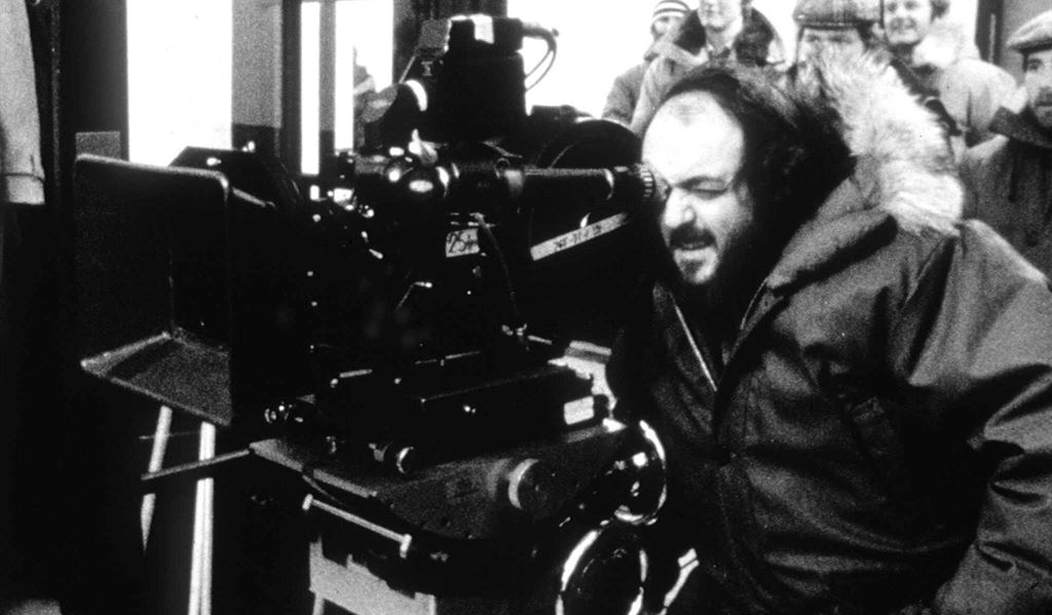

Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket is often remembered as essentially being two movies. Its bravura bootcamp sequence made an unlikely superstar out of the late Lee Ermey and launched Vincent D’Onofrio’s journeyman career. In contrast, most viewers saw the film’s second “half,” (actually the longer of the two parts), as being much more disjointed and difficult to follow. However, I believe Kubrick’s goal in crafting Full Metal Jacket, was to create a “shadow” version of 2001: A Space Odyssey, his epochal 1968 film. All of Kubrick’s post-2001 films make references to 2001 – some obvious, some subtle – and Full Metal Jacket is no exception. Lining up Full Metal Jacket’s structure with 2001 creates some fascinating parallels.

Full Metal Jacket was co-written by Kubrick, Michael Herr, and Gustav Hasford, the author of the novel, The Short-Timers. In his introduction to the illustrated screenplay of Full Metal Jacket, Herr, the author of Dispatches, his acclaimed 1977 “new journalism” look at Vietnam, and the co-screenwriter of Francis Ford Coppola’s epic 1980 Vietnam film Apocalypse Now, wrote that when Kubrick first began his collaboration with Herr in 1980, he asked Herr if he was familiar with Carl Jung’s concept of the “Shadow.” Herr assured Kubrick he was.

At the beginning of the year, Psychology Today described the Jungian Shadow as:

[T]he unknown “dark side” of our personality—dark both because it tends to consist predominantly of the primitive, negative, socially, or religiously depreciated human emotions and impulses, like sexual lust, power strivings, selfishness, greed, envy, anger or rage, and because, due to its unenlightened nature, it is completely obscured from consciousness. Whatever we deem evil, inferior, or unacceptable and deny in ourselves becomes part of the shadow, the counterpoint to what Jung called the persona or conscious ego personality.

* * * * * * * *

Jung differentiated between the personal shadow and the impersonal or archetypal shadow, which acknowledges transpersonal, pure, or radical evil (symbolized by the Devil and demons), as well as collective evil, exemplified by the horror of the Nazis and the Holocaust. Literary and historical figures like Adolf Hitler, Charles Manson, and Darth Vader personify the shadow embodied in its most negative archetypal human form.

For Jung, the theory of the “shadow” was a metaphorical means of conveying the prominent role played by the unconscious in both psychopathology and the perennial problem of evil. In developing his paradoxical conception of the shadow, Jung sought to provide a more highly differentiated, phenomenologically descriptive version of the unconscious and of the id than previously proffered by Freud. The shadow was originally Jung’s poetic term for the totality of the unconscious, a notion he took from philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. But foremost for Jung was the task of further illuminating the shadowy problem of human evil and the prodigious dangers of excessive unconsciousness.

In Full Metal Jacket, this was spelled explicitly in the scene in which a confused Marine colonel asks Joker (Matthew Modine) where he’s wearing a peace symbol on his uniform, but has written “Born to Kill” on his helmet. As Joker replies, “I think I was trying to suggest something about the duality of man…The Jungian thing, sir.”

The Dawn of Marines

The Bootcamp sequence has an obvious similarity to 2001’s “Dawn of Man” introduction. That first “chapter” of 2001 introduces the audience to the alien Monolith, and its ability to somehow impart knowledge to that chapter’s central character, the hominid called Moonwatcher in Arthur C. Clarke’s tie-in novel, and portrayed in the film by actor/mime Dan Richter.

In the “Dawn of Man,” Moonwatcher learns how to use the bone of a tapir as a weapon. Suddenly, after centuries of near starvation, the hominids can kill lesser animals at will when hungry. They also learn how to use the bones to maintain control of their local watering hole against a rival tribe of hominids who attack without knowledge of the benefit of tools. The segment ends with the classic shot of a triumphant Moonwatcher hurling his tapir bone into the air, which is replaced, in one of the 1960s’ most epochal jump cuts, with an orbiting space weapon, circa the year 2001. Four million years’ worth of man’s evolution separated by a single film splice.

In Full Metal Jacket, the new draftees learn about weapons from a rather more prosaic method: their pitiless martinet drill instructor, the ironically named Sgt. Hartman, played by Ermey. Some have argued that the basic training segment of Full Metal Jacket ends with a literal symbolic brainwashing, given that someone will have to clean what’s left of Private Pyle’s skull of the wall of the camp’s latrine after his suicide.

As with 2001, the characters in Full Metal Jacket are cyphers: We know only the most basic of details, once the men are assigned their new names by Sgt. Hartman: Pvt. Joker is the camp funny man and wry satirist. Pvt. Cowboy is from Texas. Pvt. Snowball is black. We only hear the full name of the star of the basic training sequence, Leonard Lawrence, so that Sgt. Hartman can dunk on him: “Lawrence?

Lawrence, what, of Arabia?” Hartman renames Lawrence “Gomer Pyle,” in reference to another bumbling Marine, whom millions of American TV viewers were watching each week on CBS in 1968.

1968: A Tet Odyssey

After Pvt. Pyle’s suicide, the viewers find themselves in Da Nang, Vietnam. Here, “Pvt. Joker,” whom we were introduced to in the boot camp sequence, and his new friend “Rafterman” (Kevyn Major Howard) are flirting with a Vietnamese prostitute when their cameras are stolen by a local thief. After exchanging Bruce Lee-style Kung Fu poses with the Marines, the thief throws the cameras to a friend on a motor scooter zooming through a traffic circle. This move strongly recalls Moonwatcher throwing the bone “into orbit,” as well as bureaucrat Heywood Floyd’s pen floating in zero gravity at the beginning of 2001’s next sequence, and the circular Space Station V, which Floyd was in route to.

Floyd’s trip in 2001 ultimately took him to the moon, where he delivered a speech to his fellow scientists, which set up the discovery of a monolith buried on the moon. In contrast, Full Metal Jacket’s introduction to Vietnam is followed by the Dr. Strangelove-esque speech given by Stars and Stripes editor Lt. Lockhart in a Quonset hut, which sets up the plotting of the rest of the film: the Marines’ efforts in Huế City at pushing back against the NVA’s 1968 Tet Offensive.

In 2001, after Floyd’s speech, the scientists fly out in a moon shuttle to witness the monolith. Similarly, in Full Metal Jacket, Joker and Rafterman fly in a helicopter to Huế, accompanied by a psychotic door gunner, played by actor Tim Colceri, who was Kubrick’s original choice to play the DI, until Lee Ermey talked himself into the part.

Once the helicopter lands, Joker and Rafterman are introduced to “Animal Mother,” portrayed by Adam Baldwin early in his career, a character who is arguably Gomer Pyle’s Shadowy doppelganger:

The Sniper Who Sang “Daisy”

The climactic sniper scenes echo several of Kubrick’s previous movies. In 1964’s Dr. Strangelove, a major plot point is the attempt to rescue the fictitious Burpelson Air Force Base from its lockdown by the insane General Jack D. Ripper, played by Sterling Hayden.

Elements of this scene were reused in 2001, when Keir Dullea’s David Bowman character returns to the Discovery spacecraft to unplug the insane supercomputer, Hal 9000. In Kubrick’s sumptuous 1975 film Barry Lyndon, Lord Bullington, portrayed by future Kubrick behind-the-scenes stalwart Leon Vitali, returns after a self-imposed exile to challenge Barry to a pistol duel, which ultimately transforms the fates of both men. Bullington’s entrance to Barry’s gentlemen’s club is filmed with the same reverse tracking shot that Kubrick used to film Bowman’s return to the Discovery to unplug Hal. A similar shot was used for Dick Hallorann’s (Scatman Crothers) much less successful return to the Overlook Hotel in Kubrick’s 1980 adaptation of The Shining.

In Full Metal Jacket, after a sniper kills several members of the Marines’ “Lusthog Squad,” the Marines’ approach her hiding point in a methodical manner highly reminiscent of the “unplugging” scenes in previous Kubrick films.

Along the way, there are a couple more important “shadow” moments: When Cowboy, played by Arliss Howard is shot by the sniper, he’s quickly dragged by his fellow soldiers around the corner, away from the sniper. Carefully framed behind them is a large burning black monolith. Kubrick told his 1987 Rolling Stone interviewer that this was a mere coincidence, but c’mon. (He also said in the same interview how he admired Fellini’s ability to “makes jokes and says preposterous things that you know he can’t possibly mean.”) As Arthur C. Clarke wrote in the postscript of the 1982 update to his novelization of 2001: A Space Odyssey:

A final comment on both novels as seen from a point now almost exactly midway between the year 2001 and the time when Stanley Kubrick and I started working together. Contrary to popular belief, Science fiction writers very seldom attempt to predict the future; indeed, as Ray Bradbury put it so well, they more often try to prevent it. In 1964, the first heroic period of the Space Age was just opening; the United States had set the Moon as its target, and once that decision had been made, the ultimate conquest of the other planets, appeared inevitable. By 2001, it seemed quite reasonable that there would be giant space-stations in orbit round the Earth and — a little later — manned expeditions to the planets.

In an ideal world, that would have been possible: the Vietnam War would have paid for everything that Stanley Kubrick showed on the Cinerama screen. Now we realize that it will take a little longer.

In light of what happened to the South Vietnamese after the Democrat-majority Congress cut funding for the war in 1974, that’s a remarkably chilly statement from Clarke — weren’t the South Vietnamese entitled to their own “ideal world” as well?

But in any case, whether one agrees with Clarke’s sentiment or not, the burning monolith is but one of many callbacks to 2001 in Full Metal Jacket.

Another shadow moment of a different sort occurs a few minutes later, as the survivors of the Lusthog Squad enter the hellscape the sniper is barricade in, they pass by a wrought iron handrail with a pair of swastikas facing in mirror directions, a reminder of both the original Far East “good luck sign” origins of the symbol, and its hideous 20th century transformation.

2001 ends with David Bowman being transformed by the Monolith into a Nietzschean ubermensch, the next step in man’s evolution, the symbolic star-child looking at planet Earth and wondering what he will do next. In contrast, having made the decision to shoot the female NVA sniper who snuffed out much of his squad, Joker loses his humanity, in voice-over narration, repeats Full Metal Jacket’s strange duality of misogyny and death:

My thoughts drift back to erect nipple wet dreams about Mary Jane Rottencrotch and the great homecoming f**k fantasy. I am so happy that I am alive, in one piece and short. I’m in a world of sh**, yes. But I am alive. And I am not afraid.

And in an echo of Sgt. Hartman asking, “What is this Mickey Mouse sh**,” shortly before Pvt. Pyle murders him and commits suicide, the Lusthog squad marches to base singing the theme song to the Mickey Mouse Show: “Come along and sing this song and join our family. M-i-c-k-e-y-M-o-u-s-e.” The film’s closing credits play, appropriately in a film concerned with the Shadow, the Rolling Stones’ classic 1966 song, “Paint It Black.”

So, am I correct about the Full Metal Jacket-2001 connections? Even when he was alive, Kubrick rarely gave detailed answers about what his films meant. As he wrote to one critic in 1965 who had eventually cottoned on to Dr. Strangelove being both Swiftian satire and an allegory for sex, “I would not think of quarreling with your interpretation nor offering any other, as I have found it always the best policy to allow the film to speak for itself.”

As with all of Kubrick’s mature films, Full Metal Jacket speaks for itself — if you’re prepared to do a fair amount of digging to see what’s lurking in its shadow.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member