Iran’s mullahs’ regime is feeling frisky again, attacking oil tankers in the Persian Gulf, shooting down an American drone, and of course there’s always its ongoing support for terrorists and rebels throughout the Arab Middle East and Israel, too. Does this mean war?

On Friday, President Trump briefly authorized a retaliatory strike against the regime, before reconsidering and calling it off. Trump concluded that he is “in no hurry” to confront Iran, and that a strike wouldn’t have been “proportionate to shooting down an unmanned drone.” My own thought is that the president should have kept that last thought to himself, but I find no fault with his assessment. It may well be that Trump was never serious about launching an attack this time, but allowed the target list to leak on purpose, as if to say, “Do not tempt me a second time.”

But the fact of the matter is that there are “no great options” for dealing with Iran, as Gray Connolly tweeted in May. It’s a must-read thread, but let me give you a few highlights.

Connolly first notes Iran’s strategic advantages:

• it has circa 80 million people

• it has an enormous military infrastructure

• it has strategic depth of Greater Khorasan

• it is too large to either invade or wisely ignore

He goes on to argue that “Iran is the ancient hegemon, an unavoidable crossroads, a bullying power and an enabler of terrorists, proxies & insurgents that are useful to Tehran.” That doesn’t mean we need to just give in to Iran’s imperial ambitions, because “anyone pretending you simply do nothing or fight a war is not being realistic.”

So we need something in between. Something like the course President Trump has pursued even before exiting the awful nuclear deal last year: Hurt them financially with sanctions, while allowing America’s oil boom to continue unabated, thus putting severe restrictions on Tehran’s room for maneuver. As Richard Fernandez noted on Friday:

Iran only gains by raising tensions in the Strait, upping the price of oil. But actually closing the Strait would be political, if not national suicide. Most of the oil passing through Hormuz (about 11/17ths) is bound for the Straits of Malacca en route to China, Japan and Korea. If Tehran actually closed the Straits, by mining it for example, they would essentially be blockading China.

There’s still a mighty temptation — I know, because I share it sometimes — to use air power to topple the theocrats who have cruelly ruled Iran, and waged war on America and our friends, for 40 years. And perhaps things will deteriorate to the point where such action becomes necessary, although I would certainly hope not. “All we are saying/is give sanctions a chance,” as John Lennon should have sung, “And failing that/maybe we’ll bomb you back to the Stone Age.”

But even if the mullahs were to miraculously enter self-imposed exile tomorrow, taking their entire rotten regime with them, we might not find that to be the panacea we’d hope it would be. Before we get to that, though, let me backtrack a bit.

I’ve been playing strategy games for about ever, and among my Top Five is Paradox’s long-running series, “Europa Universalis.” The game allows you, with a vertigo-including level of detail, to play as any country in the world, on a timespan running from the mid 15th century up through the end of the Napoleonic Wars. One of the game’s key mechanics is core territories, and even though “EU” is just a game, cores are a vital concept when looking at the real world, too.

Cores are those territories that nearly everyone agrees belong to a certain country. If you hold one of your neighbor’s core territories — which will be prone to rebellion, anyway — don’t be surprised if their armies come a-calling. Be even less surprised if none of your allies come to your aid, because they might not fight to defend your unjust rule over someone else’s core. On the flip side, if someone else holds one of your cores, your own people could become so agitated that they might force you into a war you aren’t ready to fight. Cores can be added or lost on territories, but it takes sustained effort over a long time. And, yes, more than one country can hold a core on the same territory.

This is all very real-world stuff. Think of the permanently pissed-off French during the period from 1871 to 1914 when Germany held Alsace-Lorraine, agitating for another war with the new Reich. Further east, Poland, of course, considers Polish-speaking areas to be its core territories, but over the centuries various German, Austrian, and Russian kings thought they had the right to rule over those “poor, benighted” Poles. Real-world fighting over cores can be and has been centuries of struggle.

Cores are a simple concept, but tricky in practice, especially in places like Europe where many countries with many peoples rub shoulders so closely. Much of the Middle East has a different problem. Local cores are extremely localized and ancient, but national cores are weak or non-existent. All it takes is one small push — the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the Arab Spring in Syria — to rip a country apart, perhaps forever.

An even trickier real-world problem is that of core interests, and trickier still to model as a game mechanic. (It’s the core interests thing where most strategy games’ AI falls flat; you’re better off playing against human opponents.)

A few examples.

Britain didn’t fight Napoleonic France for 22 years because Napoleon was a bad guy (although he was). They did so because a united Europe, hostile to Britain, could threaten British sovereignty. Britain stayed almost entirely aloof from Continental affairs through the rest of the 19th century after Napoleon’s defeat, because no similar potential hegemon existed. When a new continental threat emerged, the Brits allied with those detested French against Germany (twice!) in the first half of the 20th century. And even though Britain’s stature was much diminished by the rise of American and Soviet power, the British Army of the Rhine stood watch over West Germany for the duration of the Cold War. Again, not because the Kremlin was ruled by bad men (although it was), but because the Soviets threatened to do what Hitler, the Kaiser, and Napoleon had threatened to do before them: Rule over all of Europe, and maybe even Britain herself.

The United States, with our globe-spanning, fuel-driven economy, has a core interest in keeping petroleum cheap and abundant. That’s why we got involved in the Middle East in the first place, and why we’ve never been able to extricate ourselves from the damn region. But the rise of fracking, especially in Texas and North Dakota, means that the geographic focus of our core oil interest is shifting away from the Straits of Hormuz. We still import about half of our oil, but an increasing portion of those imports is by economic choice, rather than physical necessity. If it’s cheaper to buy a barrel of oil from Kuwait than it is to extract it ourselves from the Permian, then it makes sense to do so. That’s a big change from the oil shocks of the ’70s, when American production (pre-fracking) stagnated, even as global prices quadrupled. With fracking, as the price of oil rises, we have the option to extract more domestically and buy less from overseas. Every time a new well comes online in North America, the wiggle room between us and the Mideast increases. We care less where the oil comes from, than that we can get to it cheaply and reliably.

However, as a global commodity, what happens to oil supplies in the Mideast can still threaten our economic security; it’s going to be a long time (if ever) before we can extricate ourselves fully.

But the lesson here is this: Allies change, regional focuses change, economics change, but interests, as Lord Palmerston noted, are eternal.

It’s safe to say then that when it comes to core interests, that for Iran, née Persia, not much has changed since the Persian Emperor Darius the Great began his campaign to subdue mainland Greece in 492 BC, and won’t change much in the future.

Or as Connolly put it on Twitter, “if the Mullahs disappeared tomorrow and the Shahs returned, they, too, would look at this map as a planning document and not as an historic artifact.” Persians have always looked at their “poor, benighted” Turkic and Arab neighbors in much the same way the Czars and Kaisers once looked at the Poles.

Another thing to consider before we get all regime-changey on Iran is the off chance that Islam might actually be a moderating influence on the country’s historically imperial ambitions. I know that seems impossible, given how frisky Tehran has been ever since the Islamists took over, but it isn’t an idea we should dismiss out of hand.

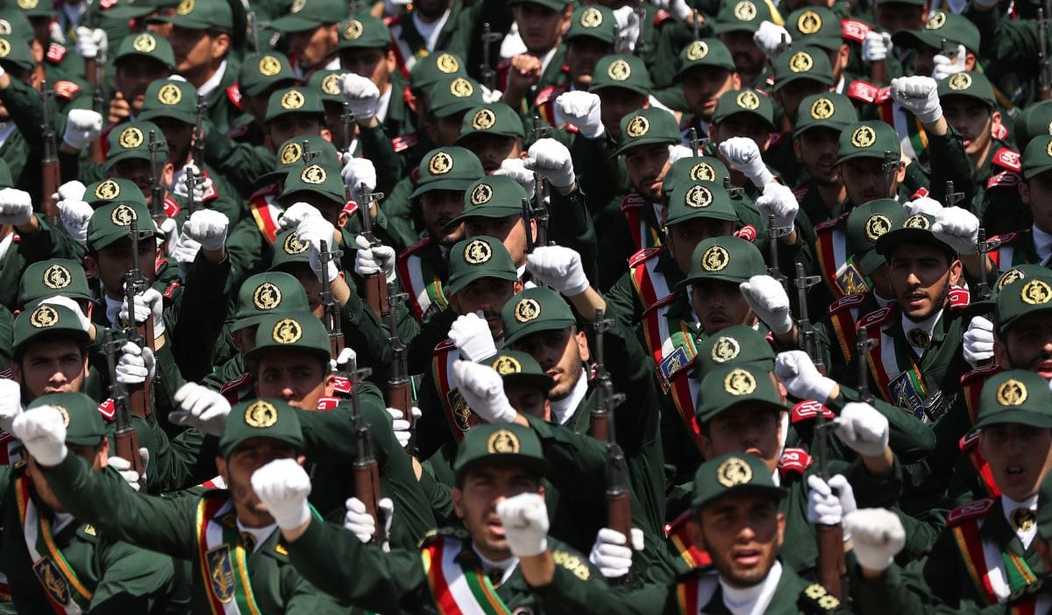

Unlike our previous hypothetical, where the mullahs’ regime just vanishes somehow, imagine instead an American-led multinational decapitation strike. Surely our Sunni Arab friends would be involved, at the very least providing airbases and logistical help. Once the dust cleared — presumably including the ashes of the Islamic Republic’s political and Revolutionary Guard leadership — the resulting surge in anti-American/anti-Arab nationalism might eventually present us with a regime even more difficult to contain than the current one. The Iranian people tend toward being pro-American, but that could change quickly if we screwed things up.

Indeed, as Austin Bay (IIRC) noted, a return to old-school Persian nationalism might also mean a resurgence in old-school Zoroastrianism. Fourteen centuries of Islam haven’t been enough to fully eradicate the old beliefs, and even after 40 years of the mullahs’ rule, Iran remains Persian First/Islamic Second. Religious-Ethno-Nationalism is a powerful “cocktail” (to lean on Austin Bay once more), and it could potentially whip the Persian people into the kind of militaristic frenzy the mullahs could never quite inspire.

Some future ultranationalist/Zoroastrian-influenced Neo-Persian Empire is most likely the stuff of dystopian sci-fi, of course, but it’s the kind of outcome, however unlikely, you would want an imaginative American leadership to give some thought to before undertaking a massive military action. But whatever replaces the mullahs’ regime, if we’re the ones who toppled it, likely won’t be much more inimical to our interests.

Our desired outcome then would be organic regime change, the kind that bubbles up from the streets rather than from the U.S. military raining death down from above. But we must also accept the fact that, especially after President Barack Obama dashed the hopes (and indirectly, the lives) of Iran’s last batch of revolutionaries ten years ago, that organic regime change might not come for a long time. We must plan accordingly, and for the long term. Unfortunately, that hasn’t usually been one of America’s strategic strengths. And given the increasing anti-American radicalism of the Democratic Party, we’re never more than one election away from caving more cravenly to the mullahs than even Obama dared.

With all that in mind, the course Trump has put us on is likely the best possible. Economic sanctions, combined with the implied threat of military action shrinks the “box” of actions available to the mullahs’ regime. If Tehran clangs against the side of the box too hard, more sanctions can be imposed, shrinking the box further. A few well-placed airstrikes on the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps infrastructure could shrink the box much more, albeit with higher attendant risks to the region and to ourselves. Already, Iran’s box is small enough that doing anything much more drastic than last weeks’ attacks risks alienating even their friends-of-convenience in Beijing. The current, patient course — allowing Tehran just enough room to keep losing friends and infuriating people — is the much-preferred one

We might — might — be witnessing the regime’s endgame already. As others have already noted, last week’s tanker and drone attacks look like the desperate actions of a government trying to provoke an American response. A response, that is, just big enough to generate a little extra domestic support for their unloved regime, but not enough to really hurt. That’s a fine line, especially given the precarious state of Tehran’s finances. Keep them in that box, and four more years of Trump could mean less than four more years for the rulers of the Islamic Republic.

And if not, there may well be a tolerable upper limit on mischief Tehran can cause, in the continuing absence of support from its people. In other words, a manageable situation rather than a problem in need of immediate solution.

Even so, there could come a time when the desperate mullahs pull a terrorist stunt so outrageous, so deadly, that we and some New Coalition of the Willing have no choice but to take forceful action on a regime-altering scale. But that time was not last week, it isn’t today, and if we stay the current course, then it may never come.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member