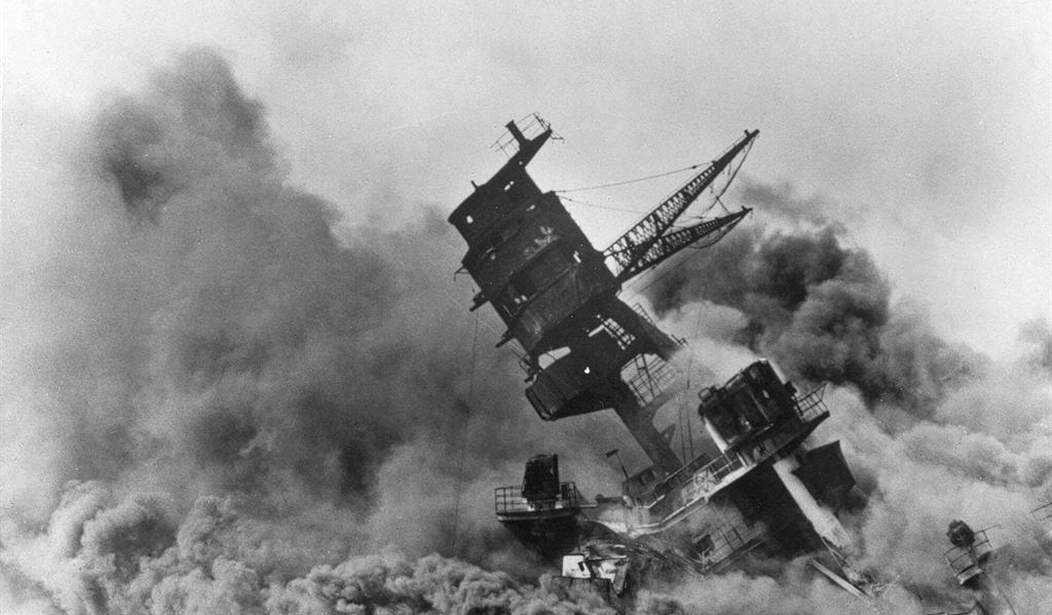

One sleepy Sunday morning, nearly 200 Imperial Japanese dive bombers, torpedo bombers, and Zero fighters appeared as out of nowhere in the skies over Hawaii.

Their target: The American Pacific fleet sitting at anchor at Pearl Harbor, once thought virtually impervious to attack.

Japan achieved complete surprise, despite having been “caught” by an early American radar installation. The operators assumed the blips were an expected arrival of American B-17 bombers from California.

Recommended: ‘Jaw-Dropping’ Gains for GOP in Florida as COVID Refugees Register RED

The Japanese pilots — the best-trained and most experienced naval aviators in the world at the time — had orders to seek out and destroy America’s aircraft carriers. By happenstance, our carriers were out delivering planes to American’s outer defenses further west in the Pacific. Japanese-American tensions had come to a height, and American military planners had not discounted Japan initiating hostilities with a sneak attack as they’d done to Russia in 1904.

We just never thought they would — could — strike as close to home as Pearl Harbor.

But they did. Twice.

A second wave of an additional 200 or so fighters and bombers hit more targets at Pearl and Hickham Field.

The chaos in the harbor was indescribable. The chaos on the ground was arguably even worse.

The Japanese striking force — their Kido Butai of six aircraft carriers and assorted support ships, operating in perfect unity — could have done more damage. But Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, unable to locate the missing American aircraft carriers, decided that discretion was the better part of valor and withdrew without launching the planned third attack wave.

Yamamoto could call it a good day, having sunk four American battleships, damaged the other four, and also damaged three cruisers, three destroyers, destroyed or damaged almost 350 of our planes, and killed or wounded more than 3,400 Americans.

His losses were a pittance, with around 100 planes damaged or destroyed, and 64 KIA.

Japan didn’t muster Kido Butai lightly or out of mere spite just to take on the world’s industrial powerhouse in a fruitless war.

No, Japan meant business. Its imperial project included conquering all the best parts of China, pretty much everything in the Western Pacific, and replacing the British Raj in India, too.

It was an empire built on vicious conquest and cruelties surpassed in modern warfare only by their Nazi allies in Europe.

To continue and expand its “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” Japan was hungry for the oil President Roosevelt would no longer allow them to buy from the U.S. Yet all the oil they would ever need was right there for the taking in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia).

But the U.S. Commonwealth of the Philippines stood in the way.

To get to the oil then, Japan would have to come through us. Tokyo had hoped for — and Yamamoto promised to deliver — a first strike at Pearl so severe that America would settle a short war on terms favorable to Japan.

It didn’t quite work out that way, with Japan signing an unconditional surrender document in 1945 on the deck of the USS Missouri — a mighty battleship that didn’t even exist on Dec. 7, 1941 — right there in Tokyo Bay.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was, in short, one just small element, ruthlessly executed, in Imperial Japan’s decade-long quest to conquer, rule, and exploit a quarter of the Earth.

Recommended: Get Away From It All in Antarctica, Get COVID Anyway

On another date that will live in infamy — although not for the reasons hoped for by those seeking to exploit it for political gain — something quite less happened.

A few deluded souls, by most accounts encouraged and abetted by agents of the United States federal government, split off from the ongoing peaceful protest and indulged in a minor and short-lived riot.

Anyone daring to compare Dec. 7 to that other date is a terrible person engaging in the most capricious and destructive politicking imaginable short of an actual insurrection.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member