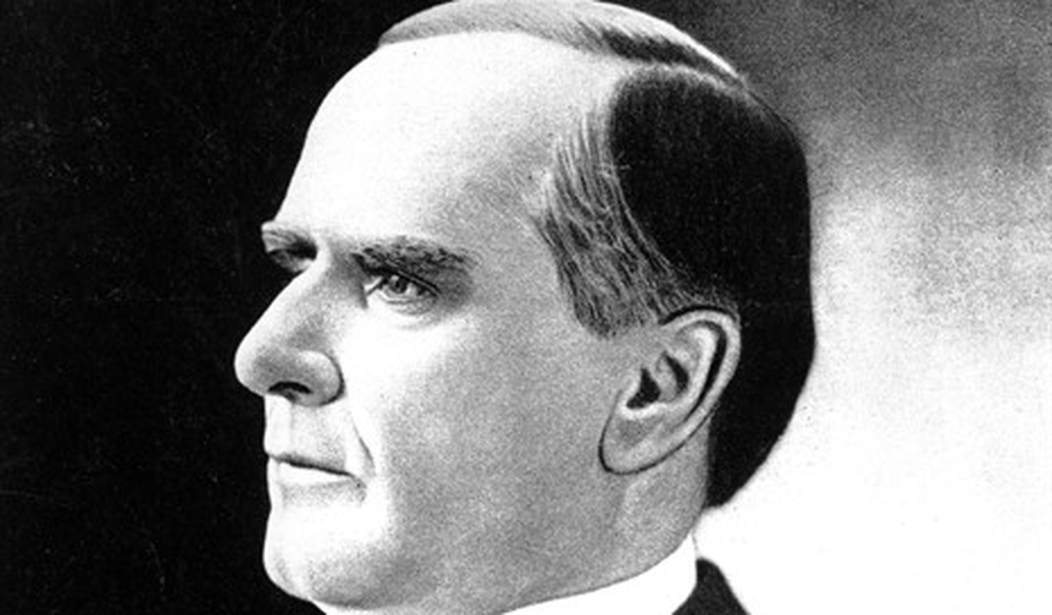

Wednesday, Sept. 6, marked the 122nd anniversary of a day that convulsed the nation and the world at the time but has been nearly forgotten since then: the shooting of President William McKinley, who died eight days later, on Sept. 14, 1901. Although virtually no one remembers McKinley today, he was considered one of the most consequential and important presidents of his time, and the world today is in numerous ways quite a bit like the much more genteel world he lived in. The more things change, as they say, the more they stay the same.

To begin with the end, McKinley’s assassin was a violent leftist. Despite the prosperity that the McKinley administration brought to the country, his age was still one of deep social unrest. McKinley’s murderer, Leon Czolgosz, was an anarchist and associate of the renowned activist Emma Goldman. After hearing Goldman (who openly called for the assassination of rulers she thought unjust) speak about the injustices of American society, Czolgosz determined that “I would have to do something heroic for the cause I loved.” He traveled to Buffalo, N.Y., where McKinley was appearing at the Pan-American Exposition, to kill the president.

The mood in Buffalo was ebullient. On Sept. 5, 1901, the night sky lit up with words spelled out in fireworks: “Welcome President McKinley! Chief of Our Nation and Our Empire!” After Czolgosz shot the president, Goldman charged that McKinley had “betrayed the trust of the people, and became the tool of the moneyed kings.” She claimed that “he and his class had stained the memory of the men who produced the Declaration of Independence, by the blood of the massacred Filipinos.”

Goldman also suggested that the assassination was justified: “Some people have hastily said that Czolgosz’s act was foolish and will check the growth of progress. Those worthy people are wrong in forming hasty conclusions. What results the act of September 6 will have no one can say; one thing, however, is certain: he has wounded government in its most vital spot.” This end-justifies-the-means rhetoric would become a staple of leftist discourse, particularly in the 21st century, when the left in America grew more violent than it ever had before.

In another resonance with the world of today, McKinley had been an America-First president. As a congressman from Ohio, his crowning achievement was the adoption of the McKinley Tariff in 1890, which cemented his reputation as a defender of American industry, the engine of American prosperity. On Oct. 4, 1892, by which time he was governor of Ohio, he explained how the chief beneficiary of protectionism was the American worker:

We used to buy our buttons made in Austria by the prison labor of Austria. We are buying our buttons today made by the free labor of America. We had 11 button factories before 1890; we have 85 now. We employed 500 men before 1890, at from $12 to $15 a week; we employ 8,000 men now, at from $18 to $35 a week. The value of the output before 1890 was less than $500,000; it is $3,500,000 today.

This stance propelled McKinley to the 1896 Republican presidential nomination. The Republican platform committed the party to the gold standard, which prevented the production of so much currency as to lead to inflation. The Democrats nominated a handsome and vigorous 36-year-old congressman from Nebraska named William Jennings Bryan, who had electrified the delegates at the Democratic National Convention with a speech in favor of the free coinage of silver that is one of the most celebrated pieces of oratory in American history.

“You come to us,” Bryan declared, “and tell us that the great cities are in favor of the gold standard; we reply that the great cities rest upon our broad and fertile prairies. Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.”

Bryan sounded notes of class warfare that would become ever more common in American politics: “We do not come as aggressors. Our war is not a war of conquest; we are fighting in the defense of our homes, our families, and posterity. We have petitioned, and our petitions have been scorned; we have entreated, and our entreaties have been disregarded; we have begged, and they have mocked when our calamity came. We beg no longer; we entreat no more; we petition no more. We defy them!” In conclusion, he thundered: “You shall not press down upon the brow of labor this crown of thorns, you shall not crucify mankind upon a cross of gold.”

Related: The Republicans Are Making a Fatal Mistake That They Have Made Before

In a frenzy of enthusiasm over this populist appeal, the Democrats nominated Bryan for president. This marked a sea change for the Democratic Party, as the party that had always favored a limited central government now began to advocate for a massive increase of federal control over the economy, under the cloak of a concern for the common man.

Although Bryan outdid him in passion, rhetorical skill, and the zeal of his following, in the end, McKinley won, quickly leading the country into a period of prosperity due to his America-First principles. That prosperity endured as McKinley began the transformation of the United States into a global power, a change that has been a decidedly mixed blessing at best. In any case, his presidency was so consequential that as late as 1920, presidential contenders were still claiming to be the best exponents of his legacy, the way Republicans did for years with Ronald Reagan.

As the public square becomes more divided and hysterical, McKinley’s most lasting legacy may turn out to be the fact that he was cut down by a leftist, a precursor of the violent and deranged left that is increasingly in evidence in our unhappy land today.