Phony identities are a commonplace in cultural history. In musical history, the most remarkable example remains so-called Gregorian chant, as “rediscovered” through “source-critical” research by the Benedictine monks of Solesmes in the early 19th century. Reeling from the French Revolution which had nearly annihilated their order, the Benedictines sought an authentic medieval Catholic culture, the musical expression of a mythical Age of Faith, and thought they founded it by reconstructing an Ur-chant from the welter of different styles that infested ecclesiastical practice. It was all a scam, a hoax, a goof, as later scholars were to demonstrate, for example Katherine Bergeron in her 1998 study Decadent Enchantments, which I discussed here. Gregorian chant in the Solesmes theme-park version has such a strong association with Catholic worship, though, that many Catholics refuse to believe that they were scammed.

And so it is with Bob Dylan, parodist, satirist, scammer and snake-oil salesman par excellence. He never hid from us what he had in mind: he’s been playing with our heads since high school, finding the lever that loosened our tears, and our wallets. He caught a wave in the early 1960s with the folk revival movement, itself a hoax. We Americans are not a “folk,” not in the sense that Johann Gottfried Herder used the term. We do not have the deep memory of autochthonous roots that characterizes European cultures, the hand-me-downs of long-lost pagan experience. We are a people self-created by religious and political impulse. We have a distinct culture, but it is a self-created culture, a riff on Pilgrim’s Progress that became Poor Wayfaring Strangers, pilgrims pursuing freedom on a raft down the Mississippi, avenging Western gunmen, hard-boiled private eyes, and–yes–a young man in work shirt and jeans carrying a guitar. I tried to define what uniquely formed American culture earlier this year in a lecture at the Heritage Foundation, published by Tablet magazine here.

We are not a folk but a church, and our native music is church music–the Battle Hymn with its quotation of Isaiah 63, for example, or “The Year of Jubilo,” whose hymnal roots I analyzed here. Our popular poetic language is that of our national epic, the King James Bible. We sang the go-to-meeting songs of the Methodists and other Protestant denominations. This informed the spirituals of black slaves who gave us our first original art form. American folk music? Gospel is as close as we get to such a concept.

As I said in the Heritage lecture:

The peoples of the Old World, by contrast, recall a time before Christianity, when their woods and fields still were infested with the minor gods of the pagan world. That is Max Weber’s “enchanted world,” teeming with magical creature, remnants of the old folk-religions that survived the advent of Christianity. It is a world that knows only archetypes, but no characters. The Old World cultures are fixed in the past; their time is “once upon a time,” the amorphous time of legend. A day, a year and a life are indistinguishable: A traveler chances into a feast at an enchanted castle, and the seven days of his sojourn turn out to be seven years. Washington Irving repurposed the ancient tale: with an ironic masterstroke, he put Rip van Winkle to sleep in the Old World of legend and woke him up in the new time of the American Revolution. With this story, our first national writer declared independence from the literary sources of the Old World, and banished the enchanted world with the clear light of the new era.

The folk poetry of the peoples of Europe is lousy with magical creatures. It is the “enchanted ground” against which John Bunyan warned the Christian pilgrim in his 1678 tract Pilgrim’s Progress. The theme pervades Protestant culture in the early years of the American republic. Here is a version of the idea from an 1809 Methodist hymnal:

Good morning, brother traveler,

Pray tell to me your name:

What country you are traveling to;

Likewise from whence you came?

My name it is Bold Pilgrim

To Canaan I am bound,

I’m from the howling wilderness

And the enchanted ground.

I first heard it in Paul Robeson’s recording of “Joshua Fit the Battle of Jericho,” as an interpolated middle verse.

What passed for “folk music” in the 1940s and 1950s, by contrast, was the remnant of English ballad preserved in isolated Appalachian communities, as rediscovered by musicologists. Joan Baez made a specialty of such things. John and Alan Lomax gathered Appalachian music, African-American music, and other scraps and shards distant from the American mainstream as an expression of authentic “folk” culture. The entire “folk” movement was Stalinist through and through (including Woody Guthrie, who was a Communist Party hanger-on and probably a member. How do I know this? My late mother was Arlo’s nursery-school teacher in the Red Brooklyn of the 1940s).

Of course, it was all a put-on. Woody Guthrie was a middle-class lawyer’s son. Pete Seeger was the privileged child of classical musicians who decamped to Greenwich Village. The authenticity of the folk movement stank of greasepaint. But a generation of middle-class kids who, like Holden Caulfield, thought their parents “phony” gravitated to the folk movement. In 1957, Seeger was drunk and playing for pittances at Communist Party gatherings; that’s where I first met him, red nose and all. By the early 1960s he was a star again.

To Dylan’s credit, he knew it was a scam, and spent the first part of his career playing with our heads. He could do a credible imitation of the camp-meeting come-to-Jesus song (“When the Ship Comes In”) and meld pseudo-folk imagery with social-protest sensibility (“A Hard Rain is Gonna Fall”). But he knew it was all play with pop culture (“Lone Ranger and Tonto/Riding down the line/Fixin’ everybody’s troubles/Everybody’s ‘cept mine”). When he went electric at the Newport Festival to the hisses of the folk purists, he knew it was another kind of joke.

Dylan understood the biblical self-creation that stood at the heart of American culture, and how easily American devotion could turn silly. His first electric efforts produced what I still think his funniest line: “God said to Abraham: ‘Kill me a son’/Abe said, ‘Man, you must be puttin me on.'” Dylan was clever and insightful, but also lazy and contemptuous of his audience. One gem per song was enough, he seemed to think. The gems tend to be buried in the predictable filler that makes up most of his lyrics. The genre he chose was in part responsible: it was lampoon of a lampoon, a send-up of a mock-up.

Yes, Dylan used biblical imagery, e.g., in “All Along the Watchtower.” But to what effect did he use it? Julia Ward Howe made Isaiah’s image of the bloodstained God of vengeance trampling the nations in the wine vat ring true for our Great Generation–the Civil War, not the Second World War.

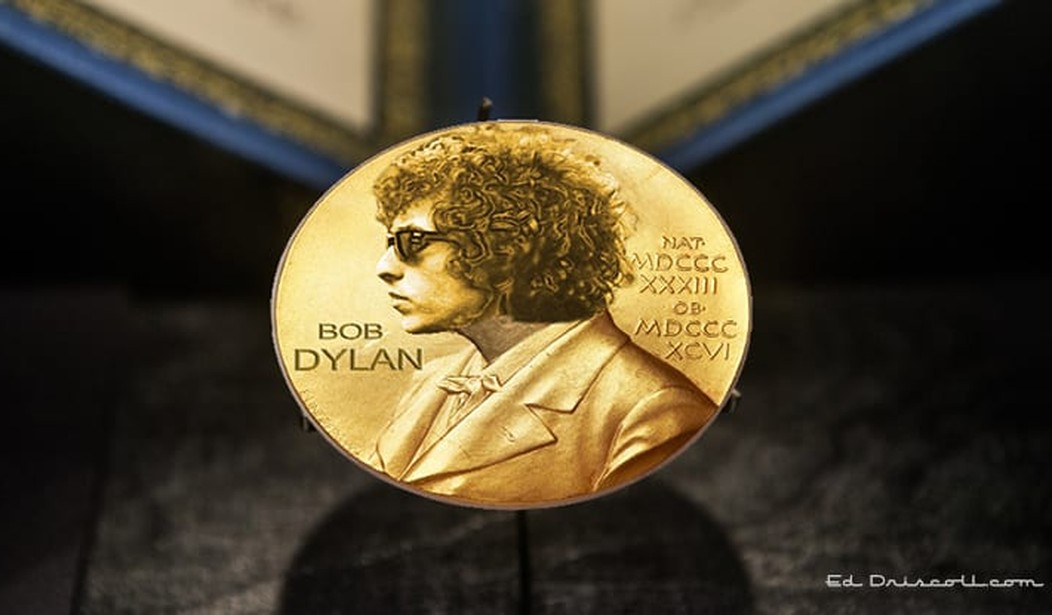

We have had first-rate poets: Robert Frost is our national poet, if we must choose. Dylan is a clever satirist, a maker of light verse, a jester who refuses to take us seriously. For that he deserves a modicum of credit (and for his refusal to acknowledge the insufferable stuffed shirts of the Swedish Academy, whom he takes seriously as little as he does his compatriots). To hell with the Swedes, who have always made the mistake of thinking they matter, for daring to instruct us regarding our own literary pantheon. The fact that anyone takes Dylan seriously as a poet is a gauge of our own cultural misery.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member