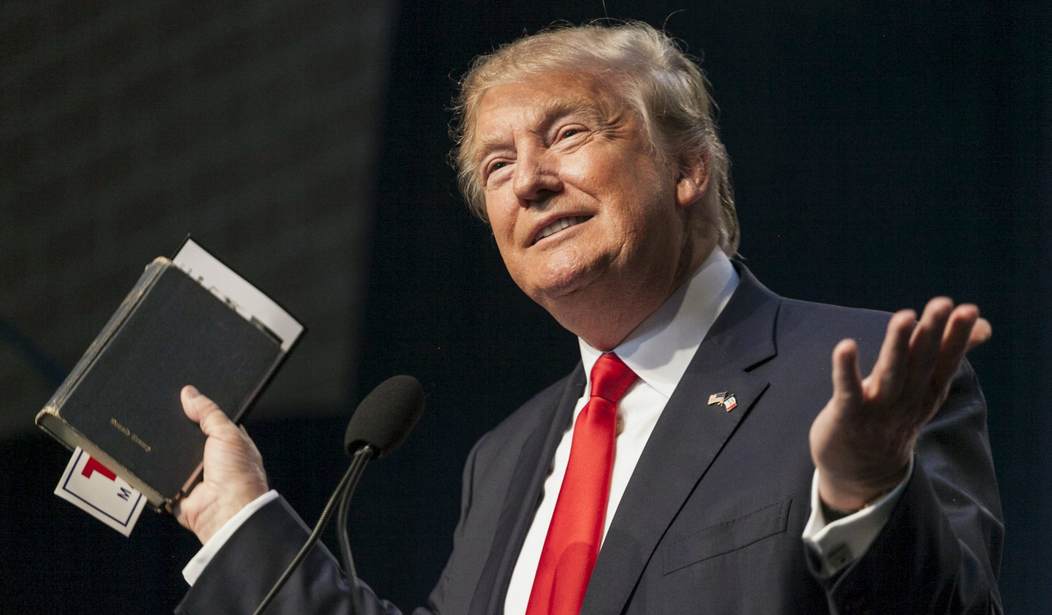

What motivates the Christian Right? Why, in particular, did cultural Christians overwhelmingly back Donald Trump in 2016? John Fea, an evangelical historian, presents rather un-Christian worldly motivations as the answer: fear, ambition, and nostalgia. In doing so, he paints evangelicals with too broad a brush and glosses over important concerns about Hillary Clinton, and the equally ungodly motivations behind her supporters.

“The evangelical road to Donald Trump has been marked by the politics of fear, power, and nostalgia,” Fea, professor of American history at Messiah College in Mechanicsburg, Pa., writes in “Believe Me: The Evangelical Road to Donald Trump.” Fea analyzes American history, drawing out the themes of fear, power, and nostalgia to argue that evangelicals were wrong to support Trump.

Fea has a powerful case. After all, Trump is a twice-divorced serial philanderer who infamously bragged about “grabbing” women and displayed unfettered pride and bravado. A group of “court evangelicals” came beside him and declared him a “baby Christian,” despite little evidence of true repentance. Christians should indeed struggle with the moral questions surrounding the 2016 election, and there were excellent reasons to reject Trump.

At the same time, Hillary Clinton represented a devious threat to traditional Christianity. While a lifelong Methodist, Clinton has often betrayed a terrifying animus against traditional Christian values. In a 2011 U.N. speech, she compared conservative opposition to the LGBT agenda to the heinous practices of honor killings, widow burning, and female genital mutilation. She has also vocally opposed religious freedom efforts, attacking them as enabling “discrimination.”

There is a widespread documented animus against conservative Christians in American culture, and Hillary Clinton represented that animus. Conservative Christians unwilling to choose a third party candidate found themselves torn between the Scylla of Donald Trump and the Charybdis of Hillary Clinton. Many chose to sacrifice their scruples for self-preservation.

Fea’s book refuses to acknowledge this horrible dilemma. Indeed, his deep dive into history does little to obscure his liberal slant.

The historian writes that “Obama had a strong record on a host of other issues regarding protection of vulnerable members of society — what might be called legitimate ‘life’ issues,” and faults “most conservative evangelicals” for overly focusing on abortion.

Fea also brings out the liberal bugbear of “dominionism” — a term almost no evangelical Christian knows but one frequently used by anti-conservative scare groups like the Southern Poverty Law Center to suggest that evangelical Christians have a plan to force their morality on the world. Fea himself once warned that Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas) represented a “dominionist” vision for America. Some radical sects may push for such “dominion,” but they are far outside the mainstream of evangelical Christianity.

Furthermore, throughout his discussion of the history of America’s Christian Right, Fea focuses on embarrassing moments and presents the story in as negative a light as possible. He notes the history of “white terror” and charges that evangelicals “did nothing to stop the violence wreaked by the Ku Klux Klan and the White Leagues,” while refusing to mention the 1990s efforts at racial reconciliation or the more recent movements among even the most conservative Christian denominations to vocally denounce racism.

Fea also smuggles in something utterly vile. After noting the horrendous twisting of scripture Christians in the South carried out to justify slavery — sometimes even cutting out every mention of freedom from the Bible before handing “slave Bibles” to their slaves — he compares that effort to the “fundamentalist” literal reading of scripture.

The historian sets the stage by noting that in the late 1800s, “the divine inspiration of the Bible … came under attack. German higher criticism — the belief that the Bible was not God-inspired and should be read and interpreted much like any other piece of literature — became ubiquitous,” he writes.

Responding to this Modernism, the “fundamentalists” “championed a literal, word-for-word, commonsense reading of Scripture, like the approach taken by proslavery evangelicals in the South.”

In these few pages, Fea has utterly undercut his authority as an evangelical Christian. Firstly, the Higher Criticism was far worse than just a suggestion of interpreting the Bible “like any other piece of literature.”

This movement actively cut up the first five books of the Bible — Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy — suggesting that they were written and compiled by multiple authors over centuries. Following this teaching, a scholar in The New York Times argued that Leviticus 18 — which clearly condemns homosexual behavior — was altered from a pro-homosexual original version. Neither this, nor the Higher Criticism, has one shred of archaeological evidence to support it.

More insidiously, Fea’s aside about “fundamentalists” adopting the Bible interpretation of pro-slavery arguments in the South is absurd and offensive. Ignoring clear statements against slavery (Philemon) and racial prejudice (Galatians 3:28), pro-slavery Christians in the American South gave the pseudoscientific racism of the time a Biblical backing by tracing Africans to the lineage of Ham, whom God cursed in Genesis 9.

This late innovation twisted scripture, and clearly went against many of the West’s Christian traditions. Not only did abolitionists in the North and England firmly oppose such nonsense — because of their plain reading of Bible — but medieval Europe also outlawed slavery under the Bible’s influence, and the scholastic school of Salamanca condemned the Spanish for enslaving native Americans, citing the Bible and Christian tradition.

Any evangelical Christian who knows his or her history must come away from John Fea’s book wondering whether John Fea really believes in the literal interpretation of the Bible, or if he prefers the Higher Criticism.

That said, “Believe Me” does provide an important — if one-sided — backstory for white evangelical fear, and it also provides an important caution about some of the “evangelicals” in Trump’s inner circle.

Fea critiques Robert Jeffress, the Texas megachurch pastor who seems at times to worship Donald Trump, and expertly nails the most treacherous aspect of Trump’s engagement with evangelical Christians — his support for the prosperity gospel.

The historian rightly cautions against Paula White, a megachurch “pastor” who preaches the anti-gospel of wealth, health, and victory. In 2007, she told her viewers that “anyone who tells you to deny yourself is from Satan,” despite Jesus’ clear and repeated teachings that any of His disciples must deny themselves (Mark 8:34-38). In 2016, White preached that as Jesus raised Lazarus, so her followers could overcome their difficulties if they would only “sow the seed of faith,” by giving $1,144 to her ministry…

Donald Trump first invited White to Trump Tower in 2002, and he later invited her to speak at his inauguration. Fea expertly notes that “the core beliefs of the prosperity gospel fit well with Trump’s personal creed of success, wealth, and ambition.”

In a similar vein, Fea attempts to discern what Trump meant by the slogan, “Make America Great Again,” and comes to the conclusion that the president “shows his inability to understand himself as part of a larger American story.” Trump’s apparent lack of humility while approaching the presidency “isn’t conservatism; it is progressive thinking at its worst.”

While Fea is far too harsh on Trump, I would have to agree with this painful assessment.

Finally, John Fea rightly warns Christians against turning America into a kind of “new Jerusalem,” identifying the United States with the people of God. Fea notes that the Christian tradition “teaches us to place our hope in the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.”

In the end, however, Fea’s criticism of pro-Trump evangelical Christians is both too harsh and too one-sided.

While Fea rightly acknowledges the many flaws of Hillary Clinton — her history with Benghazi, her “basket of deplorables” comments, her silence on religious liberty issues, and her “dumbfounding and incredibly stupid” decision not to court evangelical voters — he seems to upbraid conservative Christians for refusing to support her, as if this were morally culpable.

Fea makes no mention of Clinton’s own pride, her helping her husband silence women who accused him of abusing them, the apparent sense that she “deserved” the presidency because she would be the first woman, her own relentless pursuit of power, the Uranium One deal, and her unwillingness to admit the excesses of the Obama years.

Clinton effectively ran a culture war presidential campaign, blasting Trump’s supporters as “deplorables” due to their alleged sexism, racism, and homophobia. This was little better than the undercurrent of white identity politics that plagued the Trump campaign.

Many Christians saw the 2016 election as a sign of God’s wrath on America: conservative Christians had to choose between a man of suspect moral character who may defend their rights and a woman of suspect moral character who would attack them. It is possible the many evangelicals who chose Trump (less than the much-touted 81 percent but still significant) made the wrong decision, but that does not mean Clinton would have been the right one.

Evangelicals should struggle with these questions, but Fea’s book alienates them, rather than educating them.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member