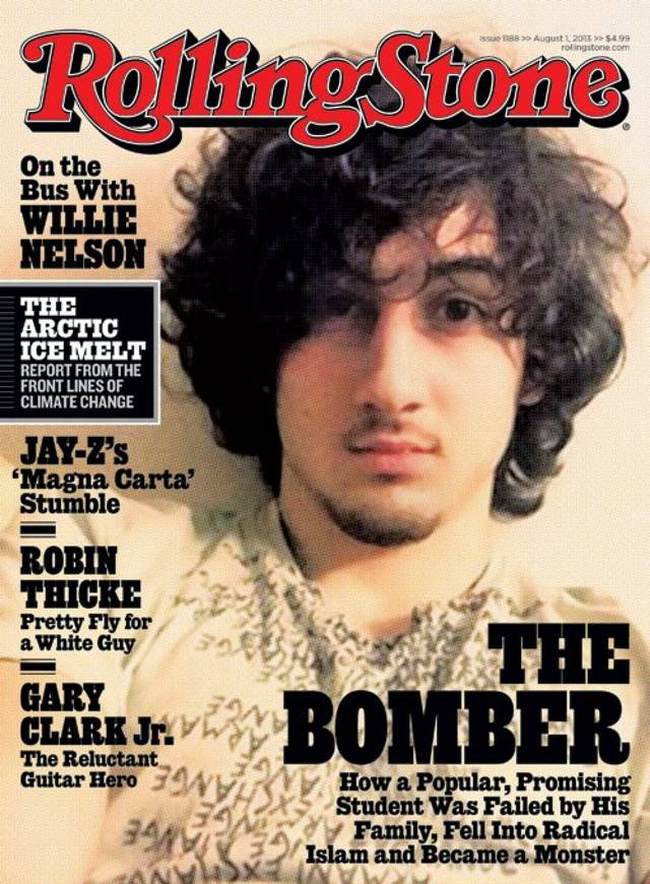

Much of the brouhaha about Rolling Stone’s piece on Dzhokhar Tsarnaev has centered on the rockstar-style photo of the bomber on the cover.

But that’s not the only thing wrong with the article. Take the text, which is an earnest attempt to answer the question: How could a good boy like Dzhokhar go so bad? What secret sorrow, what family troubles or school troubles or other troubles led a young man universally described as unusually charming, magnetic, easygoing, laid-back, cool, and happy-go-lucky to become an Islamic terrorist murderer?

The article fails abysmally to answer the question, although along the way it offers quite a bit of background information about the boy and then the young man it refers to as Jahar, as most of his friends did. But perhaps the author is asking the wrong question. Maybe there’s not that much to explain or understand, if one considers the possibility that the charismatic Dzohkhar may in fact be a psychopath.

How could that be? Despite a common popular misconception that psychopaths are a gloomy sort, not the type of people you’d take to if you were to meet them, that doesn’t really describe the majority of them. The classic text on the subject, The Mask of Sanity, was written in 1941 by psychiatrist Hervey Cleckley. That’s a long time ago, but the work holds up very well today because although we can describe psychopathy, we have learned very little more about its etiology than was known in Cleckley’s time. Here’s his description of the psychopath’s “mask”:

…[T]he [psychopath’s] central personality…[is] covered over by…a perfect mask of genuine sanity, a flawless surface indicative in every respect of robust mental health. .. [T]hose called psychopaths are very sharply characterized by the lack of anxiety (remorse, uneasy anticipation, apprehensive scrupulousness, the sense of being under stress or strain)…

It is my opinion that when the typical psychopath…occasionally commits a major deed of violence, it is usually a casual act done not from tremendous passion or as a result of plans persistently followed with earnest compelling fervor. There is less to indicate excessively violent rage than a relatively weak emotion breaking through even weaker restraints.

Reading Cleckley, and then reading the Rolling Stone piece, one can’t help but be struck by the similarity between his friends’ descriptions of Dzhokhar and Cleckley’s descriptions of psychopaths. Many of Dzhokhar’s friends were deeply puzzled by the cool, chill, laid-back Jahar’s participation in the bombing, and theorized that his more conventionally depressed, angry, and jihadi brother Tamerlan must have “turned” him or controlled or brainwashed him in some way to have accounted for Dzhokhar’s going along with such a violent and cold-blooded act.

Most people would find it hard to believe that Tamerlan, the more ideologically motivated of the pair, could really just say to his brother, “Hey, want to help me bomb people at the marathon?” and that Dzhokhar would say, “Sure, why not?” But if one studies psychopaths, it is much easier to see how that could really be the case. There is no need to postulate some sort of terrible psychological trauma for Dzhokhar, nor any particularly deep influence or mysterious control Tamerlan had over him, if Dzhokhar is a psychopath. It may have just seemed like a good idea to Dzhokhar at the time, and he had no inner core of morality to stop him.

More from Cleckley:

More often than not, the typical psychopath will seem particularly agreeable and make a distinctly positive impression when he is first encountered. Alert and friendly in his attitude, he is easy to talk with and seems to have a good many genuine interests. … More than the average person, he is likely to seem free from social or emotional impediments, from the minor distortions, peculiarities, and awkwardnesses so common even among the successful.

And from the Rolling Stone article:

…[A]fter several months of interviews with friends, teachers and coaches still reeling from the shock, what emerges is a portrait of a boy who glided through life, showing virtually no signs of anger, let alone radical political ideology or any kind of deeply felt religious beliefs.

We don’t know the cause of psychopathy. But whatever it is, it seems present very early in life and is a defect in the moral and empathic senses. The result can be a killer who is able to hide an utter lack of regard for other human beings behind a facade of facile con artist charm, adept at sensing what other people want to hear and delivering it. When such a person meets up and partners with a needier, angrier, more sincerely doctrinaire, and more conventionally motivated sidekick (such as brother Tamerlan), a sinister synergy is born.

Note also the casual, nose-thumbing malevolence of actions of Dzhokhar’s such as these post-attack tweets of his. How could someone be so strangely distant from the dire consequences of his own acts? How to square it with his seeming sweetness and affability? More from Cleckley:

It is not necessary to assume great cruelty or conscious hatred in [the psychopath] commensurate with the degree of suffering he deals out to others. … In [human life] he seems to find nothing deeply meaningful or persistently stimulating, but only some transient and relatively petty pleasant caprices, a terribly repetitious series of minor frustrations, and ennui. …[H]e suggests a man hanging from a ledge who knows if he lets go he will fall…who, furthermore, is not very tired and who knows help will arrive in a few minutes, but who nevertheless, with a charming smile and a wisecrack, releases his hold to light a cigarette, to snatch at a butterfly, or just to thumb his nose at a fellow passing on the street below.

…Having no major goals or incentives, he may be prompted by simple tedium to acts of folly or crime. Such prompting is not opposed by ordinary compunction or concern for consequences.

From Rolling Stone again:

At his arraignment at a federal courthouse in Boston on July 10th, Jahar smiled, yawned, slouched in his chair and generally seemed not to fully grasp the seriousness of the situation, while pleading innocent to all charges. At times he seemed almost to smirk –

There was probably no “almost” about it.

“Listen,” says Payack [the high school wrestling coach], “there are kids we don’t catch who just fall through the cracks, but this guy was seamless, like a billiard ball. No cracks at all….I knew this kid, and he was a good kid,” Payack says, sadly. “And, apparently, he’s also a monster.”

Payack only thinks he knew him, although he can be forgiven for his error. After all, he only knew the mask, as did virtually everyone else Dzhokhar encountered, right up to the moment the bombs went off.

“He was just superchill,” says another friend, Will…

“He was smooth as f—,” says his friend Alyssa, who is a year younger than Jahar…

For all of their city’s collective angst and community processing and resolutions of being “one Cambridge,” the reality is that none of Jahar’s friends had any idea he was unhappy, and they really didn’t know he had any issues in his family other than, perhaps, his parents’ divorce, which was kind of normal.

Maybe they should read The Mask of Sanity. It would teach them a lot more about psychopathy than the Cambridge schools ever did.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member