Samsung got caught faking pictures users took of the moon by using AI to create details that the camera never captured. This raises questions about art, skill, artificial intelligence, and… magic.

The South Korean tech-and-everything-else giant has made great strides in the last three years, using AI to improve low-light and night photography for users of its best-selling line of Galaxy smartphones.

Watch the ad:

As a intermittent photographer, let me tell you: Moon photography isn’t easy, and help is much appreciated. But when does computational photography, as it’s known, cross the line from helping to faking?

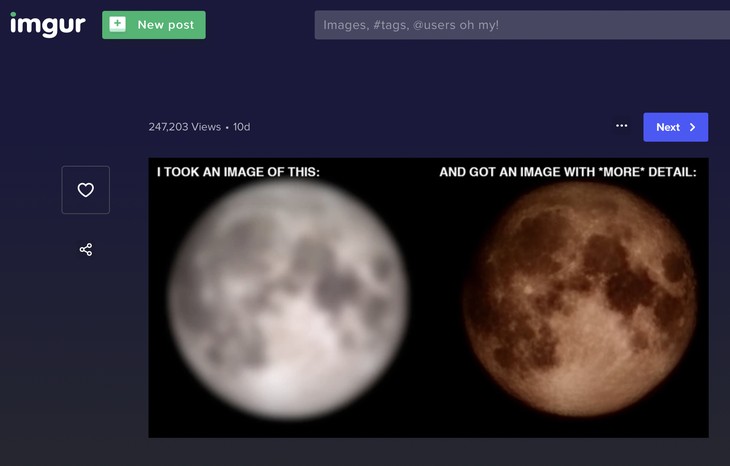

Last week, Reddit user ibreakphotos wanted to put Samsung’s AI to the test to see how much it could improve a photo for “real” and how much was faked. What ibreakphotos did was ingenious, maybe even diabolical. He downloaded a hi-res photo of the moon off the internet, then “downsized it to 170×170 pixels and applied a gaussian blur, so that all the detail is GONE.”

“This means it’s not recoverable” by an AI, he explained, because “the information is just not there.” ibreakphotos then blew up that blurry, postage-stamp-sized reduction to fill his computer screen, dimmed the room, and took a picture of the picture with a Samsung Galaxy.

Here’s the result, side by side with the blurred original, courtesy of Imgur.

Computational photography works behind the scenes to help you take better pictures. It isn’t often appreciated, but your Galaxy or Apple iPhone actually starts taking pictures even before you push the button to take a photo. The camera takes multiple photos every second, intelligently using different exposures and, if there are any problems with focus, lighting, contrast, etc, the computer combines the best parts of each image into one great-looking shot.

But that isn’t what’s going on with these moon photos. The Verge explained that ibreakphoto’s picture of a picture “shows details that [the phone] couldn’t have possibly pulled from the original photo because they were blurred away — rather, Samsung’s processing doing a little more embellishment: adding lines and, in a follow-up test, putting Moon-like texture in areas clipped to white in the original image. It’s not wholesale copy-and-pasting, but it’s not simply enhancing what it sees.”

When you take a great picture of the moon, it feels like you used art and skill to make a little magic happen. When you take a great picture of the moon with your phone, the magic just isn’t there. But does the magic matter when the quality of the two photos is the same?

Maybe it depends on whether you’re the consumer or the creator. If you show me your AI-enhanced photo of the moon, maybe I’ll assume you’re a talented photographer.

Or maybe it doesn’t matter. Maybe the only thing that matters is the magic of human creativity, seen and appreciated by other human beings.

Exclusively for our VIPs: Florida Man Friday: The Naked Visitor From Another Earth

I grew up on the great (and the not-so-great) horror and sci-fi movies of the ’50s through the ’80s. Watching them, I grew obsessed with so many answers to just one question: How did they do that?

Whether it was a massive Star Destroyer flying almost forever over a desert planet while firing “real” looking lasers at its prey, or a slowly melting astronaut finally dissolve into a puddle of his own goo, the special effects guys always blew my mind. How did they do that?

While other kids my age were memorizing the stats of their favorite baseball players, I was reading magazines like Fangoria about special effects greats like Rick Baker, Stan Winston, and Tom Savini.

Practical effects are art — magic, really. If a magician uses clever props and sleight of hand to fool an audience into believing the impossible, a special effects master does the same thing, only in front of a camera.

Digital might look more perfect, but to our lizard brains it seems less real. CGI artists really do create art, and I don’t belittle their work. But the difference between practical and digital is the difference between watching the magician saw a woman in half live on stage, and watching a cartoon of the same trick.

The latter might be beautifully drawn and animated, but the former is magic.

Ironically, CGI was more magical when it was more primitive. The computer-generated water creature in The Abyss shocked and amazed us because we still thought of computer images as blocky things with limited colors. The CGI dinosaurs of the first Jurassic Park impressed us because we had never seen convincing digital creatures before.

But now we know, deep in our lizard brains, that CGI can conjure up anything — even a moon out of a tiny, blurry blob. CGI is a necessary tool in the genre-filmmakers arsenal, but they need to understand its limits. CGI is great for world-building and erasing the wires that make actors appear to fly, but you still need actors working with practical effects created by real-world magicians. Not even the AI enhancements soon coming to every Hollywood CGI department will change that.

If you want a picture of the moon, go take one without an AI-enhanced camera. If it doesn’t turn out, try again and keep trying again until you get it right. When you finally do, you’ll know what you’ve experienced.

With a bit of effort, everybody can make a little magic happen.