the former addict.

According to the lawsuit, the SPLC knew that statement was false, since the article concluded with this sentence: “The meeting drew a large crowd, but in the week since, Nelsen has only resorted to getting in virtual boxing matches with residents and his grand plan for Lexington remains, at least for now, between rounds.”

According to the lawsuit, the SPLC “could only make the statement if it was monitoring the Facebook group” where the debate about RJBC was taking place. “Among those participating in the Facebook discussion were those who counseled a more moderate position, who had read the website, recognized the potential for good and the undeniable need for something to be done, and who pointed out that the RJBC was open to men of any race. In other words, they were ‘convinced’ by [Nelsen]. Therefore, [the SPLC] knew that its claim that [Nelsen]wasn’t convincing anyone was false.”

The SPLC embedded this allegedly defamatory claim in an article insinuating that Nelsen is anti-immigrant, racist, and neo-Nazi. Nelsen had run the group ProjectUSA, which advocated for an immigration time-out to give the “assimilation magic a chance to work.” According to Nelsen, the U.S. has experienced many waves of immigration, often punctuated by a time-out period allowing immigrants to assimilate.

“Organizations like the Southern Poverty Law Center label those who advocate for remaining true to the traditional immigration pattern as hate groups and extremists and stealth Nazis,” Nelsen claims in the lawsuit. He notes that the SPLC savages “anyone who suggests a time-out or any reduction at all in either legal or illegal immigration as anti-immigrant and a ‘hate group.'”

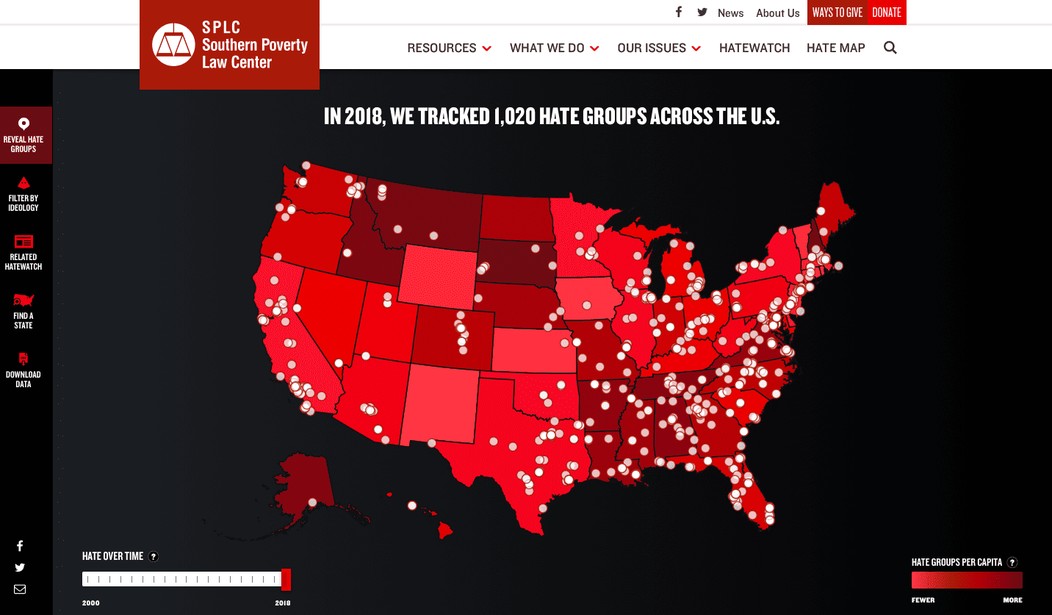

Indeed, the SPLC attacks a broad swath of organizations as “anti-immigrant hate groups.” The article attacking Nelsen notes that he sat on the advisory board for the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), which the SPLC accuses of being a “hate group.”

“The SPLC seems to think that any deviation from their political ideology amounts to hate,” FAIR Media Director Ira Mehlman told PJ Media. While the SPLC goes to great lengths to connect FAIR with racism, Mehlman insisted that “there’s nothing in FAIR’s record that we discriminate for or against any immigration based on race, religion, ethnicity. We believe immigration needs to be more limited, that people need to obey our laws and we need an immigration policy that selects people based on some rational basis, they need to contribute.”

He insisted that FAIR welcomes “qualified people” from “just about any place on Earth.”

Interestingly, the SPLC attack on Nelsen does not just note his connection with FAIR but also cites a Lexington resident who compared Nelsen to a neo-Nazi who moved to North Dakota to set up a colony. As the lawsuit notes, this is “not only guilt by association, it’s guilt by association even where there is no association.”

Nelsen’s entering the discovery process has huge implications for lawsuits against the SPLC. In addition to Nelsen and CIS, D. James Kennedy Ministries, Baltimore lawyer Glen Keith Allen, and Proud Boys founder Gavin McInnes have sued the far-left group.

Mat Staver, founder and chairman of Liberty Counsel, a Christian nonprofit branded a “hate group” by the SPLC, told PJ Media that more than 60 organizations are considering their own lawsuits against the SPLC. He said Nelsen’s lawsuit will likely “bolster other cases; there’s no question about it.”

Staver noted that any documents Nelsen files in court are public record for others to inspect, report on, or use in other lawsuits — unless they’re sealed.

After CIS filed its RICO lawsuit, the SPLC asked the court to penalize CIS for filing a frivolous lawsuit. While the judge struck down the lawsuit, she did not say it was frivolous and did not penalize CIS. This development also bodes well for those considering a lawsuit against the SPLC.

“I think that the SPLC itself is inspiring more people to file lawsuits by its reckless labeling of people ‘hate groups,'” Staver told PJ Media. “The SPLC is the real inspiration for these lawsuits.”

He noted that litigation often follows a “typical pattern of suits that were not successful and then began to get some traction and eventually began to get a significant amount of traction.”

Citing the SPLC’s settlement with Nawaz, Staver said the lawsuits against the SPLC may be crossing the threshold. “There’s more traction building,” he insisted.

Update September 20, 10:40 a.m.: A judge struck down the D. James Kennedy Ministries lawsuit against Amazon and the SPLC on Thursday. An appeal is expected.

Follow Tyler O’Neil, the author of this article, on Twitter at @Tyler2ONeil.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member