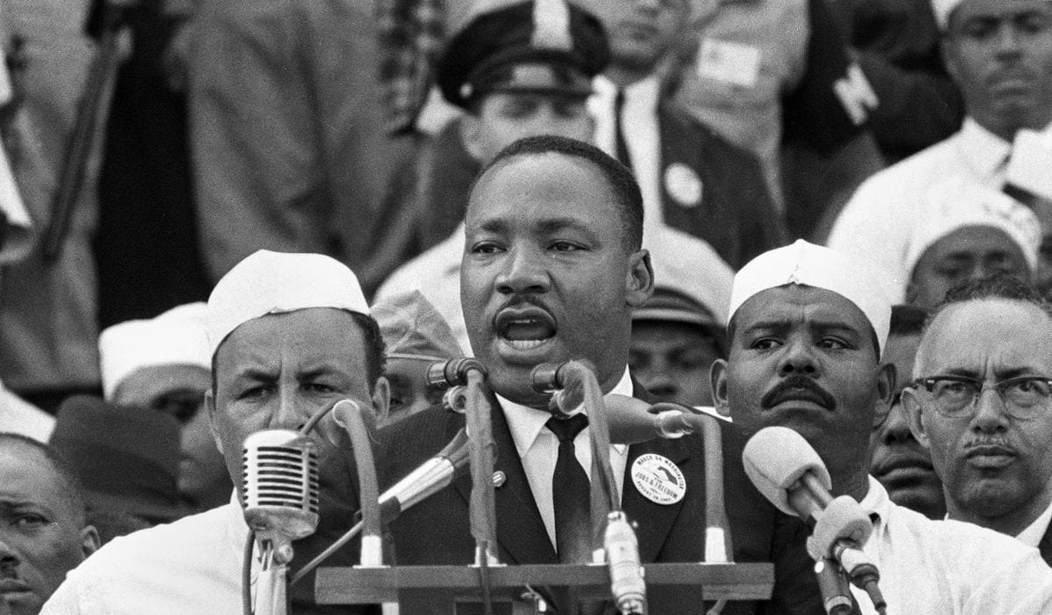

In his famous speech offered before the Lincoln Memorial in 1963, Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. spoke of a powerful faith. With it, he claimed “we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope.”

King’s legend has been similarly crafted, hewn from the mountain of truth into an image serving those who carved it. The real Martin Luther King, like most public figures, remains greatly obscured from history. Was he the devout Christian minster who preached forgiveness and reconciliation? Or was he a radical community organizer who would march today alongside Black Lives Matter?

Today’s racial agitators resent the “appropriation” of King by mainstream America. Writing for Dissent, author Osagyefo Uhuru Sekou raises the objection:

… pundits of all persuasions have invoked his name to browbeat younger activists and their tactics. Such is the case with Movement for Black Lives (M4BL), commonly known as Black Lives Matter (BLM)…

… The real King stands in stark contrast to our current pop image of him. An avowed democratic socialist who called for the redistribution of wealth in several speeches and sermons, Martin Luther King was loathed in many quarters. He was stalked by the FBI, undermined by the Attorney General Robert Kennedy, and labeled “the most dangerous man” alive and a “notorious liar” by J. Edgar Hoover. King’s own board of directors at Southern Christian Leadership Conference censored him for his opposition to the Vietnam War.

Sekou cites historical polling data which indicate King peaked in popularity in 1964-65, the zenith of the civil rights movement during which key legislation was passed. After that, King’s popularity plummeted as his rhetoric and tactics turned more radical. Yet, as Sekou notes:

Our contemporary version of King is strikingly different. A 1999 Gallup study determined that Martin Luther King was one of the most admired figures of the twentieth century, second only to Mother Theresa, and in 2011 Gallup rated his favorability in the United States at 94 percent. With a national monument and federal holiday to boot, King’s status as a national hero is by now indisputable.

A worthy question which Sekou fails to address is: Why? Why does America revere Martin Luther King today? Did we change? Did 94 percent of Americans grow to appreciate democratic socialism? Or is the object of our reverence more specific than the man?

Whoever King really was, whatever he sincerely believed, the image of King worth celebrating was presented in that 1963 speech. We aspire toward a world where children “will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” That vision of racial reconciliation, of judgment according to merit, speaks to each and every human being. It’s something we can and should get behind. It evokes the American spirit, a point emphasized when King cited the Declaration of Independence. Ninety-four percent of Americans came to favor King because they associate him with that dream, not because they support whatever radicalism he later embraced.

King’s dream remains worthy, but can only be achieved by people committed to liberty. Peace and harmony will not manifest through coercion, but through benevolent grace. King’s frustration in his latter days may have driven him to forget that. Even so, his former grace must be credited for securing his greatest victories, and carving his legend from history.

Consider again these words from that 1963 speech:

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

These sentiments built upon an earlier warning against “distrust of all white people.” King called for true reconciliation, for the elimination of color as a metric of worth.

Those who lay claim to King’s legacy today, and seek to align it with the radicalism of Black Lives Matter, preach a wholly different message. Rather than minimize that which divides us, today’s racial agitators actively inflate it. From Sekou:

At the center of the M4BL coalition sits the national Black Lives Matter network, co-created by two queer black women, Patrisse Khan-Cullors and Alicia Garza, and their sister-comrade, Opal Tometi. The movement they have helped incubate focuses on organizing the most marginalized: domestic workers, immigrants from the black diaspora, and victims of police brutality, particularly trans folks of color. In other words, a black, queer, transnational feminism with an emphasis on economic justice is shaping our political moment. The M4BL’s platform reads with great clarity on this matter:

We believe in elevating the experiences and leadership of the most marginalized Black people, including but not limited to those who are women, queer, trans, femmes, gender nonconforming, Muslim, formerly and currently incarcerated, cash poor and working class, disabled, undocumented, and immigrant. We are intentional about amplifying the particular experience of state and gendered violence that Black queer, trans, gender nonconforming, women and intersex people face.

M4BL, then, extends the radical legacy of Dr. King while transcending many of the limitations of the movement’s civil rights forebears, particularly on questions of gender and sexuality.

Does that sound like something 94 percent of Americans can get behind?

The driving force here is “intersectionality,” a social doctrine which assigns highest value to those most “marginalized.” It’s the reason the forthcoming Women’s March on Washington has descended into chaos before it has even begun. As reported by the New York Times, organizers and participants can’t agree on who among them is most oppressed, and therefore most worthy of prominence.

Many thousands of women are expected to converge on the nation’s capital for the Women’s March on Washington the day after Donald J. Trump’s inauguration. Jennifer Willis no longer plans to be one of them.

Ms. Willis, a 50-year-old wedding minister from South Carolina, had looked forward to taking her daughters to the march. Then she read a post on the Facebook page for the march that made her feel unwelcome because she is white.

The post, written by a black activist from Brooklyn who is a march volunteer, advised “white allies” to listen more and talk less. It also chided those who, it said, were only now waking up to racism because of the election.

“You don’t just get to join because now you’re scared, too,” read the post. “I was born scared.”

Stung by the tone, Ms. Willis canceled her trip.

This is exclusion, not inclusion. Contrast that with the conciliatory rhetoric of King in 1963. It’s night and day. King’s dream will never be achieved through the doctrine of intersectionality. It is the polar opposite.

Whatever King’s sincerely held beliefs, however he may have changed over the years, we remember on the third Monday in January that reverend who dreamed of interracial brotherhood. To attain it, we must reject the con put forward by the likes of Black Lives Matter and aspire once more toward a society of true merit.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member