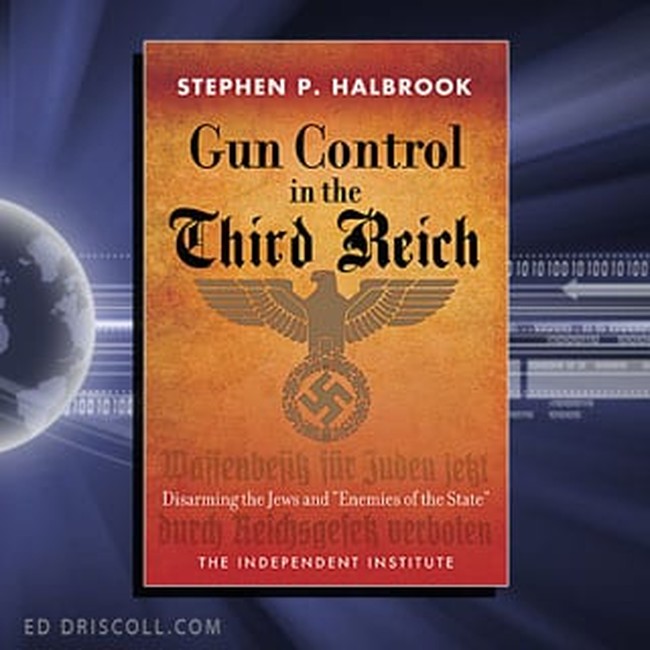

Over the last twenty years, Stephen P. Halbrook’s scholarly work on gun control has become more polished, nuanced, and methodical. His latest book, Gun Control in the Third Reich: Disarming the Jews and “Enemies of the State,” is an astonishing piece of scholarship: complete, careful, and thoughtful.

For a very long time, Americans opposed to gun control have used the example of Nazi Germany’s gun control laws as a warning of what might happen here. Regrettably, not everyone has been careful enough. There is a quote purportedly from Hitler about gun control that starts out “1935 will go down in history” that used to float around the Internet; it does not appear so often anymore because a number of people, including me, demonstrated its falsity.

Part of what allowed bogus quotes like this to survive was that few historians had bothered to research the real history of the Nazis and gun control. Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership did a nice job of obtaining and translating the 1928 and 1931 Weimar Republic gun control laws and the 1938 Nazi gun control law some years ago. But as useful as those translations are, they simply do not compare to what Halbrook has done with his new book.

Halbrook traces the development of German gun control law from the collapse of the Kaiser’s government in 1918 through the post-war chaos, the Weimar Republic’s efforts to prevent the violence of the Nazis and the Communists in the 1920s and early 1930s, and then the ways in which the Nazis used those laws to disarm anyone who they regarded as “enemies of the state” (which of course included all Jews).

In doing so, Halbrook makes use of an astonishing set of sources. His secondary sources are impressive: scholarly histories of the period, such as The Berlin Police Force in the Weimar Republic; specialized works that you might not even expect to exist, such as Der Weg des Sports in die nationalsozialistische Diktatur (The Way of Sport in the National Socialist Dictatorship). Halbrook goes far beyond that, however, with an impressive collection of primary sources, including diaries by people who lived through the time, surviving police records, internal government memos, and court decisions.

Part of what makes a book like this possible is part of what made it so easy to convict Nazis war criminals: the German penchant for documenting everything, and the difficulty in making those documents disappear when it became apparent that the war was lost.

There are many parallels between the laws passed in the Weimar Republic and by the Nazis, and current gun control laws and proposals. For example: the nature and duration of the records that gun manufacturers and dealers were required to keep (p. 135); issuance of gun carry licenses “only to persons considered reliable and only if a need is proven” (p. 107); the use of relatively rare incidents to justify widespread disarmament of “enemies of the state” (p. 155); and the prohibition of firearms with features not generally used “for hunting or sporting purposes” (p. 134).

This is not to say that gun control advocates in America today are planning a police state, concentration camps, and mass extermination. As Halbrook points out, when the Weimar Republic pursued its campaign of strict licensing and registration, they were genuinely trying to deal with a serious violence problem. They picked a solution that did not work, as some police officials of the time pointed out, causing some German states to refuse to go along with the Weimar Republic’s mandatory registration regulations in 1931 (pp. 34-38).

The problem was that, as some pointed out when mandatory registration was under discussion in 1931, “in chaotic times, the lists of firearms owners would fall into the wrong hands, allowing unauthorized persons to seize arms and use them to commit unlawful acts” (p. 29). The lists did fall into the wrong hands — the Nazi government, after the 1933 elections. And they did use them to seize arms, especially from Jews and other “enemies of the state.”

A common argument of gun control advocates against the insurrectionary theory of the Second Amendment is that there was no practical way for opponents of the Nazi government to overturn it. What value could rifles and pistols have in Nazi Germany?

It is indeed possible that an armed German population in 1934 or 1935 would not have made that much of a difference. Hitler was very popular with most Germans, and even German Jews regarded the continual legal disabilities and extralegal injuries imposed on them as insults, best accepted because the alternative was worse. Still, when the time came that German Jews started to be loaded up on railroad cars and shipped to concentration camps, the writing was on the wall, and more than a few knew that they had little chance of getting out of this alive. But by that point, the Nazi government had used the registration lists dating from the Weimar Republic to disarm most German Jews.

Perhaps rifles and pistols in the hands of Germany’s Jews would not have seriously delayed the Holocaust, but the example of the Warsaw Ghetto, where Polish Jews with ten rifles and a few dozen pistols delayed the German Army for six weeks, suggests otherwise.

How could Germany’s Jews being armed for resistance have made anything worse?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member