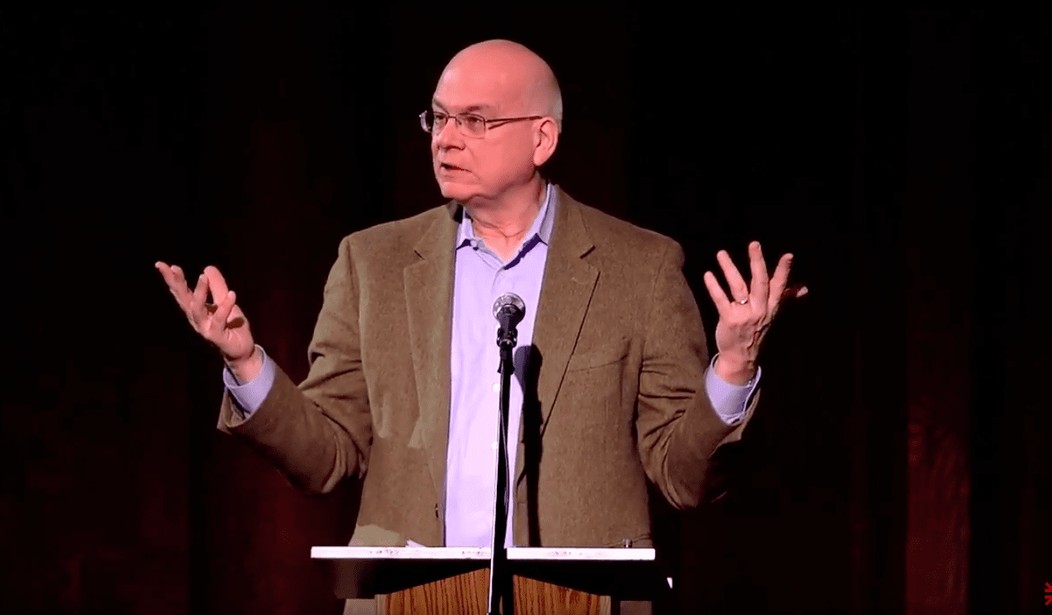

I recently listened to a lecture by a pastor, Tim Keller from New York, who argued that white people need to apologize to blacks for the sin of their fathers’ racism.

He cites two passages from the Old Testament and one general doctrine to support his thesis that we are indeed collectively responsible for the past sins of the group.

The first passage he quotes is Joshua 7, in which Achan takes plunder for himself against God’s directives for the nation of Israel. The entire nation was suffering because of Achan’s individual sin. As punishment, not only was Achan stoned and burned, but his entire family was killed.

Then Joshua, together with all Israel, took Achan son of Zerah, the silver, the robe, the gold bar, his sons and daughters, his cattle, donkeys and sheep, his tent and all that he had, to the Valley of Achor. Joshua said, “Why have you brought this trouble on us? The Lord will bring trouble on you today.” Then all Israel stoned him, and after they had stoned the rest, they burned them.

His conclusion from Joshua 7 is that individuals within a family are responsible for the actions of that family.

His second passage is Daniel 9, in which Daniel confesses and repents for the collective sins of Israel. Keller tries to maintain that Daniel also takes responsibility for the sins of their ancestors when Daniel says, “Our sins and the iniquities of our ancestors have made Jerusalem and your people an object of scorn to all those around us.”

In reference to this passage, Keller says, “I mean I still hear it, though especially years ago when I lived in the South. I heard white people say, ‘Yeah, it’s a shame what slavery did, but I never owned any slaves so why in the world does anybody think that I as a white person now had any responsibility to that community over there at all? I didn’t own slaves.’ But here is Daniel feeling a responsibility for and repenting for things his ancestors did. Why? Because he knows that the culture that he’s part of produced the sins of the past and he’s still part of that culture. He senses the responsibility and the Bible senses the responsibility. He senses the connection.”

From this, Keller concludes that an entire society can be found responsible for and guilty of past sins committed by that culture.

Keller then makes a final case, referring to the sin of Adam, who was the federal representative head of all humanity, chosen by God who had that authority as our Creator. According to the doctrine of original sin, we are all corrupted by and guilty of Adam’s original sin since he represented all of us by God’s decree.

Keller reasons from this specific doctrine that we are collectively guilty for the sins of our ancestors.

Here is why Keller is very wrong in general and in his specific application of this to slavery.

First, regarding his reference to Joshua 7 and the sin of Achan, God made a covenant with the nation of Israel, and they were expected to obey his covenant as a nation. When they violated it, in part or whole, the entire nation was punished because the entire nation, as represented by Abraham, had contracted with God.

This cannot be applied to all peoples in all ages. This is particular to Israel. The United States, for example, has not made a covenant with God to follow particular requirements. George Washington did not enter into a covenant with God like Abraham did as the father of Isaac and Ishmael. God didn’t say to Washington, “As for you, you must keep my covenant, you and your descendants in every generation. This is my covenant that you and your descendants must keep: Circumcise every male” (Genesis 17:9-10).

Second, Keller concludes from the punishment of Achan’s entire family that families are collectively responsible and therefore guilty for the sins of individuals. This also is in error. The punishment here was tied to Israel’s civil law. They had many civil laws, including stoning homosexuals and adulterers. Clearly, this does not apply to all nations in all times. Americans don’t follow the penal codes of Israel that hold families collectively responsible.

As for the citation from Daniel 9, Daniel was a prophet in the royal line of David and represented Israel. Israel was in exile because the nation had rebelled against God — a collective punishment stemming from the nation’s collective covenant with God. Daniel, as their representative, confessed and repented on Israel’s behalf.

As for Israel being held to account for the sins of their ancestors, this too is part of Israel’s covenant, but this passage doesn’t even speak to that exactly. It’s referring more to consequences. Israel had become a scorn to those around them as a result of their disobedience. This can certainly happen when the “sins of the father” are visited on later generations.

We can all admit this certainly does happen. Patterns of behavior and consequences of past mistakes and choices can certainly affect descendents. But this is not the same as saying the descendents are “guilty” of the sins of their fathers.

In each of these examples, Keller is taking a very specific and unique situation in which Israel was treated as an individual entity by God, in which he entered into a covenant with them and holds them collectively responsible.

This does not apply to anyone else except Israel so the argument is moot. Even if you want to say the church has replaced Israel, the civil penal codes and the laws of Judaism do not apply to the church. While Christians are all part of the body of Christ, our covenantal relationship regarding rewards and punishments in Christ — particularly regarding salvation — is individual, not collective.

This is evident from the following verses:

“In those days they will not say again, ‘The fathers have eaten sour grapes, And the children’s teeth are set on edge.’ But everyone will die for his own iniquity; each man who eats the sour grapes, his teeth will be set on edge. “Behold, days are coming,” declares the LORD, “when I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel and with the house of Judah” (Jeremiah 31:29-31).

Fathers shall not be put to death for their sons, nor shall sons be put to death for their fathers; everyone shall be put to death for his own sin (Deuteronomy 24:16).

“The person who sins will die. The son will not bear the punishment for the father’s iniquity, nor will the father bear the punishment for the son’s iniquity; the righteousness of the righteous will be upon himself, and the wickedness of the wicked will be upon himself” (Ezekiel 18:20).

The Gospel is an individual promise with serious collective implications, not the other way around. Collective salvation is a quasi-religious concept reflected in liberation theology, the Social Gospel, and social justice. It’s not Christian theology. We are accountable for our own sins, not the sins of others (2 Cor. 5:10).

Salvation is “collective” only in the sense that Jesus’ atonement is sufficient to cover the sins of every human being. He died “for all.” But every person does not choose to accept his gift of salvation. This decision, which results in salvation, is personal.

If you reason that because we are all collectively condemned by the sin of Adam, we are also collectively redeemed in Christ, you would be forced to embrace universalism — that all men are saved. Otherwise, you would have to reject the efficacy of Christ’s atoning work. If all aren’t saved, it must mean that all don’t personally choose to be saved or that Christ’s work on the cross failed. The latter is simply not true. Hence, we have collective sin (as well as personal sins), but personal redemption.

All humanity is collectively responsible for the original sin of Adam. We have all fallen short of the glory of God. We collectively suffer the consequences of original sin by living in a fallen and turbulent world. We also collectively and individually suffer the guilt and therefore the punishment of that sin — spiritual and physical death.

This doctrine, however, does not extend to any “sin” beyond the original sin of Adam. In other words, we are punished collectively for that one sin, and we suffer because of that one sin. We are collectively condemned because of that one sin, and we are redeemed by Christ because of that one sin. But we are not accountable for the manifold of sins committed by Adam or any other ancestor down through the ages. There are no other “original sins.”

This is why the terminology used by people about America’s “original sin of slavery” is so terribly wrong. If there is an original sin of slavery, who was our representative head? Who chose that person? Who contracted him to represent the collective of all white people in America?

The fact is, there is no “original sin” of slavery in which we are collectively responsible down through the ages. Any individuals, or even any group, who had slaves were guilty of the sin of slavery. They were responsible, not those who came after.

Does all of this mean we don’t need to show compassion for those who have suffered the consequences of sins from the past, sins committed by our ancestors? Of course not. We should take every opportunity to show love and empathy for those who suffer, whether we’re responsible for it or not. We can soothe a troubled soul by showing love instead of ignoring or perpetuating past hurts.

But this does not mean we are responsible for those past hurts, guilty of those transgressions, and therefore worthy of punishment for those sins. Kindness is a virtue because it is shown freely from a heart motivated by love, not compelled by guilt.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member