Note: Most Thursdays, I take readers on a deep dive into a topic I hope you'll find interesting, important, or at least amusing. These essays are made possible by — and are exclusive to — our VIP supporters. If you'd like to join us, take advantage of our 60% off promotion.

"A capitalist society does not want more than two cheers for itself. Indeed, it regards any impulse to give three cheers for any social, economic, or political system as expressing a dangerous — because it is misplaced — enthusiasm." —Irving Kristol, in the preface to Two Cheers for Capitalism

It is unseemly, untimely, unjustifiable, distasteful, and surely flat-out wrong to offer even one cheer for colonialism.

So here I go.

Representatives from 12 European nations, plus the U.S. and the Ottoman Empire, gathered in Berlin on Nov. 15, 1884, to impose order on the 15-year "scramble for Africa." Sponsored by Imperial German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck — who was initially opposed to Germany taking foreign colonies but acquiesced to public pressure, geopolitical realities, and Kaiser Wilhelm II's ego — the Berliner Westafrikakonferenz sat for three months to carve up the continent between them, regulate its trade, and avoid a general European war in the scramble. Africans had no say in any of this, of course.

Europe's machine guns, steamboats, rapid communications, and nationalistic ambitions proved irresistible — and yet despite all that power and ego, every one of those empires crumbled after less than a century. A few decades after that, colonizers became the colonized.

Following WWII, Britain and France — the only remaining European colonial powers (a definition that excludes the USSR, but stick a pin in that thought) — could not hold their possessions. Two world wars in rapid succession left them militarily, financially, and morally exhausted. And yet the lines drawn in Berlin in 1885 by men wearing silly helmets are almost exactly the same ones you'll find on any modern map.

And Another Thing: The U.S. was an observer to the Westafrikakonferenz, not a signatory. Anti-colonialism is baked into our cultural DNA, but we did have global economic interests to attend to.

During decolonization in the 1950s and '60s, all involved decided it would be best for everyone to respect the existing borders. Since the alternative was likely a pan-African war, they were probably right.

But that doesn't mean things have been easy since.

Those borders were often deadly nonsense, particularly in West Africa. There, populations, cultures, and economic ties tend to run east to west, but the "countries" forged by foreigners mostly ran north, up from the ports and coastal cities taken by the colonizers.

The French might take a couple of towns on one part of the coast, the Brits the next town over. From there, colonizers from both nations would go inland in pursuit of further riches. So coastal cities had their economic ties severed, and peoples that didn't go together got smooshed up in new colonial territories.

If you're wondering where I get to the part where you let out a single cheer, please stick with me a little longer.

Don't even get me started on the slave trade. Yeah, the Arabs and Turks started it, but it took Europeans to industrialize it. It took a long and concerted effort by two Euro-adjacent peoples — the English and the Americans — to end the slave trade.

But back to European colonization of Africa, which, aside from some coastal possessions, only really got going in the mid-1800s, barely lasted a century, and yet left deep psychic scars on both continents.

This might be a bit of a tangent, but European colonization — and the stupid maps they generated — was hardly limited to Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

Here's that thought I asked you to stick a pin in.

The Soviet Union made virtual protectorates out of the nations of Central Europe after World War II, just one kind of colonialism among several.

Stalin didn't erase the existing borders, but ordered populations moved around to fit them. He cleared the Germans from Poland and Czechoslovakia, and forced the Poles out of the Soviet republics of Belarus and Ukraine. You should condemn his methods (I certainly do), but you must admit that those countries have been mostly free of ethnic strife with one another ever since.

I'd be remiss if I didn't also mention that it's a centuries-old Russian practice to move ethnic-Russian settlers into conquered nations (the Baltics, Moldova, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, etc.) or weaker neighbors with the goal of inflaming ethnic strife that Moscow could then exploit. That single cheer really is difficult to muster sometimes.

For a notoriously awful example of colonialism, it's difficult to do worse than King Leopold II of Belgium in Central Africa. The Congo Free State really wasn't a colony at all to start off — it was Leopold's personal estate. He ran it on cruelty, brutality, and slave labor to extract mineral wealth. The Force Publique (Leopold’s private army) used mutilation (cutting off hands), hostage-taking, and village burnings as punishment for not meeting his strict rubber quotas.

Leopold's treatment of the indigenous people was enough to shock even 19th-century European sensibilities. In 1908, his own government took away Leopold's estate and established the government-run Belgian Congo. If the Belgian Congo wasn't exactly nicely run — something along the lines of Apartheid South Africa — at least it brought a stop to Leopold's mass murders, amputations, and punitive expeditions.

Since 1994, what's happening in the Democratic Republic of the Congo would look familiar to Leopold's thugs. Today, foreigners (albeit African foreigners) and local militias use brutal means to extract the country's mineral wealth, including mass murder and amputation as needed. Was post-Leopold Belgian rule really that much worse than what eventually followed? I really couldn't say for sure, but maybe it's time we stopped pretending the issue is settled.

Nothing to cheer for, to be sure, but neither is the Congo's post-colonial history.

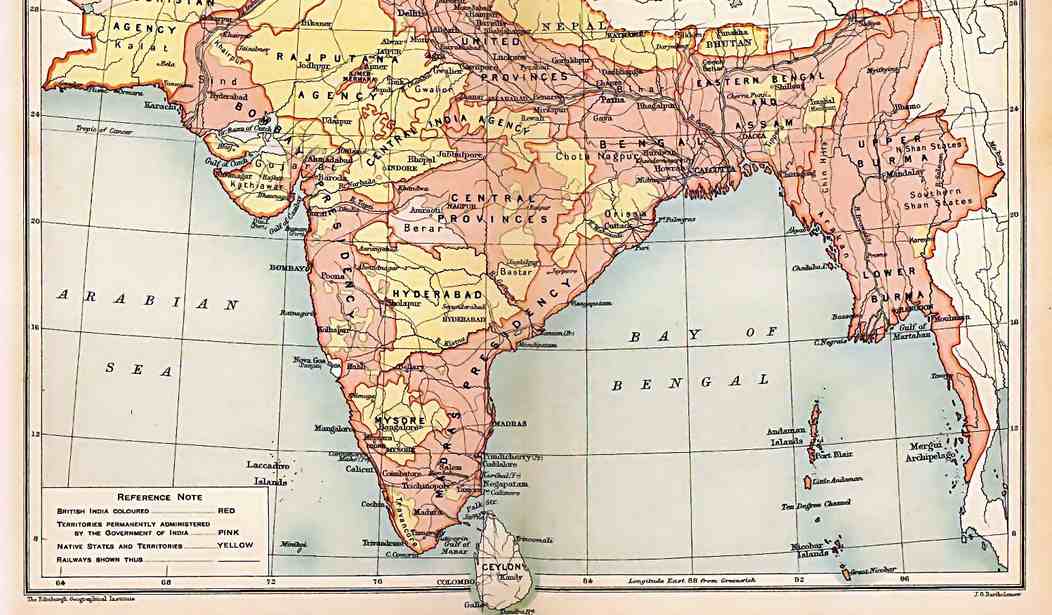

No discussion of colonialism is complete without at least a brief look at the British Empire's crown jewel: the Raj, the 1858 culmination of centuries of increasing British control over the entire Indian subcontinent.

Many years ago, in a book otherwise long since forgotten, I read that per capita GDP increased so little for the people of India during British rule that it was hardly worth mentioning. The author meant to condemn the British for stealing all that Indian wealth. But I wanted to grab the author by the lapels and shout, "WEALTH HARDLY INCREASED ANYWHERE FOR ANYBODY BEFORE THE BRITISH AND THE DUTCH INVENTED CAPITALISM, YOU NINNY!" So I yelled at the book, instead.

I shout at my books sometimes. Don't you?

So how did a puny number of Brits control the 300 million (at the time) people of India?

Hilaire Belloc quipped in 1898, "Whatever happens, we have got the Maxim gun, and they have not," which is true enough. But the liberal application of overwhelming force tells only part of the story.

For starters, Britain only ruled India directly where absolutely necessary, or most profitable. Direct British rule covered about 60% of the Raj, while the local "princely states" — more than 500 of them — self-governed the remainder. In acquiescence to British superiority, of course.

The British deliberately cultivated an aura of unshakable authority, with an emphasis on making it appear effortless. That aura was embedded in doctrine, in officer training, in daily conduct, and even in how officers of the Raj dressed. Ever wondered why the Brits wore such fancy uniforms, even in the Indian heat? Now you know. And even in summer, the Brits never let them see them sweat, so to speak.

That image of British invincibility — already brittle with fatigue after World War I — was shattered by the Japanese with the sinking of the battlecruiser HMS Repulse off Malaya in December 1941, and the fall of British Singapore in 1942. It was previously unthinkable that 36,000 Japanese could kill or wound 5,000 British, Indian, and Commonwealth soldiers, while suffering fewer than 2,000 casualties of their own. But the real shocker was that another 80,000 British and British-led troops simply surrendered.

To Asians.

The Empire would stagger on for another two decades or so, but Singapore was the death blow, the Wizard revealed as just another mortal man.

And Another Thing: While it's beyond the scope of this essay to really get into, Lord Louis Mountbatten gravely rushed the British exit from India in 1947 — among many other mistakes — leading directly to at least one million deaths in the chaos, and endless Indo-Pakistani conflict over Kashmir. Now, where did I leave that one cheer?

In the end, though, whether the colonizer spoke English, French, German, Japanese, or Russian, the end of empire inevitably followed the moral hazard of relying on superior firepower instead of legitimate authority derived from the consent of the colonized.

Although there's no need to hedge on this one: Most everybody in Sudan (both Sudans) would be happier if the Brits still ran the place, and oodles of them would still be alive.

Don't get me wrong — I'm not advocating anybody in the West get back into the business of colonizing anybody.

The Europeans no longer have the élan for it, and besides, things have changed a lot in the last couple of centuries. When Napoleon took his little army gallivanting unchecked through Egypt in 1798, there were barely more than four million (almost entirely unarmed) Egyptians. That's compared to about 29 million Frenchmen mustering one of the most-feared armies in all of Europe.

Today, there are about 66 million French citizens, and roughly 6 million of those are Muslim — and certainly not very enthusiastic Frenchmen. Modern Egypt teems with 120 million people, and if AK-47s aren't already plentiful, you can bet they'd get that way shortly after a modern Napoleon showed up. Or an Evelyn Baring, for that matter, Britain's first Consul-General over Egypt, eight decades after Napoleon quit.

As for the U.S., we are temperamentally unsuited to the task.

We went into the Philippines with enough enthusiasm in 1898 during our war with Spain — a war that made us an imperial power almost by accident. The war was on purpose, of course, but it isn't clear that anyone in Washington thought Spanish resistance in Cuba, the Philippines, and elsewhere would collapse so quickly or completely. Just like that, we had ourselves a little empire.

Before long, we couldn't wait to get rid of it.

FDR signed the Tydings–McDuffie Act in 1934, setting a Philippine independence date of July 4, 1946. That was thought to be enough time for the Filipinos to establish a well-run national government of their own, and not even World War II and three years of brutal Japanese occupation could budge us from lowering our flag as soon as we were ready.

And Cuba?

We took charge the way a distracted dad does when mom is out of town for the weekend. We built some roads, drained the fever swamps, wrote them a nifty new constitution, and then went back to tinkering with our old sports car in the garage. Direct rule lasted all of four years, although we did intervene from time to time, before pretty much turning the place over to the Mafia. And then to Castro.

Silly us.

I'm not saying we're always nice guys, because we aren't. The U.S. has rarely been afraid to use gunboat diplomacy (or worse) when it suited our purposes. We prefer, however, to get in, get out, and get back to business. Even though they were, historically speaking, low-casualty wars, our misadventures in Iraq and Afghanistan still sting because we went against our cultural grain in pursuit of impossible goals.

I mean, the Russians will endure global sanctions and more than a million casualties in a years-long pursuit of imperial conquest over Ukraine — but that's just not our style.

What is in style today is what I think of as postmodern reverse colonization.

"Postmodern," because the colonizers represent a culture in many ways cheerfully stuck in the 7th century — assuming "cheer" is an adjective anyone might associate with militant Islam. "Reverse," because the colonizers come from countries much poorer and less powerful than the colonized.

It's a five-step process, and from Manchester to Minneapolis, here is how postmodern reverse colonization is done:

- Migration, often at the behest of the local population or their elites.

- Non-assimilation.

- Formation of ethno-religious political blocs.

- Street violence/mob tactics/mass rape as power tests.

- Demographic tipping points.

You can look at almost any major city in Western Europe and see the completion of the third step coming into play — and in this country, in Minneapolis and Dearborn. There are places in Britain, France, Germany, and elsewhere already undergoing the final step.

For all the senseless slaughter in the Congo, or France's vicious Algerian War decades later, Europeans only rarely established demographic superiority. Postmodern reverse colonization might well prove permanent in ways 19th-century colonialism couldn't.

It's enough in the end to make you give out a cheer for the French colonists in Algeria 60 years ago, and how much more French France might be today had the French remained in Algeria and kept the postmodern reverse colonizers at bay.

Europe's elites went all "Three cheers for colonialism!" two centuries ago, and left scars across the globe that have yet to fully fade. Now they've gone all "Three cheers for Muslim colonialism!" and risk losing a continent.

Surely, there must be some middle ground worth a cheer or two.

Last Thursday: Pride Goeth Before the Fall of Europe