Apple Silicon might just make your next computer much faster — even if you’re a Windows user.

Years in the making, by the end of 2020 Apple will begin moving its entire Macintosh line of personal computers off of Intel CPUs and onto the company’s own chips.

While Mac sales are a tiny fraction of traditional desktop/laptop computer sales, Apple’s decision to go in-house has the potential to shake up the entire industry.

Based on the popular ARM architecture traditionally used in smartphones and tablets, Apple has designed its own “A-series” chips for iPhone and iPad since 2011.

What the company promises to do is adapt the A-series for the even more-demanding world of desktop and laptop performance.

In hindsight, Apple CEO Tim Cook’s Apple Silicon announcement last June probably became all but inevitable as far back as 2013 when Apple revealed the first-ever 64-bit mobile system-on-a-chip (SOC). Labeled the A7 and quickly adapted to the iPhone 5S and the iPad Air and iPad Mini, competitors initially dismissed Apple’s 64-bit effort — about a year before moving to 64-bit SOCs of their own, typically designed and built by mobile ARM-chip giant Qualcomm.

NOTE: A SOC is just a CPU with other chips like graphics and memory all built into a single package.

By moving to a 64-bit design for the A7, Apple wasn’t just giving the iPhone a leg up on the smartphone competition: The Cupertino-based tech giant was likely testing the waters for adapting their A-series chips for the Macintosh.

Apple has done this with the Mac twice before, first moving from Motorola’s 68000 line of CPUs to PowerPC chips, and then from PowerPC to Intel. They’re pretty good at this stuff by now, and the transition to Apple Silicon is expected to go even more smoothly than the transition to Intel did. I was an early adopter of Intel Macs, switching from Windows when the first one debuted. I can tell you from experience that the process was almost seamless.

I also expect Microsoft to get serious about optimizing Windows and Office to ARM-based CPUs, in no small part because of what Apple is about to show the world is possible with ARM.

Apple Silicon is designed by Apple but manufactured by Taiwan Semiconductor.

I mention this because for the first time ever, TSMC is at least a full generation ahead of Intel on producing the smallest, fastest chips at scale, and is on track to beat Intel by two generations later this year.

Needless to say, Intel has stumbled in recent years, failing to live up to promises to reduce the size of their x86-based silicon transistors and thus failing to make their Core and Xeon CPUs faster and more energy-efficient.

Nevertheless, Apple was almost certainly planning to abandon Intel even if Intel had lived up to its promises.

Cook said in 2011 that the company needs “to own and control the primary technologies behind the products we make.” Nothing is more central to a computer than the central processing unit that acts as the “brain” inside every smartphone, tablet, and personal computer.

Early word is that Apple Silicon-fueled Macs will smoke what Intel has to offer for competing Windows computers.

This summer, Apple released its Developer Transition Kit (DTK) to help developers make the move from writing code for its Intel-based Macs to ARM. Essentially a two-year-old A12 SOC inside a Mac Mini case, DTK benchmarks somehow (cough, cough) leaked to the press despite Cupertino forbidding any such thing.

The numbers were impressive:

As for the results, the Apple silicon-equipped developer kits average 811 for single-threaded Geekbench and 2781 for multi-threaded. That’s about 20 percent slower than the entry-level i3-1000ng4 powered Macbook Air’s single-core results and 38 percent faster than its multi-threaded results. Higher-end Macs produce much higher numbers, though.

What’s impressive about these leaked numbers is that they’re not for Geekbench running natively in ARM mode.

In other words, an underclocked, two-year-old Apple Silicon SOC — designed for a tablet — already performs on par with a similar Intel CPU from this year running at a higher clock speed.

But as one Ars Technica commenter noted, Apple Silicon’s performance has implications far outside the comparatively tiny world of Mac buyers:

These numbers are from running in x86 emulation, and they are better than the [Microsoft-made] Surface Pro X running in native ARM64. That is pretty impressive, even before you consider that the SOC is older and clocked-down.

From my experience with porting apps to Windows On ARM, native ARM64 is 2 to 4 times faster than emulated x86. I have a very strong feeling that the ARM Macs are going to be really, really good.

Running translated code is always slower than running native code, but Apple Silicon still performed ably.

What’s really interesting however is the performance we haven’t yet seen an A-series SOC do — but that we’re about to see.

Because so far, no A-series chip has been allowed to perform to its full potential.

Think of a CPU or SOC as a car engine. Without proper cooling, an engine has to run very slowly or it’s going to overheat and fry itself. A standard cooling system lets an engine run at its full potential. A beefier cooling system can allow an engine to perform even better than designed.

Like anything else, computer chips generate heat that must be dissipated before it fries itself.

Smartphones and tablets have no fans, and the SOC is packed into a tiny frame that limits how quickly heat can escape. That same SOC, tuned to run comparatively slowly in your smartphone, could be tuned to run much faster in a laptop, and much faster than even that in a roomy desktop enclosure.

If a two-year-old Apple Silicon mobile SOC like the A12 (with four cores) can keep pace with a current four-core Intel desktop CPU, then imagine what this year’s A14, clocked up to desktop speed, will do.

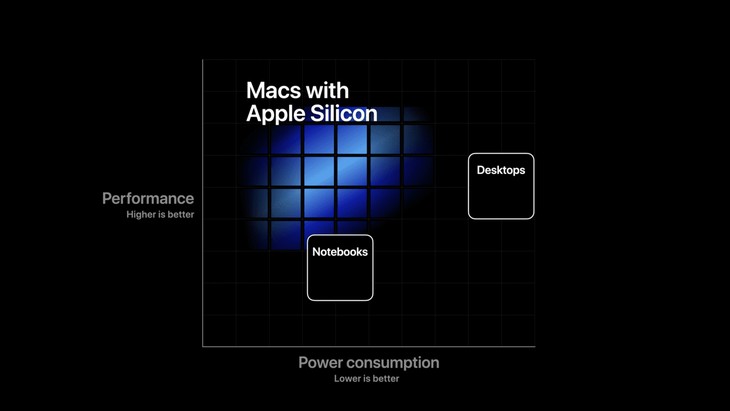

Tuning a chip can mean more than just cranking it up to 11. Tune it only a bit faster, and you can get more battery life instead of more performance.

So Apple could decide to strike a balance between performance and battery life. The first Apple Silicon-based MacBook might be every bit as fast as an equivalent Windows computer, but get hours more battery time between charges.

Apple might entice some Windows users over to Mac with such a computer.

Maybe.

ASIDE: My gut says that Apple practically ignored the professional community for too long, and that most remaining Windows users are too price-conscious for Apple to find many more switchers. They don’t even make “switchers” ads anymore.

What Apple might do, however, is force Microsoft to get serious about porting Windows and Office fully to ARM. Microsoft has made some moves towards ARM computing but has yet to commit to fully ARM-compliant code. Apple Silicon’s potential competitive advantage in performance and/or battery life might finally force Redmond’s hand.

Where would that leave Intel in the desktop space? Intel rival chipmaker AMD isn’t wedded to the x86 architecture the way Intel is, and might easily shift in the ARM-based winds. Intel could lose a big chunk of its high-margin x86 business to the cutthroat, low-margin world of ARM.

Intel’s co-founder, the late, great Andy Grove, was fond of saying, “Only the paranoid survive.”

It’s long past time for Intel — one of the great American tech pioneers — to get paranoid again if the company is going to survive as we know it.

UPDATE: The first ARM-based Mac might be a resurrected superlightweight 12″ MacBook with a radical 15-20 hour battery life and weighing less than 2.2 pounds.

While the tiniest MacBook has a limited market, that reputed battery life (up from 9-10 hours) gives you some idea of what Apple Silicon will be capable of.