In the darkest hours of August 6, 1945, Colonel Paul W. Tibbets and his crew aboard the modified B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay took off from North Field on Tinian in the Central Pacific Ocean to carry out the innocuously named Special Mission 13.

Enola Gay was part of a strike group including no fewer than three weather reconnaissance variants of the B-29, and another specialized Superfortress named Top Secret whose only job was to measure the blast created by the only bomb carried aboard Tibbets’ plane.

Major Claude R. Eatherly’s Straight Flush was the B-29 tasked with reporting weather conditions over Hiroshima, the primary target of Special Mission 13. If weather conditions were less than ideal, then Kokura and Nagasaki were next in line for the “Little Boy” atomic bomb cradled in the belly of Enola Gay. With Tibbets still an hour out, Eatherly radioed ahead, “Cloud cover less than 3/10th at all altitudes. Advice: bomb primary.”

“Primary,” needless to say, got bombed.

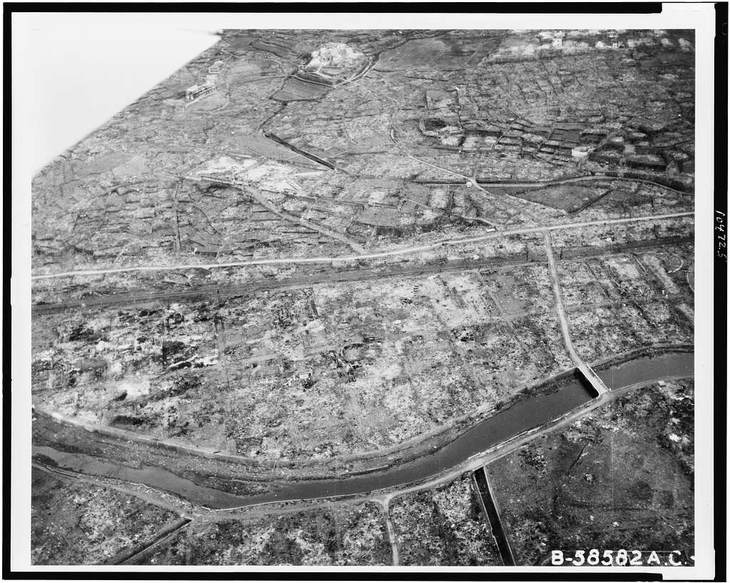

Tibbets began his bomb run — a specialty maneuver Tibbets designed himself, specifically for dropping atomic bombs while getting the bomber and crew safely away — at 8:09 a.m. “Little Boy” was released six minutes later, and its fall retarded by a parachute, detonated 44.4 seconds later at an altitude of 1,900 feet — and only 800 feet from off the aim point.

In a flash and a firestorm, somewhere between 90,000 and 146,000 of Emperor Hirohito’s soldiers and subjects were dead.

Three days later, Special Mission 16 took to the skies under the command of Major Charles W. Sweeney and his modified Superfortress, Bockscar. Although Bockscar carried a more powerful bomb — “Fat Man” — local conditions nevertheless meant fewer dead on the ground, with about 22,000 to 75,000 killed by immediate effects.

And countless lives were saved… on both sides.

These twin bombings, some say, were calculated acts of murderous racism.

With the 75th anniversaries of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings this week, the Progressive 2020 Hindsight Crowd is out in force, questioning or even condemning President Harry Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb.

Segregation in our WWII military remains a stain on our national honor. In practical terms, it was also a detriment to our warfighting capability in a total war requiring full national effort.

But it was Truman who would soon desegregate the military. It was also Truman who spared countless white, yellow, brown, and black lives in August of 1945.

Let me show you how Truman’s decision to tear the heart out of two Japanese cities was a profoundly necessary and moral decision.

We’ll start with a look at the challenges of winning the war on acceptable terms, as they appeared to our war leaders and planners in 1945.

If you want to gain a deep and detailed appreciation for the situation in the summer of ’44, I highly recommend Norman Polmar and Thomas B. Allen’s excellent Code-Name Downfall: The Secret Plan to Invade Japan-And Why Truman Dropped the Bomb.

For now, though, the short version will have to do.

Broadly speaking, Navy leadership believed that Japan could be starved into submission via naval blockade and ariel attacks on the country’s rice paddies. The process might have taken two years or longer and involved as many as 10 million deaths and unimaginable agony — all the horrors of the Seige of Leningrad on a national scale.

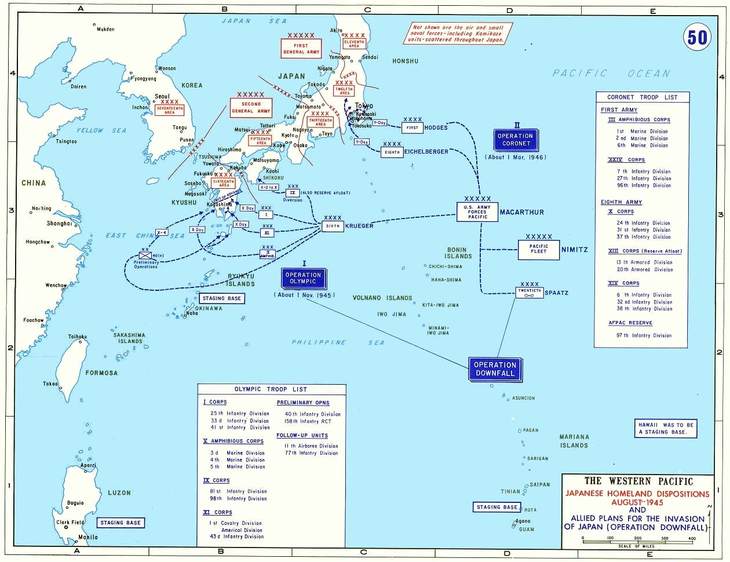

Also speaking broadly, Army leadership was pushing forward with Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s Operation Downfall, a two-stage invasion of the Japenese home islands that would have made D-Day look like two little kids playing cops and robbers in the back yard.

Scheduled for November 1, the first stage of Downfall was Operation Olympic to seize the southern third of Kyūshū, the southernmost of Japan’s home islands.

There, airbases and ports would be developed to support Operation Coronet, the invasion of Honshu that would culminate in the taking of Tokyo. Fifty-four divisions were to take part, compared to just ten required to take Normandy from the Germans on D-Day.

D-Day By the Numbers, By the Men

More than 6,000,000 American and British Commonwealth soldiers, sailors, marines, and airmen would be required for the effort. How many of them would have to die was a subject of much debate. MacArthur’s people low-balled the casualty estimates, greatly under-estimating Imperial Japan’s remaining strength.

National Interest reports:

Operation Downfall would have made Okinawa look like a picnic. “The often-repeated common wisdom holds that there were only 5,500, or at most 7,000, aircraft available and that all of Japan’s best pilots had been killed in earlier battles, writes historian D.M Giangreco “Hell to Pay: Operation Downfall and the Invasion of Japan 1945-47.

“What the U.S. occupation forces found after the war, however, was that the number of aircraft exceeded 12,700, and thanks to the wholesale conversion of training units into kamikaze formations, there were some 18,600 pilots available. Most were admittedly poor flyers, but due to the massive influx of instructors into combat units, more than 4,200 were rated high enough for either twilight or night missions.”

At Okinawa, this piece reminds us, we suffered “more than 50,000 U.S. casualties, a quarter-million Japanese military and civilian dead, and more than 400 Allied ships sunk or damaged.”

Some picnic.

The Joint War Plans Committee (JWPC) believed Olympic would cause between 130,000 and 220,000 U.S. casualties, and that the number of U.S. dead would be between 25,000 to 46,000.

The real situation was probably far worse than the assumptions underlying the JWPC’s estimates.

Also for our VIPs: Thoughts on July’s Record Gun-Buying Spree

Japan’s war planners didn’t have any secret decoder ring alerting them to Operation Downfall, but they could read a map just as well as MacArthur could. They correctly predicted that MacArthur would come for them first in southern Kyūshū, and had reinforced the island’s defenses with everything from crack soldiers to teenage girls armed with bamboo spears. The kamikaze effort, as noted above, was going to be worse than anything we’d yet seen.

The Japanese Army had even correctly estimated which beaches would be used for the initial landings, and which routes inland — there are few on rocky Kyūshū — the Allies would use. The entire southern half of the island had been set up as a kill zone for Allied troops, guarded by soldiers and subjects alike.

Telegraph reports:

The fanatical war minister, General Anami, insisted that Japan should fight to the bitter end with the same techniques and tenacity employed at Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

All women and children, spurred by the pre-invasion song “One Hundred Million Souls for the Emperor,” had been equipped with a sharpened bamboo spear in preparation for a fanatical defence.

The Imperial Government had mobilized “100 million souls for the Emperor.” What that meant was, every Japanese subject was a solider, duty-bound to kill an American or Commonwealth soldier before dying themselves.

And the Japanese people, after centuries of emperor-worship, were largely eager to do just that.

Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson didn’t buy the JWPC’s numbers and commissioned his own report. Stimson’s people counted on between 1.7 and 4 million Allied casualties with 400,000 and 800,000 dead.

In other words, a “successful” invasion of the Japanese Home Islands likely would have increased America’s war dead by anywhere from about 50% to 100%. That’s hundreds of thousands of additional “regret to inform you…” telegrams sent to grieving war widows, mothers, and fathers.

Stimson’s study also estimated that between five and ten million Japanese would die, either from direct fighting, bombing, starvation, or exposure.

That’s not quite “100 million souls for the Emperor,” but given Japan’s wartime population of 71 million, it would have been shockingly close.

Also for our VIPs: Joe Biden’s Veep Delay Underscores a Campaign and a Candidate in Chaos

After three-and-a-half years of fighting and more than 600,000 Americans killed in action, Truman owed it to the American people to bring about Japan’s unconditional surrender with as little bloodshed as possible.

My studies of the Pacific Campaign have convinced me that Operation Downfall would not have led to the downfall of Imperial Japan’s militaristic governing clique.

The bloodbath on Kyūshū might have been so bad that President Harry Truman might have settled for a negotiated peace leaving Imperial Japan’s ruling war clique largely in place. After the horrors of the Central Pacific campaign — exquisitely detailed in James Hornfischer’s The Fleet at Flood Tide: America at Total War in the Pacific — the razing of Manilla, the Bataan Death March, the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor, the Rape of Nanking, and all the rest…

…well, Japan’s conditional surrender was not an option Truman could entertain.

And yet, the sheer number of death notices from the Kyūshū invasion could very well have turned the American people against prosecuting the war to its necessary end.

Therefore, victory in the Pacific with minimal bloodshed required an act of violence so shocking that it would force Hirohito to reverse course and order his people not to fight.

Otherwise, “100 million souls for the Emperor” was on, and the unconditional surrender required for world peace was probably off.

Truman did the right thing. The necessary thing. The moral thing.

He unleashed the atom bomb and brought decades of Imperial Japanese conquest and atrocities to an end, without suffering even one more American combat fatality.

Truman’s decision saved millions of Japanese lives, too.

Some systemic racism, eh?

There had been much discussion at the highest levels of the Truman White House and within the military over the best way to deploy Fat Man and Little Boy — if at all.

Army Chief of Staff George Marshall felt the U.S. would be “in a stronger position in any postwar environment” if we didn’t go nuclear against Japan. Admiral William Leahy was eager to use almost any means to cause the greatest destruction to Japan, and yet felt that using an atomic bomb against a city would be “barbaric.” The Army Air Force’s thinking, best represented by 8th Air Force Commander Lieutenant General Ira C. Eaker and Air Force Chief of Staff General Henry Harley “Hap” Arnold were both eager proponents of victory through strategic bombardment. If that included nukes — a political, not military decision — they were fine with it.

Also discussed was the option of demonstrating the atomic bomb’s destructive power to Imperial Japan’s ruling military clique.

The Franck Report, signed by several prominent nuclear physicists, urged:

A demonstration of the new weapon may best be made before the eyes of representatives of all the United Nations, on the desert or a barren island. The best possible atmosphere for the achievement of an international agreement could be achieved if America would be able to say to the world, “You see what [a] weapon we had but did not use. We are ready to renounce its use in the future and to join other nations in working out adequate supervision of the use of this nuclear weapon”

However, a demonstration was deemed to likely be ineffective.

In the end, Truman looked at the various scenarios for ending the war, America’s growing war fatigue, various casualty projections, and authorized the use of atomic weapons. The targets chosen were both of military significance to continued Japanese war-making.

If anyone of any importance was advocating “Let’s kill all the filthy Japs with all the atomic bombs,” there’s no historical record of it.

When Imperial Japan abruptly surrendered following the Nagasaki bomb and the unstoppable Soviet push into Japanese-held Manchuria, our troops went overnight from trying to kill every Japanese soldier they could, to sharing their rations with the defeated enemy.

President Franklin Roosevelt’s decision to intern Japanese-Americans based solely on their race will always remain a stain on his otherwise impressive record as a war leader. Temporary internment due to security concerns during wartime is hardly evidence of systemic racism, however.

Then there’s the elephant in the room that the “America is racist!” crowd does its best to ignore: we developed the atom bomb to counter Germany, not Japan.

Had the war in Europe dragged on, as some had feared, into 1946, then the first bomb(s) would have been dropped on German cities. If the bomb had been ready to go in 1944, as some had hoped, it would certainly have been used against Germany.

That’s right: the U.S. Army’s U.K.-based Eighth Air Force would have nuked the hell out of history’s most virulent white supremacists.

So while it’s unfortunately true that there were racists within the U.S. government and military, if the U.S. were systemically racist as its wokest critics claim, in WWII we would have taken the side of Germany and Japan, two countries ruled by cliques with delusions of racial superiority.

I’ll leave you with one final thought, a question that nags me on occasion.

What motive ought we ascribe to people who try to paint the great liberators of World War II as the bad guys?