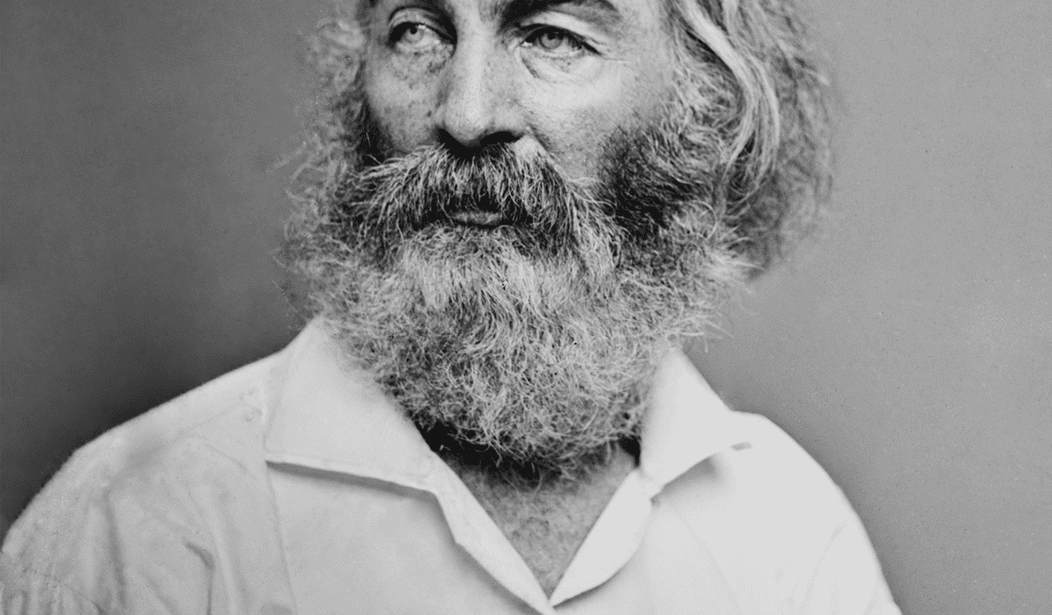

May 31, 2019, was the two hundredth anniversary of Walt Whitman’s birth, and the cities of Camden and Philadelphia spearheaded a number of fascinating celebrations.

It was the poet Walt Whitman after all, who wrote, “I am large, I contain multitudes.” That sentence, when one thinks about it, can mean almost anything. Walt Whitman can be anything or “anybody” you want him to be. Theoretically, that means he can be a leftist progressive social justice warrior, a Trump supporter, a heterosexual, bisexual, homosexual or all three boiling over in a rich pansexual mix. Or, barring that, he can be none of these and his homoerotic poetry in Leaves of Grass can all be just a pose, a stage front behind which you will find a celibate, asexual old man. Whitman has always kept people guessing as to who or what he was; the net result of this is that people keep coming up with different answers. All of which may be correct since the poet “contains multitudes.”

My interest in Whitman began long before I visited the Walt Whitman house on Mickle Street in Camden in the early 1980s when the only tour guide there was an elderly woman. The guide knew everything about the poet. She knew that he was six foot tall and weighed 200 pounds, and that after his death in the Mickle Street bedroom an autopsy was performed downstairs. She also knew that after the autopsy Whitman’s brain, which weighed about 43.3 ounces, was preserved for a while in a jar but came to an unlucky end when the jar fell from the arms of a careless lab attendant. Fragments of the brain were somehow lost and that was that.

During my tour, I touched Whitman’s slippers, his rocking chair and a host of other artifacts in the house—something that you cannot do today because all these things have been relegated to a NO Touch zone. No sooner were we in the poet’s bedroom when the guide began to talk about Mary Oakes Davis who lived with Whitman as a housekeeper. I had read in books and journals and even in the 1982 issue of Partisan Review [containing the essay, “Whitman and the politics of Gay Liberation”] that I had under my arm during the tour, that Davis’ love for Walt was non-reciprocal, but here in the poet’s bedroom I was being told that the love was mutual, rich, passionate and had the essence of a real love affair and that all those other things, the stories about men and stagecoach boys and his closest comrade, Peter Doyle, were fabricated myths designed to turn a great poet into an Old Testament sodomite.

I am large, I contain multitudes. We cannot forget this line. It is the most important, perhaps, of the poet’s career.

I told the guide that the poet loved a number of young men, including Peter Doyle the former Washington D.C. streetcar conductor, although I stayed away from the not so pleasant story of when Whitman was a young school teacher in Long Island and had to deal with accusations from the local Presbyterian minister that he had had improper relations with a young student while rooming with the student’s family. The improper relations charge was a big deal. A group of people, intending to tar and feather Whitman, headed to where he was staying and demanded that he present himself. The poet hid in an upstairs bedroom as the female head of the house berated the mob and told them to go away. The mob left, and that was that. This story was first published as a pamphlet by Long Island historian Katherine Molinoff. Molinoff interviewed the descendants of the people of the town of Southhold, where Whitman taught school. The story’s detractors say the townspeople of Southold were just angry that Whitman had written a strong anti-slavery editorial in the local newspapers and were out to get him.

The guide and I had a heated debate about Whitman’s sexuality right there in Whitman’s bedroom, but I soon realized that I wasn’t getting anywhere. Raising the white flag of defeat, I gave her the copy of Partisan Review that I was carrying and asked that she place it somewhere on Whitman’s desk as a “token expression” of a view that opposed her own. I’m sure she threw it in the trash as soon as I left the house.

But as Roy Morris writes in his book, Walt Whitman in the Civil War, “It is possible to read too much into Whitman’s same sex kisses—and Whitman hugged and kissed a lot of men, including Oscar Wilde. “Same-sex affection had not yet become eroticized, and overt demonstrations of affection between men—kissing, hugging, stroking, and petting –were commonplace. Behavior that would instantly attract attention today went virtually unnoticed in the mid-nineteenth century.”

But when Whitman met twenty-one-year-old Thomas Sawyer, a soap maker from Massachusetts, a Union soldier who had been injured and was in Washington’s Armory Square Hospital, the story becomes more like Glenn Close’s role in Fatal Attraction. Whitman found his feelings for the young man boiling over and set aside clothes for Sawyer to pick up after his release from the hospital. When Sawyer failed to show up Whitman wrote to him and complained. But Sawyer told a friend that he simply forgot that he had to meet the old man and then wrote Whitman a formal note which seemed to put a distance between the two. The poet then sent a flurry of unanswered letters to Sawyer. “You must not forget me,” he wrote. “We should come together and be true comrades and never be separated in life…my soul can never be completely happy, even in the world to come without you.” Sawyer continued to be silent. Whitman did not give up but came back with: “I do not expect you to return for me the same degree of love I have for you.” Whitman kept sending letters to Sawyer but got no response. “I can’t understand why you have ceased to correspond with me,” Whitman wrote again. The poet then sought out an intermediary but nothing came of it. “Do you wish to shake me off?” Whitman asked, “That I cannot believe!”

Whitman was outside political parties and in many ways, he was antagonistic towards them. Although he tended to approve of socialistic movements in foreign countries, he was quite the opposite when it came to his own country—though he also had some pretty awful things to say about capitalism. He was a poor man but he loved the company of the wealthy. He contained multitudes, after all.

On May 31 in Philadelphia’s City Hall Courtyard, Mayor Jim Kenney and Kelly Lee, Chief Cultural Officer for the City of Philadelphia, opened the grand Whitman at 200 event, which included entertainment and performances by legendary poet/singer Patti Smith and Philadelphia’s own The Bearded Ladies Cabaret. A number of poets, writers and members of the city’s arts and culture communities, including this writer, were also present to read selections from Leaves of Grass and to share in the singing of “Happy Birthday.” Judith Tannenbaum, Artistic Director of Whitman at 200 and Lynne Farrington, Project Director of Whitman at 200, read closing last verses from “Song of Myself.” The event was expertly planned, a masterpiece in many ways because of the numerous Whitman at 200 events throughout the city for weeks leading up to May 31 and then following that date.

What I have discovered is that events related to Whitman tend to attract eccentrics and oddballs—this is not to disparage Whitman’s great poetry—so when an event like Whitman at 200 is organized one can expect surprises, some pleasant, some irksome, but since the poet contains multitudes, almost everyone stands to be offended, surprised or poked in some way.

The Bearded Ladies Cabaret, for instance, staged a mock trial of the poet in their presentation “Contradict This! A birthday funeral for heroes.” This musical skit put the poet on trial for his racist leanings as seen through a 21st-century lens.

The hard biting left of center philosophy of the Bearded Ladies Cabaret is evident to all of those Philadelphians who have followed the group for years, especially at the infamous (but now defunct) Bastille Day street celebration on July 14 where the group presented an absurdist skit on the French Revolution. At the last and final Bastille Day celebration, the cabaret ladies left the topic of the French Revolution for an anti-Trump presentation that was slapstick, absurdist and ridiculous all at once. With Whitman, the cabaret ladies were much more gracious; they seemed to accept the poet’s social justice shortcomings while honoring his cosmic vision and poetic contributions. There were certainly no calls from the ladies to tear down the Whitman statue in South Philadelphia, an amazing fact considering what the Philadelphia Flyers did to the statue of Kate Smith (they removed it from its pedestal and wrapped it in a black burqa body bag) because the great American singer had recorded a few songs, now considered racist, while under contract at Columbia Record.

The Bearded Ladies Cabaret proclaims that “Art can be both intellectual and accessible, entertaining and meaningful, stupid good and just plain stupid. Our shows tackle the politics of gender, identity, and artistic invention with sparkle and wit.” While many people still find The Bearded Ladies to be cutting edge, many do not. I belong to the latter category although I am always hoping that the Cabaret will do something to change my mind. A bearded man in glitter drag was revolutionary in the 1970s but today it is tired and passé. Bearded, gender-hopping men in dresses, moo moos, kilts and even Bermuda shorts can be seen all over Philadelphia. Yes, Virginia, the margins have already been pushed to their limits and now there’s nowhere else to go. One of the original missions of The Bearded Ladies was to push boundaries and give a voice to misfits in the city.

But a misfit in contemporary Philadelphia would include anyone supporting Trump, a gay Republican or someone who objects to the city’s ranking as a Sanctuary City.

It is, unfortunately, assumed in every cultural venue in the city that every intelligent arts patron agrees with the assumption that “democracy is in trouble,” which of course is code for: the present administration in Washington is evil and must be stopped.

In Philadelphia, it matters little where you go, to the ballet, a play opening, poetry reading or art opening, you will inevitably hear something from the stage that reminds the audience that they are living in dark times, a statement that always points to Trump.

And so it was with Whitman at 200, although at least here we can say that the I am large, I contain multitudes branding would, of course, include a love for the “Democracy is in trouble” crowd. Patti Smith’s rousing songs in City Hall courtyard, ostensibly in honor of Whitman, became almost entirely political in the end. Smith, raising her fist, led the crowd in a chant, “People have the power, people have the power, people have the power!” Suddenly the name Walt Whitman had become synonymous with a call for revolution.

But “People have the power” means what, exactly? That “the people” will put Trump in office in 2020? What we know for certain is that Patti Smith assumed that all Whitman lovers were Trump haters despite the fact that Whitman hated no one and he refused to take sides when it came to politics.

Whitman was anything but an ideologue; political orthodoxy, right or left, was anathema to him. Happily, the vast majority of presenters in City Hall Courtyard kept the focus on Whitman by not adding anything to the Whitman poem they were supposed to read. A couple of presenters, however, did preach on some social justice issue and, like Patti Smith, seemed to infer that all who loved Whitman hated Trump—well, you know the mantra by now.

As for Whitman, he gave a number of Lincoln lectures in Philadelphia and Boston after President Lincoln’s assassination. The Civil War found him working for a number of years as a volunteer nurse in the hospitals of Washington where he looked after dying and wounded Union and Confederate soldiers. He favored the Union but he would not take sides when it came to caring for the injured and the dying. He criticized visitors who would come to the Washington hospitals who chose only attractive soldiers for their love. “Some hospital visitors, especially the women,” he wrote, “pick out the handsomest looking soldiers, or have a few pets. Be careful,” Whitman warned, “not to ignore any patient.”

He opposed capital punishment and for a time was an advocate of the temperance movement, writing a novel, Franklin Evans; or The Inebriate. A Tale of the Times. The book was published in 1842 as a small novel and its author listed as Walter Whitman. The story was a sensationalistic screed against the evils of alcohol. Walt later disavowed the temperance movement and had nothing but harsh criticism for the largely feminist support for prohibition.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member