The Foreign Intelligence and Surveillance Act (FISA) was passed in 1978. Since then, more than 35,000 FISA warrants have been issued. Only 12 requests to the Foreign Intelligence and Surveillance Court (FISC) have been denied.

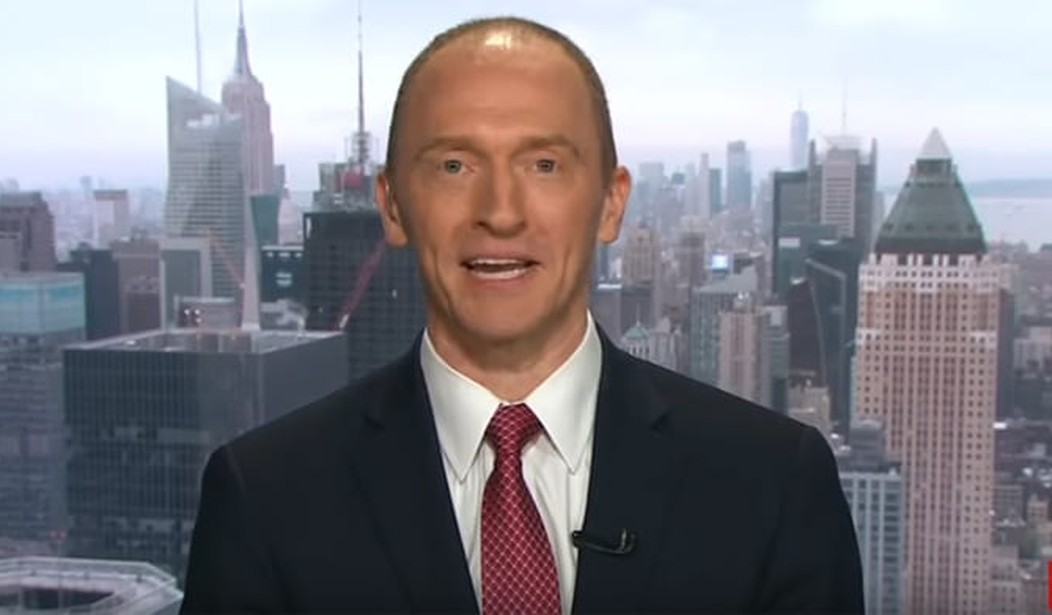

That makes the odds pretty good that a request from the FBI for a FISA warrant to spy on former Trump volunteer Carter Page would have been granted regardless of the anti-Trump bias in the bureau and the questionable provenance of the Steele Dossier.

Indeed, as this Wall Street Journal article points out, the FISA courts are often asked to issue a warrant on tainted or biased information.

Today a number of libertarians and liberals are pointing to a blog post by USC law professor Orin Kerr, who says that failure to disclose the interests of the source is often a non-issue:

Part of the problem is that judges figure that of course informants are often biased. Informants usually have ulterior motives, and judges don’t need to be told that. A helpful case is United States v. Strifler, 851 F.2d 1197, 1201 (9th Cir. 1988), in which the government obtained a warrant to search a house for a meth lab inside. Probable cause was based largely on a confidential informant who told the police that he had not only seen a meth lab in the house but had even helped others to try to manufacture meth there. The magistrate judge issued the warrant based on the informant’s detailed tip. The search was successful and charges followed.

The defendants challenged the warrant on the ground that the affidavit had failed to mention the remarkable ulterior motives of the informant. The affidavit didn’t mention that the “informant” was actually a married couple that had been in a quarrel with the defendants; that the couple was facing criminal charges themselves and had been “guaranteed by the prosecutor that they would not be prosecuted if they provided information”; and that they had been paid by the government for giving the information. The affidavit didn’t mention any of that. A big deal, right?

According to the court, no. “It would have to be a very naive magistrate who would suppose that a confidential informant would drop in off the street with such detailed evidence and not have an ulterior motive,” Judge Noonan wrote. “The magistrate would naturally have assumed that the informant was not a disinterested citizen.” The fact that the magistrate wasn’t told that the “informant” was guaranteed to go free and paid for the information didn’t matter, as “the magistrate was given reason to think the informant knew a good deal about what was going on” inside the house.

If this is accurate, and if it’s also acceptable to include uncorroborated information in warrant applications, this means that the bar for approving government spying against domestic political opponents is significantly lower than most Americans have been led to believe.

Carter Page was not a meth dealer nor was this an ordinary criminal case. This was the FBI requesting permission to spy on the political campaign of a candidate from a political party in opposition to the party of the president sitting in the White House.

It doesn’t get any more consequential than that.

You would think, then, that because the stakes were much higher for the FISA court to issue a warrant, the evidence bar would be set higher as well. Apparently not. The FISA judge appeared inclined to issue a warrant whether the evidence in the Steele Dossier was corroborated or not.

The latest spin is that the FISA judge was told that a “political entity” paid for some of the intelligence, although the FBI is said to have left out the critical information that the “political entity” was the Democratic National Committee and the Hillary Clinton campaign.

Would that have given the FISA judge enough of a reason to deny the warrant request? Again, we’re not talking about a wiretap on some mobster. We’re talking about spying on a presidential campaign. Shouldn’t that information have been given a lot more weight?

The key here is that despite the fact that Page was already the subject of a FISA warrant, issued in 2014 before he volunteered for the Trump campaign, the request to spy on his activities while with the Trump campaign meant that Trump’s aides and staff would also have their conversations recorded. That is an intolerable turn of events unless there’s solid evidence that there were people working for Trump who were traitors to the United States. Only something as serious as evidence of treason would justify this kind of spying on American citizens.

And Mueller, the FBI, and the DoJ have bupkis.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member