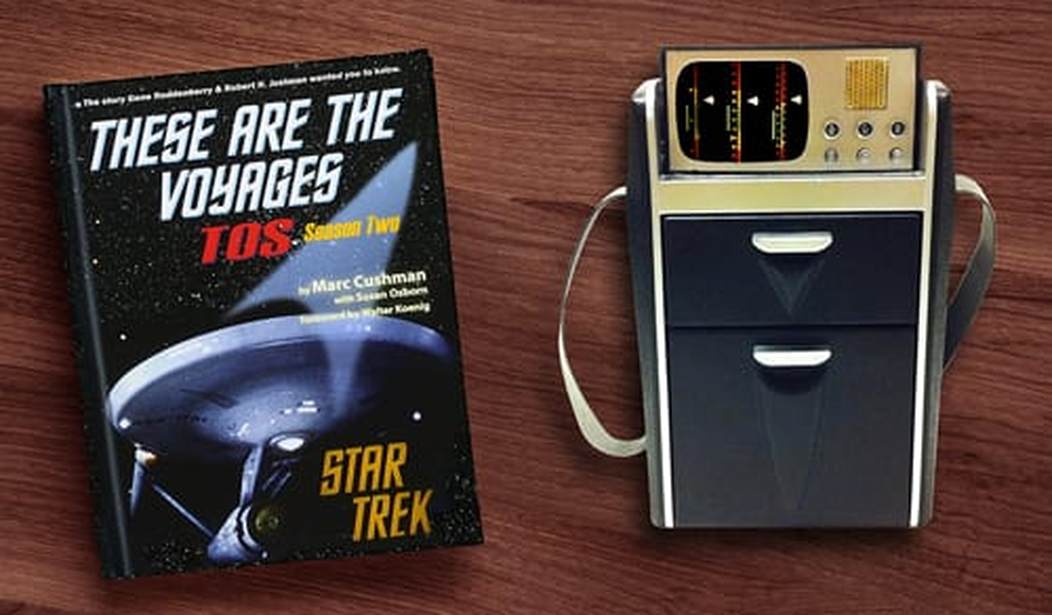

Last week, we explored the first season edition of These are the Voyages, Marc Cushman’s well-researched history of the original version of Star Trek, written with input from many of that show’s behind the scenes team, and authorized by its producers (both sadly deceased), Gene Roddenberry and Robert Justman. This week, we’ll look at its second season, when the original Star Trek reached the peak of its success — then began to fall apart.

One of the most moving sections in Cushman’s books occurs at the beginning of the second season’s edition of These are the Voyages, when he describes the circumstances that caused Nichelle Nichols to reconsider after quitting the show. Nichols had some success as a nightclub singer to fall back on, as she grew bored of being Star Trek’s glorified switchboard operator and having to endlessly repeat the line, “Hailing frequencies open, Captain,” with little else to do as an actress on the show. She had already turned in her resignation to (occasional paramour) Roddenberry when no less than Martin Luther King approached her at an NAACP convention in Beverly Hills and told she should do no such thing:

I said, ‘Thank you so much, Dr. King. I’m really going to miss my co-stars.’ Dr. King looked at me and the smile went off his face and he said, ‘What are you talking about?’ I told him. He said, ‘You cannot,’ and, so help me, this man practically repeated verbatim what Gene said. He said, ‘Don’t you see what this man is doing who has written this? This is the future. He has established us as we should be seen. Three hundred years from now we are here.… When we see you, we see ourselves, and we see ourselves as intelligent and beautiful and proud.’ He goes on and I’m looking at him and my knees are buckling.

* * * * * * * *

That’s all it took. I went back on Monday morning and told Gene [Roddenberry] what had happened. He sat there behind that desk and a tear came down his face, and he looked up at me. I said, ‘Gene, if you want me to stay, I will stay. There’s nothing I can do but stay.’ … He opened his drawer, took out my resignation and handed it to me. He had torn it to pieces. He handed me 100 pieces and said, ‘Welcome back.’”

As Cushman writes, being renewed for a second season brought a whole new set of problems to the series. Leonard Nimoy, who rapidly became the show’s breakout star, wanted a significant raise, in part because he feared (somewhat rightly so, in retrospect) that playing a character with pointed ears and a Moe Howard-esque haircut would result in his being typecast after Star Trek went off the air. Nimoy’s ascent to superstardom angered William Shatner in turn, who believed everyone else in the show’s cast was subservient to him.

Behind the scenes, Roddenberry believed that he had finally assembled a production machine, with himself, Gene L. Coon, Dorothy Fontana, and Robert Justman riding herd over the scripts from outside writers. Justman chose two directors, Joseph Pevney and Marc Daniels, each of whom knew the show’s tone and production techniques and special effects requirements inside and out, to helm the bulk of the second season’s episodes.

However, while Coon wrote dialogue seemingly effortlessly, the crushing deadlines of television led him to create somewhat formulaic episode plots. In the first season, one of his recurring themes was encountering alien species hell-bent on destroying the Enterprise such as the lizard-like Gorn, the swarthy Klingons and the wannabe English nobleman Trelaine, only to have advanced life forms arrive at the end of the episode to either save our heroes’ bacon, or remind them that despite their seemingly mighty starships, they’re looked at as one of the more primitive species in the galaxy, but one with a promising future, or both.

In the second season, Coon’s reliance on formula would become far worse: Star Trek spent numerous episodes visiting what I like to call “the Planet of the Metaphor” – planets that looked suspiciously like the Paramount backlot and ruled by Nazis, a 20th-century Roman Empire, or 1920s gangsters. Any one of those would be a nice change of pace in a season, but this became a recurring formula in the show’s second season. Add to those episodes the Halloween-themed “Catspaw,” set in a castle with black cats and a dungeon in the basement, “Assignment: Earth,” again back to mid-20th-century Earth, and the futuristic Communist Chinese and primitive descendants of American colonials in the Gene Roddenberry-written stinker, “The Omega Glory.” (With its infamous “Ee’d Plebnista!” moment.) By the end of the second season, it must have seemed to the viewer that the USS Enterprise, while allegedly tasked with exploring “Strange New Worlds” in a distant quadrant of our galaxy, sure ran into planets that were knockoffs of our own a lot that season.

In the midst of all that repetition, Coon oversaw one of Star Trek’s most beloved episodes: “The Trouble With Tribbles,” based on a plot submitted by then 22-year-old David Gerrold, fresh out of college, as his first television pitch, but whose dialogue was heavily polished by Coon. Due to the success of “Tribbles,” Coon then oversaw “A Piece of the Action,” set on the aforementioned 1920s gangster-ruled planet that seemed like a spoof of Desilu’s own Untouchables series from the early 1960s. When Coon followed this up with the equally campy “I, Mudd,” Roddenberry became unnerved. With camp the theme of the year at rival CBS sci-fi series Lost in Space, NBC’s Man From Uncle, and ABC’s megahit Batman, Roddenberry did not want to see his science fiction series head in this potentially fatal direction.

As a result, Coon’s role as Star Trek’s best line producer came to an end, Cushman writes:

“Coon and Roddenberry had something of a falling out,” said an anonymous Star Trek insider, as quoted by Edward Gross in Great Birds of the Galaxy. “Nobody’s really talked about it, because the details weren’t very well known, [but] apparently they had a disagreement about the direction of the show or what Coon was doing with the show. I suspect part of it was that Coon was letting the show get too funny. Although the audience responded very well to the humor in Star Trek, Roddenberry had gone off on an extended vacation [sic] and Coon, during that vacation, bought a lot of scripts and pushed a lot of things through production, and the show worked very efficiently without Roddenberry there. Roddenberry came back and found that a lot of changes had been made…. So they had a falling out.”

“I was always determined not to let Star Trek cross over into Lost in Space territory,” Roddenberry said. “I was never opposed to humor in Star Trek, but I did make a conscious effort to draw the line at camp.”

As with Cushman’s previous book, it’s anecdotes such as these that make it a worthwhile read, even if it means passing by overlong story recaps and quotes from episodes that, let’s face it, if you’re in the market for Star Trek “making of” books at this point, you likely already have completely memorized. So be prepared to do a fair amount of fast-forwarding to get to the behind the scenes action.

All the interplay and memo bouncing (decades before email became ubiquitous) in Star Trek’s production office are reminders that while American film critic Andrew Sarris coined the auteur theory in the early 1960s, and film directors such Orson Welles, Stanley Kubrick, Francis Ford Coppola, and Woody Allen wrote and directed some or all of their movies, television has always been a medium of committees and assembly lines.

Once Gene Roddenberry stumbled into the lineup of Coon, Fontana, Justman and himself to oversee Star Trek’s scripts, they created the television show we love to this day. With Roddenberry’s falling out with Coon, it was slowly downhill for the show he created from then on, leading to a decade in the media wilderness, as we’ll explore next week.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member