Bill Gates is trying to start a whole new industry of new technology sodium reactors that reliably produce electricity while avoiding the use of hydrocarbons. "In Wyoming, Bill Gates moves ahead with nuclear project aimed at revolutionizing power generation," writes the Associated Press.

Gates was in the tiny community of Kemmerer Monday to break ground on the project. The co-founder of Microsoft is chairman of TerraPower. The company applied to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission in March for a construction permit for an advanced nuclear reactor that uses sodium, not water, for cooling. If approved, it would operate as a commercial nuclear power plant.

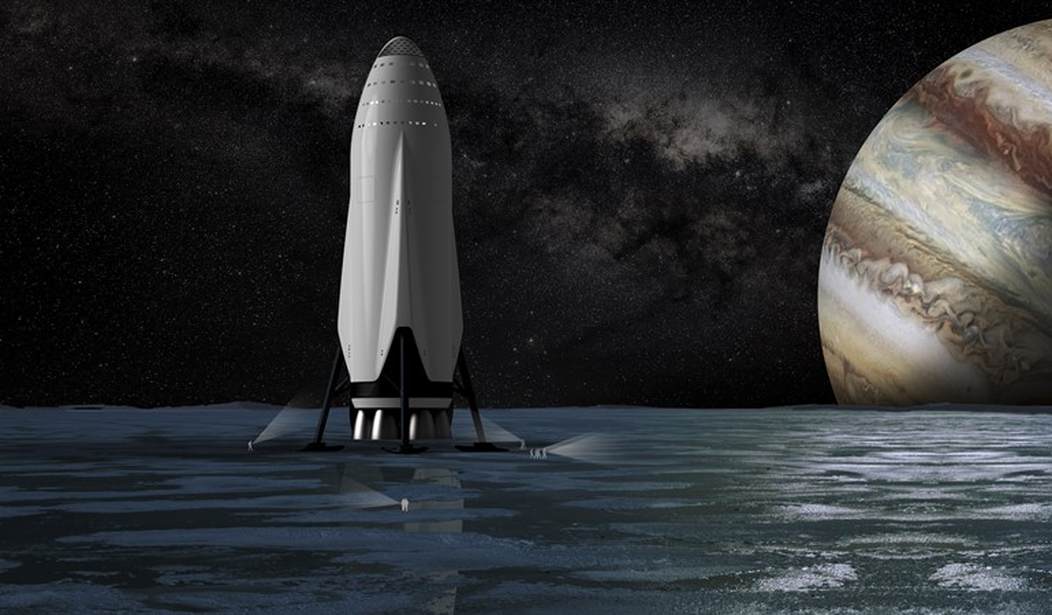

Sounds good, but will it get approval? Should it get approval? One possible hold-up in new technology nuclear plants may be the lack of government inspectors or certifiers qualified in what is terra incognita. Whenever a private firm develops disruptive innovation, as is the case with SpaceX and possibly Gates' Terrapower, a regulatory crisis arises because nobody in the government bureaucracy really understands the new technology and is qualified to judge it. This can lead to delays.

CNN reported that "a top SpaceX executive is accusing government regulators of stifling the company’s progress on its Starship megarocket — potentially opening the door for China to beat U.S. astronauts back to the moon."

There seems no escape from the problem in the case of truly revolutionary industries because by definition nobody, especially the government, knows where the future is heading. Often the brakes or accelerator are applied for no apparent reason. Some readers may recall the recent difficulties with mRNA COVID regulation and the current tussle over controlling the artificial intelligence industry.

Every government faces the same problem. China's response is often to start and stop; initially fund any potentially consequential for reasons of national greatness because it can't miss the boat. But even Beijing is caught on the horns of the regulatory dilemma. After a growth phase, soon things become "unruly," and the Communist Party moves in to reassert control before the whole thing starts again. One China expert reminisced:

The Chinese antitrust authorities should have intervened much earlier to curb the rapid expansion of leading tech firms like Alibaba and Tencent. Instead, they allowed acquisitions by these giants to proceed with little regulatory oversight, let alone constraints, for over a decade. ... Chinese regulation is characterized by repeated cycles of policy easing and tightening. Chinese regulators’ lax approach to AI today could sow the seeds for a regulatory crisis tomorrow.

Unfortunately for the world as a whole, there's no off-ramp in our headlong rush to the future. Declaring a moratorium on research and development doesn't work for the West because if China does not also pause, America won't. If America won't pause developing technology no matter how dangerous, then China won't.

This cycle is how we got into the gain of function trap. Everyone knew from the start that creating mutant pathogens was a dangerous game. But for America, it was impossible to stop because China might continue. For China, it was impossible to stop — for exactly the same reason. Consequently, both countries wound up in Wuhan watching each other but ultimately failing to contain the danger.

There is no such thing as zero risk in conducting experiments. So the question is whether certain gain-of-function research can be performed at an acceptable level of safety and security by utilizing risk-mitigation measures. These strategies for reducing risk include the use of biocontainment facilities, exposure control plans, strict operating procedures and training, incident response planning and much more. These efforts involve dedication and meticulous attention to detail at multiple levels of an institution.

A failure in those institutions may have led to the death of 25 million people in the viral outbreak that followed. Who knows what promise or peril lies in the offing? The problem of regulating new industries involving risks as yet unknown and must involve the application of Bayesian concepts: "Bayesian statistics can be defined as a framework for reasoning about uncertainty. It is based on Bayes’ theorem, which provides a mathematical formula for updating our beliefs in the presence of new evidence. Bayesian statistics allows us to incorporate prior knowledge and update it with data to obtain posterior probabilities."

In simple words, because we cannot know all the dangers in advance that humanity must learn as it goes along. But the capacity to learn is the weakest ability of bureaucracies. Very often bureaucracies only recognize risk (or in the Sputnik case the opportunity cost) after disaster strikes. Government is almost always playing catch up. The pace of risk often depends on political pressure rather than continuously updated knowledge. In COVID's case, one factor distorting risk was Chinese military secrecy.

In the end, American partners very likely knew of only a fraction of the research done in Wuhan. According to U.S. intelligence sources, some of the institute’s virus research was classified or conducted with or on behalf of the Chinese military. In the congressional hearing on Monday, Dr. Fauci repeatedly acknowledged the lack of visibility into experiments conducted at the Wuhan institute, saying, “None of us can know everything that’s going on in China, or in Wuhan, or what have you. And that’s the reason why — I say today, and I’ve said at the T.I.,” referring to his transcribed interview with the subcommittee, “I keep an open mind as to what the origin is.”

When the regulators, like Fauci, don't know what is going on and nobody else does, disaster avoidance is really a matter of luck. If this is how we treated mutant bioweapons, maybe the sodium reactors are as well off regulated as unregulated. It'll be all right on the day.