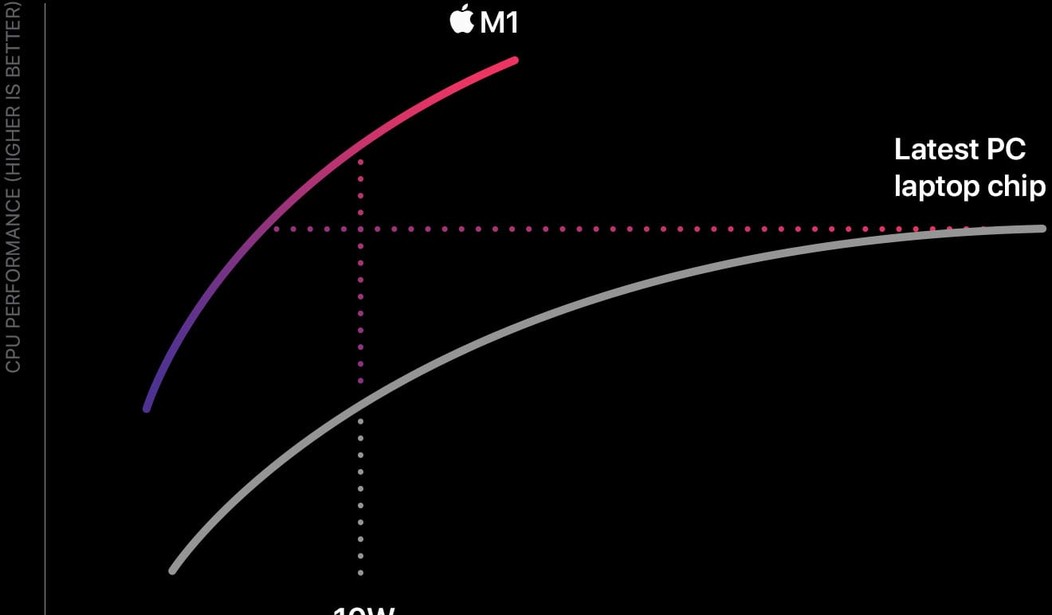

Just released into the wild, the new Apple M1 system-on-a-chip (SOC) already meets or beats some of the fastest processors produced by Intel, and for a lot less money.

In its initial incarnation, the M1 is essentially a laptop-class SOC based on Apple’s successful A-series of ARM SOCs from the iPhone and iPad lineups.

The new M1-powered MacBooks and Mac minis aren’t yet officially in customers’ hands, but a benchmark found late Wednesday on Geekbench shows that Apple’s bottom-of-the-line MacBook Air performs on par with the company’s top-end Intel-powered MacBook Pro.

Before we get to the juicy business angles, let’s do a quick run-through of the numbers.

The Apple M1 MacBook Air model starts at $999, or $899 for students. The 16″ Pro costs a whopping $2,799 without upgrades.

According to Geekbench testing, the M1-based Air smokes the Intel i9-based Pro.

Geekbench scores for 9th-generation Intel i9 laptops like the MacBook Pro are in the 1,000-1,200 range for single-core performance, and 6,400-6,800 for multicore.

While both the M1 and i9 are eight-core chips, the M1 is actually hobbled in a way. Only half of its cores run at full speed and with full capabilities. The other four cores are low-performance varients there to extend battery life when you’re just checking email or web browsing.

In other words, the M1 was fighting with one arm tied behind its back, jumping up and down on one leg, and still won.

It gets better.

Apple is usually pretty conservative about promised battery life, yet claims the MacBook Air will see an unprecedented 15 hours or more in various use cases.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the final, killer detail: The MacBook Air is fanless.

What’s that mean? As I wrote back in August when we saw the first leak from Apple’s Intel-to-M1 development kit:

Think of a CPU or SOC as a car engine. Without proper cooling, an engine has to run very slowly or it’s going to overheat and fry itself. A standard cooling system lets an engine run at its full potential. A beefier cooling system can allow an engine to perform even better than designed.

Like anything else, computer chips generate heat that must be dissipated before it fries itself.

Smartphones and tablets have no fans, and the SOC is packed into a tiny frame that limits how quickly heat can escape. That same SOC, tuned to run comparatively slowly in your smartphone, could be tuned to run much faster in a laptop, and much faster than even that in a roomy desktop enclosure.

The throttled M1 MacBook Air outperforms the fully-cooled Intel-powered MacBook Pro.

When we finally see benchmark scores from unthrottled, fully-cooled M1-powered MacBook Pros and Mac minis, the results ought to be startling to potential buyers, and worrisome to Intel.

Another thing no one elsewhere seems to have mentioned: Apple’s A-series mobiles SOCs have enjoyed single-core speed increases averaging 20%, year over year, since 2013. A single A14 core is about seven times faster than an A7 core from the ancient iPhone 5S.

Intel hasn’t managed those kinds of performance gains in a very long time.

It’s enough to make one wonder what the M2 will do when it debuts, presumably this time next year.

NOTE: Intel does produce a 10th-gen i9 CPU but it’s only slightly faster than the 9th-gen model Apple still uses.

Part of the secret is that ARM’s stripped-down instruction set allows for faster chips that nonetheless only sip at battery power. The other part is that Intel is now two generations behind Taiwan Semiconductor (the company that fabs chips for Apple and Intel rival AMD) in shrinking chips down to the 5nm process. The smaller the process, the faster and more efficient the chips can be.

That’s one reason why Apple’s eight-core M1 is clocked at 3.2ghz while Intel’s i9 is stuck at 2.4.

What does the M1 mean for Intel?

Maybe less than appears at first blush, since Mac sales are dwarfed by their Windows competitors by a nine- or ten-to-one ratio.

In other words, Intel could lose all of its Mac business (which is happening right now) and barely notice.

But by demonstrating what can be done with an ARM-based CPU that runs faster, cooler, and longer than Intel’s x86-based chips — while costing far less! — Apple might have given Microsoft a wake-up call.

Microsoft has made a few halfhearted attempts to get Windows up and running on ARM-based chips but has yet to go all-in.

If Microsoft wants to keep its Surface laptop line competitive, there’s no better time than right now to do something like what Apple has done with the ARM and the M1. Microsoft has long resisted such a move, in no small part because of the rich history of legacy software available to users of the Windows/Intel (Wintel) platform.

Microsoft really only needs three things:

- A suite of ARM-friendly developer tools to boost an ARM-based Windows.

- Something like Apple’s Rosetta 2, that converts legacy Intel apps to ARM code during launch, invisibly and in the background.

- The will to do it.

There are plenty of competitive ARM designs out there (mostly for top-end Android smartphones) that Microsoft could adapt to laptop use, so it isn’t like Redmond would need to start from scratch.

No platform transition is easy, and it’s clear that Microsoft faces one hurdle Apple didn’t: The need to maintain compatibility with jillions of dollars worth of legacy software.

But with the advantages just shown by Apple of ARM vs Intel, virtualization — running a “pretend” Wintel machine via software on an ARM-Windows computer — is more than feasible.

That would still leave Intel with the profitable and fast-growing business of providing super-top-end CPUs for server farms.

But given how much power Google’s and Amazon’s and Microsoft’s server farms draw, is it possible that ARM could be the future there, too?

I got ahead of myself.

I’m an Apple user second and a computer nerd first. I’d love nothing better than to see something like a return to the rapid hardware progress the computer industry enjoyed during the ’90s. Back then, Intel typically needed only about 24 months or so to produce new CPUs that were double or more the speed of the old ones.

I miss that Intel. I miss those days.

(Although I don’t miss spending top dollar every couple of years for Intel’s latest and greatest but I always did it anyway.)

Apple’s M1 line might lead to a return of just those days for Mac and Windows users, alike.

The world of personal computing hasn’t seen competition like this in a long time, and the results will be glorious no matter what operating system you prefer.

But you have to wonder what role, or even how much of a role, once-mighty Intel will play in any of it.