Hello Refugees!, by Tuvia Tenenbom. Jewish Theater of New York; New York 2017. Paperback; 194 Pages. $12.99

Tuvia Tenenbom is the Jewish world’s answer to the late gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Diet Coke is Tenenbom’s drug of choice, to be sure, but the method is the same: Get in the middle of a dodgy and maybe dangerous situation and stir up a story that you then can write about. The faux-naiveté with which he accosts the unwitting actors in his improvised theater-of-the-absurd masks a deep cunning; an Israeli-born graduate of ultra-Orthodox religious education with advanced degrees in mathematics and computer science, Tenenbom can start trouble in five languages. Two of his books, Allein unter den Deutschen (alone among the Germans) and Allein unter den Juden (alone among the Jews), were bestsellers in Germany and Israel, respectively. The former first appeared in English under the awkward title I Sleep in Hitler’s Room in 2011, and my review was, to my knowledge, the first that the then-unknown author received.

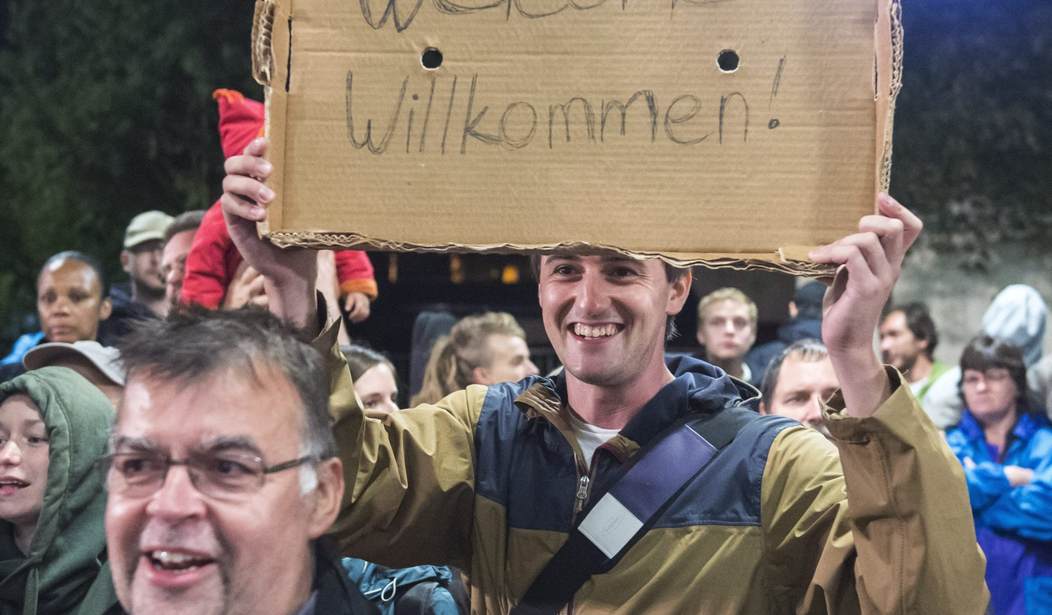

In the intervening six years Tenenbom has matured as a writer. If Kafka had written non-fiction, he could not have bested Tenenbom’s latest book. It is funny, sad, and frustrating to anyone who wants to make politics out of the European refugee crisis, at any part of the spectrum. This is his best work by far and one of the finest pieces of reporting I have seen in quite some time. Starting in 2016 Germany absorbed over a million migrants, many of them victims of the Syrian civil war but also economic migrants from all over the Islamic world. Germany’s long-serving Chancellor Angela Merkel declared, “Wir schaffen es!” (“We can do it!”) and Germany mobilized to demonstrate its good-heartedness and generosity—not so much to the world, but to itself.

Praised as an expression of German leadership and denounced as capitulation to Muslim invaders, the great migration is neither. In Tenenbom’s account, bored refugees eat bad food and contract skin rashes in the overcrowded, unsanitary facilities where the German government has dumped them. They are happy to complain to an Arabic-speaking journalist and spill their hopes and dreams—to marry a German blonde, to get rich, to get back to Syria or Afghanistan or Pakistan where they can find edible food. Most are just bored; a few are suicidal, but there is a one-year waiting list to see a German psychiatrist.

Pretending to be a German with a Jordanian mother, Tenenbom talks his way in Arabic into an airplane hangar at Berlin’s Tegel airport, divided into boxes filled with bunk beds. The heat is stifling and sanitary facilities are disgusting. He talks with a Syrian Christian who pretends to be Muslim to avoid beatings from his hangar-mates. He drives to a small town where a hotel for dogs has been converted into a refugee shelter, and the water runs a sickly yellow out of the faucet. He interviews a Syrian Palestinian who begs him, “Get me out of here.” He hates Germany and wants to go back to his wife and children in Syria. He meets disgruntled locals. One says, “They should go back home….They don’t integrate, they just walk here and steal things. They stole the bicycle of my friend. My girlfriend was raped.” When was this? “Ten years ago.” Were the refugees here then? “I don’t know.”

He interviews 25-year-old Ana, a German social worker specializing in sexual abuse of children, for example, rapes of teen-aged male refugees by other refugees in the overcrowded centers. “We tried to stabilize it, and not go deep into it,” she says. The boy was moved to another “container,” a block with a dozen rooms. “Is there any privacy?,” he asks. “No. No one would let German children in such camps.” Then why did Germany open its doors to the refugees? “I want to believe it’s because we’re good people,” Ana tells Tenenbom.

The story the refugees tell is silly, touching, absurd and distasteful by turns. The German politicians are surreally reasonable. Frauke Petry, the now-deposed leader of the right-wing Alternative für Deutschland, claims that she is in favor of admitting refugees, but not economic migrants, and that her party simply wants to help the refugees closer to Syria rather than on German territory. Gregor Gysi of Die Linke, the successor of the old East German Communist Party, admits that his party’s small following doesn’t like having the refugees there, either. Tenenbom asks him why Die Linke doesn’t demonstrate against Merkel. Gysi explains that if they did that, no-one would be able to tell the difference between the left and the far right. Nobody wants to look like Hitler, or even like someone who’s trying not to look like Hitler. It is a self-referential short circuit.

Gradually, it dawns on the reader that the German body politic wants to show that Germany really has changed, and that the Germans have become responsible world-citizens rather than nasty nationalists—but without the trouble and expense of caring for a million and a half new dependents. Many of the refugees came to abuse what they imagined was German generosity, and instead found overcrowded camps, awful food, scary sanitation and, worst of all, nothing at all to do. It is a grand burlesque of mutual deception in which neither side appears particularly good or evil, but rather confused and feckless.

Tenenbom asks innocent and obvious questions of public officials who duck and dodge to avoid him. The minister-president of the state of Lower Saxony promises to talk to Tenenbom after a press conference, but runs away to avoid questions about conditions in refugee camps. The mayor of Cologne, Henriette Reker, refuses to state what every German newspaper has reported, namely that migrants engaged in mass sexual assault on New Year’s Eve of 2015.

If public officials are feckless, private business is hilarious. “Integration” is the hinge concept in the refugee issue. Germany’s native working-age population is declining due to its low birth rate and the government justified the refugee influx on the grounds that Germany needs more workers. No-one appears to be working, though; at every refugee camp Tenenbom visits—out-of-commission ships, airline hangars, provincial hotels—the new arrivals have nothing to do.

Tenenbom contacts Daimler-Benz, which has a program to train refugees. The head of public relations sends a limousine to pick him up at his Stuttgart hotel; another Mercedes shuttles him to a factory with a showpiece integration program.

Here is the first refugee on the floor. His name, so he says, is Adhan and he is 26 years of age. He arrived in Germany in January 2014 and now he is an intern here…Watch, my dears, what Adhan is doing right now: Adhan screws the three-pointed star to the car hood. Yeah! This operation, the art of screwing, takes him two seconds. Ja! And he does it again and again; this is an assembly line, after all.

Adhan is the only refugee on the production line. And there is one more, sitting at a computer doing nothing in particular. And that is the entirely of Daimler’s integration program. It is grotesque, sad, and stupid.

Tenenbom’s previous books drew out German anti-Semitism, left-wing delusions and Palestinian paranoia in Israel, and American boorishness. Compared to the present volume, that was shooting fish in a barrel. “Hello Refugees” offers more subtlety and compassion: The Germans wanted to feel well about themselves, but end up feeling ridiculous; the migrants hoped for a new life under German sponsorship and find themselves utterly and hopelessly lost.

“Hello Refugees” was commissioned by the German publisher Suhrkamp. The English-language edition appears largely self-published. It deserves better treatment, including more thorough proof-reading.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member