Last week we discussed the second season of Star Trek, when show creator and executive producer Gene Roddenberry assembled his best team of producers to rewrite and polish the scripts the show was receiving from freelance writers, but then sacked co-producer (and the show’s best dialogue writer) Gene Coon after too many formula plots. Only a massive letter campaign, which NBC upper management strongly suspected (and correctly so) was orchestrated by Roddenberry saved the show. Which the network punished by burying it for the third season in the graveyard shift — Friday night at 10:00 pm, fatal to a show that relied upon teenage viewers who tend to prioritize their social life around Friday night. To which Paramount responded by cutting the show’s budget (again). The handwriting for the show’s doom was on the wall, and Roddenberry knew it.

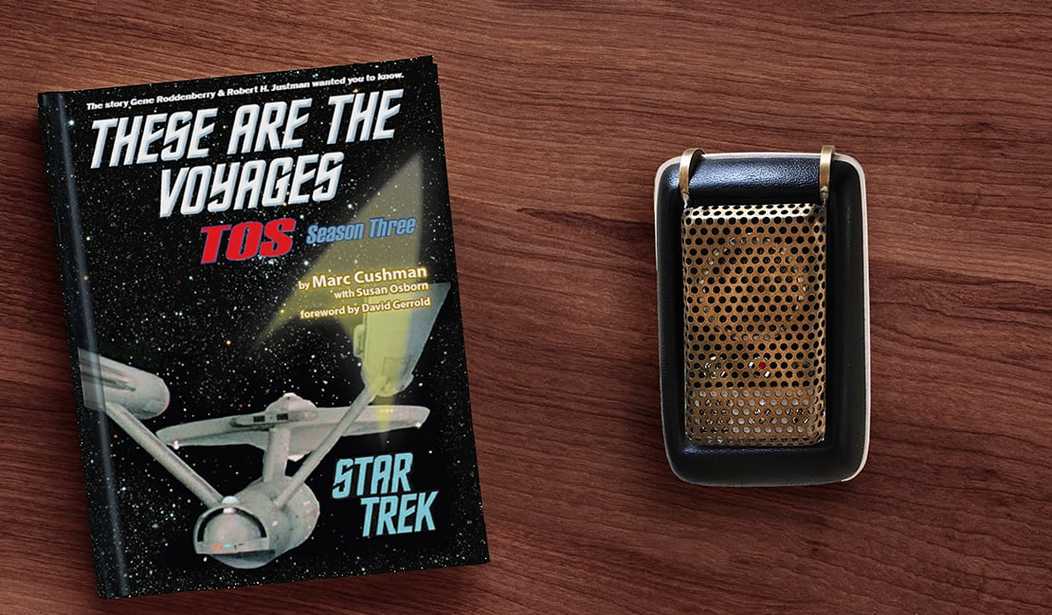

In the introduction to the edition of These Are the Voyages that covered the show’s first season, Cushman says that when he first proposed the books to Roddenberry in the late-1980s, the producer told him that “Of course, it all starts with the script, but writing science fiction for television is just as much about understanding what can and cannot be done in front of the camera and in post-production as it is dreaming up stories. We had no shortage of ideas; the problem was finding affordable ways in which to tell them.”

As Cushman writes in his look back at the show’s beleaguered third season, never was that more true during that production year. Paramount’s budget cuts resulted in only one episode (“The Paradise Syndrome”) being shot on location. Knowing the show was doomed, Roddenberry took Paramount’s paychecks and planned his exit strategy, writing a script for a proposed Tarzan movie. Instead of tasking the loyal and endlessly hard-working Robert Justman to run the show, he brought in Fred Freiberger coming off the hit western/spy spoof The Wild, Wild West, as producer, who in turn brought in his longtime lieutenant, Arthur H. Singer, as his chief story consultant.

However, Roddenberry assigned the first scripts of the show’s third season to his loyal core staffers, now working as freelancers: Dorothy Fontana, John Meredyth Lucas and Gene Coon. The latter man submitted his scripts under the pseudonym Lee Cronin, as he was now employed by Universal to produce the popular Robert Wagner series, It Takes a Thief. That Coon was drastically overstretched showed in the episodes he wrote for the show’s third season, not least of which, its infamous season debut, “Spock’s Brain.” Curiously, the show’s producers, including veterans Roddenberry and Justman, didn’t realize what a stinker Coon had turned in while the episode was being planned and shot. Roddenberry, who feared during the second season that his show was drifting towards the camp of Lost In Space, had, in turn, no idea what was in store for his series during its last year.

Dorothy Fontana submitted the script for “The Enterprise Incident,” a dramatic tale of the Enterprise being captured by the arch-enemy Romulans, a story based on America’s real-life USS Pueblo being captured by the North Koreans in January of 1968. Despite her key role in creating much of Mr. Spock’s backstory, Freiberger did not understand her importance as a member of the writing staff, and curiously, Roddenberry didn’t seem to push his old team on the newcomer to Star Trek, who clearly didn’t understand the formula that was established. As Fontana recounted:

“I was having such a hard time with Freiberger, who didn’t seem to get the show. When you say [concerning ‘Joanna’] things to me like, ‘Well, you can’t do this story about McCoy’s daughter because McCoy is Kirk’s contemporary,’ I realized that, ‘Oh my God, we are in deep trouble.’ And the other one [‘That Which Survives’] just kind of got torpedoed, so I just let them go as stories and I did ‘The Enterprise Incident,’ and got my butt out of there. My agent was a little confused. He said, ‘You know you really like this show.’ And I said, ‘Yes, I do, but it’s not fun anymore. Just get me out of this contract.’ So he did and I went on and did other stuff.”

Freiberger would say to another female Star Trek writer, Margaret Armen, who wrote “The Paradise Syndrome,” one of the third season’s better writers, “Fred came in and, to him, Star Trek was ‘tits in space’ — and that’s a direct quote. I was in the projection room seeing an early episode…. He [Fred] watched the episode with me, smoked a big cigar and said, ‘Oh, I get it. Tits in space.’ That didn’t sit well with me at all….”

In his the third edition of These Are the Voyages, Cushman tries to make the case that the show’s last season wasn’t really as bad as we all remembered it, and this bit of revisionism, at least for me, fails rather badly. Much of Star Trek’s first season and the best of the Gene Coon-produced portion of its second season were among the pinnacle of 1960s American network television. Every aspect of the show — the writing, the acting, the production design, the musical score — during its third season were all far below the bar set by its glory days. Only the special effects in the episode “The Tholian Web,” which Mike Minor, who would go to be production designer on Star Trek’s movies in the 1980, spent months laboring over, lived up to the show’s best days.

But Star Trek as a TV series was never really about special effects — it was a writer’s medium, being led by a producer in its third season who didn’t fully understand how to write the show. It wasn’t entirely Freiberger’s fault, but beginning in the 1970s, when Star Trek began its now endless run in syndication, he took the brunt of the show’s fall. Or as he told an interviewer in 1991, in a quote relayed in Cushman’s book:

Freiberger summed up his agony over Star Trek with a joke, saying, “I thought the worst experience of my life was when I was shot down over Nazi Germany. A Jewish boy from the Bronx parachuted in to the middle of 80 million Nazis. Then I joined Star Trek. I was only in a prison camp for two years, but my travail with Star Trek has lasted 25 years … and still counting.”

One person who’s reputation is somewhat rehabilitated by These Are the Voyages is William Shatner. While Star Trek’s supporting actors have long complained that Shatner monopolized scenes and minimized their characters’ dialogue, Cushman quotes “Tribbles” writer David Gerrold, who says they owed their careers to his endless ability to promote the show during its run:

“Shatner saved their jobs. If it hadn’t been for Shatner, the show would have gone down the tubes…. Here’s a guy who’s the star of the show, who gets more interviews, photo requests, everything requests, more demands on his time, plus he’s in more shots than anybody else, and the rest of the cast is saying, ‘Well, isn’t he being an arrogant prick?’ No, he’s not an arrogant prick, he’s being a workaholic, doing the best to keep that damn show alive. And they can’t see it. And, I feel, instead of writing tell-all books about what a terrible person he was on the set — which I never saw, I only saw a hard working, brilliant, incredibly committed man — they should have all been grateful for the boost to their careers that they got from Star Trek that they couldn’t have gotten any other way, and to be part of something legendary. That’s big.”

Cushman notes that Shatner also worked well with Fred Frieberger in the third season, and he needed all the help he could get with this most difficult show to write and produce.

Another key bit of revisionism is that, in contrast to the conventional wisdom, Star Trek was in its first season, a ratings hit, as Cushman writes at the beginning of his look at Star Trek’s second season:

As the sampling of ratings in the previous volume of These Are the Voyages reveals, Star Trek sporadically placed at No. 1 in its time slot and rarely dropped to No. 3. Most weeks, it drew very respectable numbers, commonly around 30% of the total viewing audience, with a strong 2nd place showing.

In early December 1966, right after A.C. Nielsen declared Star Trek the highest-rated color series from all three networks on Thursday nights, NBC’s Mort Werner told TV Guide he thought “Star Trek could be in for a long run.” A pick-up seemed assured. And why not? NBC, after all, was owned by RCA, the leading maker of color TV sets.

So how did it all go wrong? Well, that’s the subject of much of Cushman’s three books. But suffice to say, NBC’s front office was not enamored of an executive producer who constantly belittled them.

Of course, there’s so much material on Star Trek is available for free on the Internet, and if you’re like me, you’ve absorbed so much information from all of the many earlier “making of” books. Given that a third of each book is spent recapping episode synopses and memorable quotes, the chief reason to read all three editions of These Are the Voyages is the behind the scenes information. And in this area, Cushman’s books on the making of the Star Trek’s three seasons deliver.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member