There was something in the air in Hollywood in 1966. The three television series most associated with 1960s network television, thanks to their endless reruns in syndication throughout the following decade, premiered that year. First ABC’s POW! ZAP! pop-art-themed Batman, starring Adam West and Burt Ward as the campy crusaders debuted in January, giving the venerable comic book a shot in the arm in sales that kept the franchise alive long enough to lead to Warner Brothers’ movie franchise beginning in 1989 and continuing to this day. That fall, they would be joined by NBC’s The Monkees, Columbia television’s “pre-fab four,” inspired by director Richard Lester’s Beatles movies, and another NBC series with the longest legs of all, Star Trek.

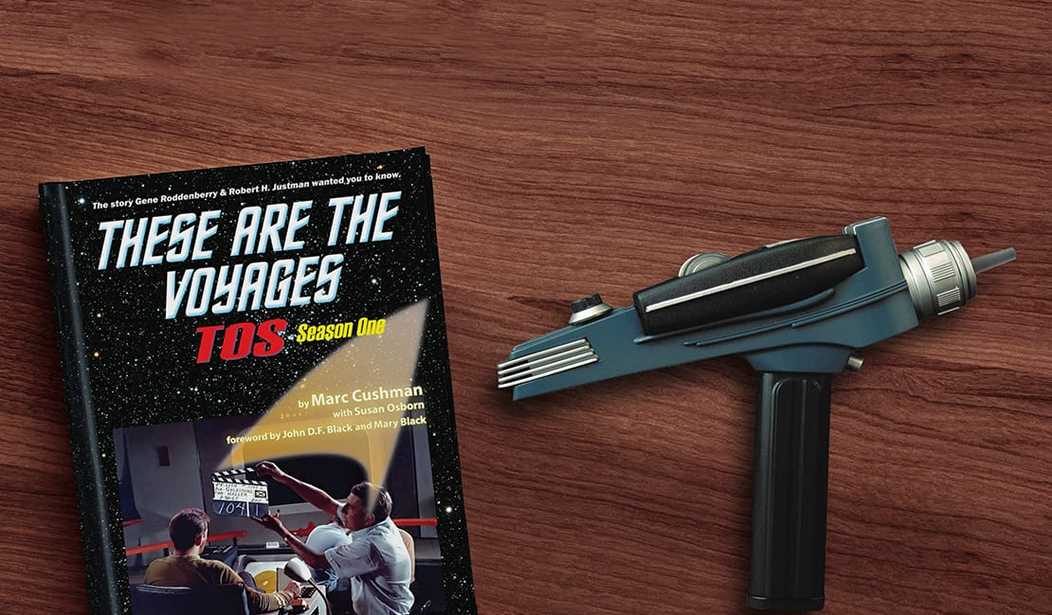

Star Trek, as Marc Cushman writes in the first volume of These Are The Voyages, his trilogy exploring the tumultuous production history of each of the series’ three seasons, whose release was authorized by Star Trek producers Gene Roddenberry and Robert Justman, made it on the air in spite of itself. Each book documents the overarching questions most fans have about each season of Star Trek. For season one, Cushman explores how a show like Star Trek was able to get on the air, in the culturally conservative (though politically liberal) media overculture of the 1960s.

In his history of season two, Cushman looks at how Gene L. Coon, what we would now call that season’s chief “showrunner,” oversaw the crafting of some of Star Trek’s most memorable episodes, but why he left the show midseason, arguably at the show’s peak. The second season edition of These Are The Voyages also looks at the letter campaign that helped Star Trek get renewed by NBC, and how a surprising intervention kept actress Nichelle Nichols on the show as Lt. Uhura. The third season’s edition of These Are The Voyages explores why NBC buried the show at a 10:00 p.m. Friday night time-slot, long a television graveyard in the era before first VCRs and then TiVo, and why the show’s writing declined so precipitously.

If you were as fanatical about Star Trek as I was during the 1970s, when it first began its endless cycle of reruns, some of the deep dive to follow will seem old hat. But there were several areas in which Cushman’s books brought new insights into easily the most written about show in the history of American television. So let’s take each of these books season by season, beginning this week with Season One and…

Leaving Drydock: Getting Star Trek on the Air.

Gene Roddenberry (1921-1991) was a religious agnostic and left-leaning Texan who became a WWII Army Air Force B-17 pilot, then an LA policeman who wrote numerous scripts for the burgeoning television industry in the 1950s. Eventually, he graduated to producing his own TV show in 1963, The Lieutenant, purchased by NBC and built around Gary Lockwood, the future guest star of Star Trek‘s second pilot, and the co-star of another landmark 1960s science fiction achievement, Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

The Lieutenant was for the most part a formulaic “military procedural” about life at Camp Pendleton, and featured numerous future Star Trek guest stars and cast members. However, Roddenberry, as was his wont, eventually decided to push the envelope, and put into production an episode on racism in the Marines called “To Set It Right,” with guest stars Dennis Hopper, future Star Trek regular Nichelle Nichols and future Trek guest star Don Marshall. The episode lost the support of the Marines, and the good will of NBC. As Roddenberry later recounted, “My problem was not the Marine Corps; it was NBC, who turned down the show flat…. There was only one thing I could do, I went to the NAACP and they lowered the boom on NBC.”

As Cushman writes, this did not endear himself with NBC’s executive suit. “Roddenberry had won the battle … but lost the war. Despite satisfactory ratings, The Lieutenant was cancelled.” And NBC’s executives would not forget being hung out to dry by one of their product suppliers.

Even before The Lieutenant’s only season of production was complete, Roddenberry began crafting a television show he called Star Trek. He had somehow stumbled into the perfect format for an hour-long network television series. While he admired shows such as Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone and its recombinant network rival The Outer Limits for their ability to comment on American society through the metaphors of science fiction and horror, these were anthology shows, introducing a new cast each week. He knew the most successful network series were those with a recurring cast, such the many westerns that aired during the 1950s and ‘60s, such as the long-running Bonanza and Gunsmoke. Viewers treated these archetypal characters almost as their own family members, which in turn encouraged them to tune in each week.

Given the networks’ love of westerns in the 1960s, it’s no coincidence that Roddenberry’s first pitch to the networks used the phrase “Wagon Train to the stars” as a metaphor to describe the show. (As Cushman writes, veteran western and science fiction writer Samuel Peeples actually coined that phrase, the first of many bits of Star Trek lore that Roddenberry would eventually co-opt and take credit for.)

It’s also no coincidence that the show’s second in command was written by Roddenberry as “a mysterious female, slim and dark, expressionless, cool, one of those women who will always look the same between years 20 and 50.” As Cushman deadpans, “To be more specific: actress Majel Barrett, Roddenberry’s lover.” (Roddenberry was also having a tryst with Nichelle Nichols; she would find her way into Star Trek‘s regular cast as well.) While the pointed-eared alien Mr. Spock was also present, he was much more in the background in Roddenberry’s first draft of Star Trek.

Titled “Star Trek Is,” and dated March 11, 1964, this would be the first draft of the series’ “bible,” issued to prospective Hollywood writers to explain to them the basics of the show’s characters, and how its futuristic technology worked. Roddenberry wanted a giant spacecraft, so that he could plausibly bring in guest stars to play a crewman of the week whose character could be explored. The show needed to be set far enough in the future to make faster than light travel plausible, and unlike NASA’s cumbersome 1960s space launches, to make the technology of the spaceship almost as seamless as putting the key in an automobile and going for a Sunday drive. The transporter, which would become Star Trek’s signature effect and best-known catchphrase (“Beam me up, Scotty!”) Roddenberry arrived at shortly afterwards, as a way to avoid requiring expensive (and likely phony looking) special effects showing a model of his giant spacecraft landing and taking off, and crewmen walking out onto the planet of the week. He named the ship the Enterprise after the WWII aircraft carrier, and used plenty of navy lingo to keep confusing space-age technical jargon to a minimum.

As Cushman writes in the first season’s edition of These Are The Voyages, CBS fielded Desilu’s first pitch for Star Trek, because “the Tiffany network” broadcast Desilu studio owner Lucille Ball’s The Lucy Show. However, as a result of Roddenberry’s poor skills as a pitchman, and the fact that CBS was already developing its own sci-fi series, Lost In Space, it was a strike out. Next up was a meeting with NBC, which, as Cushman writes, already had bad blood with Roddenberry, thanks to his efforts at shaming the network over The Lieutenant. It was Desilu executive Herb Solow who made the sale, but NBC would always be weary of the product they had purchased, and the producer running it.

Roddenberry knew he needed scripts, lots of them, and while he wanted the cachet of legendary science fiction writers associated with the show, many of them didn’t have a background in the rigorous cookie-cutter structure that episodic television dictates, with a teaser, four acts each ending with a climax, and an “all’s well” wrap-up segment, plus room for plenty of commercials in-between each act to pay the bills. Plus, at the start of the series, with only its two pilot episodes and its writers’ guide to review, the writers would have little knowledge of the relationships of the characters’ interrelationships, and their speaking patterns.

In his first volume, Cushman explores the conflict between the show’s first story editor, John D.F. Black, and Roddenberry. Roddenberry set the trend for Star Trek: while the production team would hire outside writers to bring in new premises and characters, Roddenberry would heavily rewrite each episode to ensure that the characters he created behaved and spoke in a consistent manner. His associate producer, Robert Justman, would review each script with an eye on the budget, frequently eliminating expensive and unnecessary props or special effects.

This approach angered Black, who wanted to bring in great writers and had promised them that they wouldn’t be rewritten by Roddenberry, someone that Black understandably did not believe was in the same class with the writers he was recruiting. Only four months into his relationship with Star Trek, and having written the show’s now legendary “Space, the Final Frontier” narration for the show’s opening credits (where of course, the title of Cushman’s books is derived from), and the episode “The Naked Time,” Black departed the series. As Cushman writes:

Black had grown more disenchanted each week, believing Roddenberry’s rewrites were damaging to many of the scripts. Black admired writers such as Jerry Sohl, Richard Matheson, George Clayton Johnson, and Robert Bloch. He felt Roddenberry displayed less talent than these men and should not be changing their words. Examination of the various drafts of the scripts for these episodes gives indication that some changes were for the better, some perhaps not, but, generally, it was more so a case of personal taste. Regardless, Black had other issues beyond the caliber of the rewriting. He later said, “I realized that there was no way that I could stay there. I gave the writers my word that they would get to do all their changes first, before we ever got to it. Because GR told me I could say that. And then he changed everybody’s scripts. There wasn’t a script he didn’t screw with — mine, Bob’s, Richard’s, George’s, every script. And every time he did it, it became more and more clear to me that he was making my word bad. Every time I said to a writer, ‘Hey, guy, you get to do it; this is a show for a writer; this is a writer’s show,’ he made my word bad. I was dealing with great writers, too — Harlan Ellison, Ted Sturgeon, Richard Matheson, George C. Johnson, Bob Bloch. It made no sense.”

Black leaving the series created an opening for a new line producer: Gene L. Coon, then 42, coming off of the hit CBS TV series The Wild, Wild West, produced by Fred Freiberger, whose name would also come to be associated with Star Trek. If Freiberger is seen (rightly and wrongly) as the man who killed Star Trek, it was Coon who made it a legend. Coon wrote sparkling dialog that cemented Kirk’s friendships with Spock and Dr. McCoy, and also the “frenemies” relationship between the latter two characters. Coon also transformed Roddenberry’s show from a somewhat ponderous melodrama in space to a quicker-paced action adventure series, as Cushman notes in his chapter on the first season episode, “Arena:”

Under Gene Coon’s guidance, Star Trek was rapidly becoming faster-paced. Coon felt that Star Trek could remain adult and, at the same time, be a bit more fun. Care, however, was still taken to keep the series believable. To this end, it was agreed among the creative staff that the Gorn would not speak English. Instead, to honor a suggestion made by Roddenberry, a translator device was introduced to allow the two combatants to communicate.

“Arena” was the first episode to refer to the Earth space alliance as the “Federation,” a contribution from Coon. The script for the upcoming “A Taste of Armageddon,” having been around for a while and going through various revisions by Coon, would be more specific, identifying the alliance as The United Federation of Planets. “Arena” was also the episode which introduced the photon torpedoes, another Gene Coon invention.

To borrow a phrase from David Gerrold’s 1973 book, The World of Star Trek, Coon transformed the series from “Kirk makes a decision,” to “Kirk takes action” (frequently involving phasers, fist-fights, lovemaking, or some combination thereof). Coon also created Star Trek’s most popular baddies, The Klingons, during the first season. It was all going well under his stewardship, until it wasn’t. We’ll look at Season Two, the remarkable intervention that saved Nichelle Nichols from quitting Star Trek, and how it all started to go wrong for the series, next week.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member