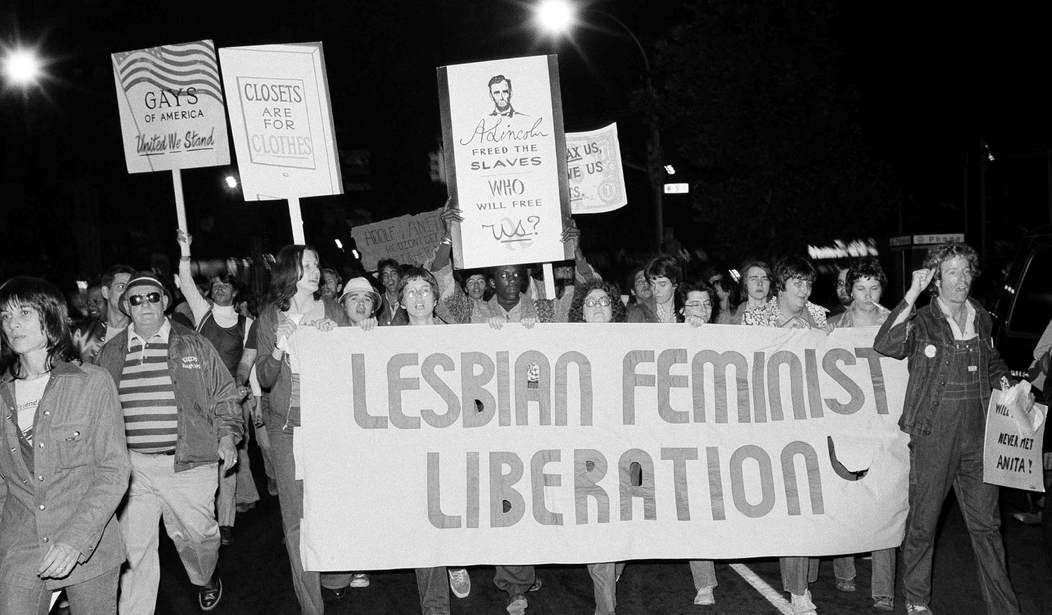

When I worked in a hospital in the late 1970s, I was sitting with several surgeons in the break room when I heard muffled grunts of disapproval. The bone of contention seemed to be the front page story in The New York Times. The story concerned a massive Gay Rights march down New York’s Sixth Avenue. Most in the break room read the newspapers without comment, but one urologist shook his head and said: “These protests are a fad, a phase!”

I heard the word “phase” and told the urologist: “This is not a fad but the beginning of something really big. Buckle your seat belt!”

The idea of gay marriage in the 1970s was so remote you couldn’t even find references to it in published (gay) science fiction novels. In early gay liberation circles, men who had long-term partners were regarded with suspicion if they said that they were monogamous. The 1970s politically correct way of thinking for activists was to equate romantic jealousy and monogamous long-term relationships with wanting to “own” and possess a partner. Wanting to “own” someone’s body and soul was seen as one of the negative effects of growing up in a patriarchal, capitalist society. Many activists criticized heterosexual marriage as the spawn of capitalism with its idea of spousal “ownership.”

Contempt for homosexuals was everywhere in those days. Even in countercultural Boston and Cambridge where I lived for a while, I used to hear bearded, socialist hippie “revolutionaries” spout the word “fag” with abandon when they were not, like Jerry Rubin, stealing books. They would talk about tearing down the capitol building and the military industrial complex while at the same time sounding like John Wayne or Art Linkletter when it came to “fags.”

When the idea of gay marriage first made small strides in the early 1980s, it was a fringe idea at best. Most self-respecting gay people valued their personal sexual freedom and saw the insular married world of Ozzie and Harriet as a form of relationship slavery. For many the idea that you could only have sex with one person for the rest of your life seemed like a special kind of hell. But like the acceleration of a small faucet drip into a robust, gushing stream, the idea of same sex marriage began to catch on. The first reports of marriages came from gay-identified churches like the Metropolitan Community Church, the Unitarian Church, and the United Church of Christ. In the Jewish world, you’d hear of a liberal rabbi uniting two men or two women in a home ceremony or in a gay synagogue. Reports of renegade Catholic or Anglican priests “marrying” two men or two women would surface a little later, but they were not common. Generally, these union ceremonies were still regarded as freak occurrences in a community that still saw marriage as a heterosexual institution.

“We don’t want to be like straight people with their cottages and white picket fences,” was a common refrain then.

As a 21-year-old I was lectured to by my gay elders. “Gay relationships don’t last,” they said. “There’s no Prince Charming. It’s better that you know now.” I was devastated. Here I was just getting used to my “gay training wheels” when I was being told that sexual love only lasts a season or two.

While gay relationships — the in love lusty variety, anyway — may not last, gay friendships do. I’ve never had a partnership last more than seven years. Perhaps this says something about me (do I need an analyst’s couch?), or perhaps it says something about the nature of the sexual chemistry between two men.

My best friends today are former partners who have become close platonic soul buddies, proof perhaps that Christopher Hitchens, who was bisexual in his youth, was on the money when he observed: “Homosexuality is for the young.”

In those early days, MCC couples who wished to tie the knot had a so called Holy Union ceremony. There were no legal ramifications to this ceremonial blessing. I attended one Holy Union service in the mid-1980s when a Navy lieutenant “married” his sailor boyfriend in the Joseph Priestly chapel at Center City’s First Unitarian Church. The reception was a snapshot of the traditional straight wedding: a sit-down meal, champagne toasts, dancing, two men in tuxedos, a tall white wedding cake topped with two grooms plus an end show where the two grooms rubbed cake in each other’s faces. Attending this Navy wedding made me realize that the old activist line concerning marriage was fading. However, the MCC minister at that time was still warning male couples who wanted a Holy Union that they first needed to take a serious look into making room “for the occasional other,” meaning, of course, an “on call” boyfriend who would rescue you once your marriage got stale. In retrospect, this somehow reminds me of that old Boy Scout (RIP) motto: “Be Prepared.”

The assumed truth here is that all marriages, homosexual and heterosexual, eventually go flat like seltzer water, although unlike a man and a woman, there’s no reason why two men, sans children, would feel obligated to “stick it out” until “death do us part.”

But now that same sex marriage is on an equal legal footing with heterosexual marriage, effectively relegating those old “marriage is bad” activists to the dinosaur bin, the “teaching” in the gay and lesbian community has changed. Many younger gay activists today have forgotten what the movement used to preach when it came to monogamy and relationships — and some even become uncomfortable when reminded of this fact.

I experienced this first-hand several years ago soon after the Supreme Court’s ruling on same sex marriage. At a party where some of the guests were chatting about marriage equality, I segued into a history lesson, albeit lighthearted, but my words were not received well. The host lashed out: “Nobody wants to hear that. That’s such a downer,” and told me to leave.

And so I retrieved my sports jacket from the back of a dining room chair, and walked out.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member