College students are “routinely accused of crimes they did not commit,” according to a professor of forensic science with more than 20 years of experience investigating violent crime across the United States and Latin America.

Brent E. Turvey, now the director of the Forensic Criminology Institute in Alaska, advanced the claim in his recently published book, False Allegations: Investigative and Forensic Issues in Fraudulent Reports, designed to be a handbook for criminal investigators.

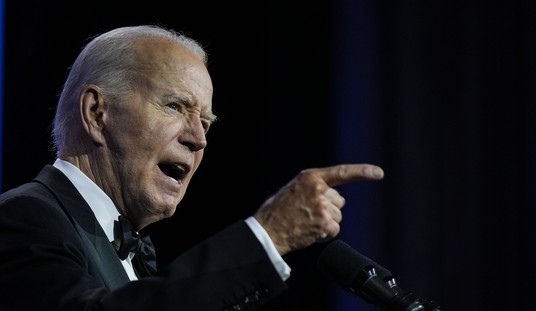

Students are one of a few “vulnerable groups” that routinely either make false reports or are subject to them, Turvey writes, along with people who suffer from addiction, sex workers, public figures, and politicians. Because college students often accuse their peers, false reports are often made by students against other students, Turvey explains.

Investigating claims of sexual assault made by these students is difficult because of their history of making false allegations, Turvey concedes. Because it is impossible to know off-the-bat whether an allegation is true or false, all complaints must be taken seriously, he says.

Thus, investigators must be prudent to investigate all cases “without consideration of personal bias, public pressure, or politics” that could otherwise cloud the investigation.

In an interview with PJ Media, Turvey explained that college students make false allegations of sexual assault to police for a number of reasons. Some students might lie about rape to a close friend or family member, only later to be coerced into telling police. Other students might claim they were raped “as a way to get out of responsibility” or to “explain absence” to a boyfriend or significant other.

Turvey, who is often called in as a third-party investigator to see if evidence can substantiate an allegation, explained that “you have these kinds of cases all the time when the physical evidence tells you that the victim is either lying or having a memory of something that didn’t occur.”

When Turvey is called in to investigate, he often finds that “the physical evidence does not match [the accuser’s] version of events.” This doesn’t exactly mean that the student is lying, though. There are three possibilities: either the evidence supports their claim, there’s not enough evidence to substantiate their claim, or the evidence contradicts their claim.

If there’s not enough evidence to substantiate a claim, that doesn’t mean the rape didn’t occur. (Unfortunately, claims of sexual assault are notoriously difficult to prove, which means many real victims often go without justice.) But sometimes, Turvey said, he finds that the evidence expressedly contradicts a witness’ statement.

Case in point: In one accusation Turvey recently worked on, a young woman claimed that a man sexually assaulted her after breaking through the window to her room. But when Turvey investigated, he found that the window couldn’t be opened from the outside. Further, after reviewing footage from a security camera pointed towards her window, there was no record of a man breaking and entering. That was one such case in which the evidence contradicted a woman’s allegation, he noted.

The psychology behind false reporting is extremely interesting, Turvey said, and his new book dedicates an entire chapter to it. One little known personality trait of false reporters is that they tend to make false allegations multiple times.

“For someone who’s making a false report, they will have usually made one in the past,” Turvey explained. “You’ll have false reporters who will spend their lives making false reports and report on 1-2-3-4 plus people.”

The quest for victimhood often drives these people to make false reports, according to Turvey: “They have no problem doing it, because they want the mantle of victimhood on them.”

They want people to think they’re a victim, and they want all the benefits that come with that — which means different responsibilities, different expectations, financial and emotional benefits and identity. They want the identity of being a victim. There’s perceived social benefits.

Some students, he conceded, simply “need the validation and the attention.”

While allegations made by college students are difficult for police officers to investigate, Turley also said there are similar problems posed by the campus court system. “There are campus court situations in which a victim could be favored, or situations in which an accused student could be favored,” he said.

Just as with law enforcement, “bias, public pressure, and politics” can cloud campus sexual assault allegations, too.

Favoring one side of a complaint over another is a form of bias, he said. Investigators need training to ensure they follow protocols centered around fairness and evidence — and that do not privilege either the victim or the accused student.

“If there’s a claim of sexual assault, I want to know who’s lying. I don’t care who’s lying, I just want to know who’s lying,” Turvey said.

Follow the author of this article on Twitter: @Toni_Airaksinen.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member