The conservative movement, and America as a nation, has lost one of its great intellectual and moral figures: Irving Kristol. Such is the respect and admiration for him that surprisingly, even The New York Times ran a first rate and warm obituary of him, written by one of its book review editors, Barry Gewen. His overview of Kristol’s life gives the reader as good a picture as one can get of his accomplishments and his way of looking at the world.

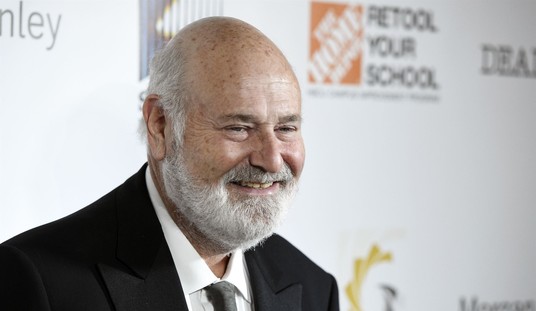

Irving’s smile and the twinkle in his eye, that is on display in the accompanying photo of Kristol receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President George W. Bush in 2002, is the expression that adorned Kristol’s face when he regularly met friends and associates. Whenever I met him for lunch or saw him when we attended conferences, he greeted me with that same expression. He was a man who loved seeing people, who went out of his way to help them and give them advice, who took great pleasure in the simple joys of life.

Most will remember Kristol, as all the obituaries note, as the godfather of neo-conservatism. My first memories of him, however, go back to the great debates of the 1950’s over McCarthyism and anti-communism. Irving was, one must say, among the first of the liberal anti-communists, and a fierce opponent of those who were determined that liberalism be anti anti-communist. In 1952, as some of the obituaries note, Kristol wrote an essay called “ ‘Civil Liberties’ 1952-A Study in Confusion.” He knew that Senator Joseph McCarthy was a “vulgar demagogue,” but what shocked people was his now famous comment: “For there is one thing that the American people know about Senator McCarthy; he, like them, is unequivocally anti-Communist. About the spokesman for American liberalism, they feel they know no such thing. And with some justification.”

It was a barb that stung. Decades later, in either the 1970’s or early 1980’s, I attended a forum in New York City held by Partisan Review, then still being published and edited by one of its original founders, the late William Phillips. Kristol was on a panel about the nature of liberalism in a new era. The panel turned into rounds of condemnation for Kristol for those words he wrote back in 1952. Irving quipped: “When I die, I fear that my comments on McCarthy will be the only thing I’ll be remembered for.” Fortunately, he lived long enough to know that would not be the case.

Years later, I explored the nature of the debate over McCarthy and anti-Communism in a long essay I wrote for PR. I found that Kristol also wrote a now forgotten but key document in the fight against the Stalinist mentality—the defense by most liberals of the Asian scholar Owen Lattimore, whom Senator McCarthy had stupidly called the major Soviet spy in America, “Alger Hiss’s boss,” he stated on the Senate floor. McCarthy had said he would “stand or fall” on this charge that Lattimore was “the top Soviet espionage agent in the United States.”

And fall he did, since no evidence existed at all to substantiate such nonsense. Later McCarthy backed down a bit, saying that at least Lattimore had a major role in the State Department, where he became the “ ‘architect’ of our Far Eastern policy” that according to McCarthy, resulted in China falling into the hands of Chairman Mao. This too was wrong, since Lattimore had but a peripheral role at State, as anyone who investigated the issue knew.

Yet, as Kristol emphasized, Lattimore was a major intellectual force and stood first and foremost among those scholars who sought to whitewash Chinese Communism. Irving took the time out to read the transcripts of Nevada Senator Pat McCarran’s Senate hearings into the Institute for Pacific Relations, the left-wing think tank of the day to which Lattimore was affiliated, as well as Lattimore’s testimony before a Senate committee chaired by Sen. Millard Tydings of Maryland.

He found in Lattimore’s own words that he regularly supported whatever position was advocated in foreign policy by the Soviet Union, and urged the U.S. Government to adopt a policy that would back Soviet efforts. He noted Lattimore’s proposal that all aid to Chiang-kai-shek be stopped unless his Nationalist regime agreed to form a coalition government in China with the Communists.

Agreeing that Lattimore “was no spy in the sense that Alger Hiss was,” and that McCarthy’s description of him “was irresponsible and wide of the mark,” Kristol argued that Lattimore was nevertheless an individual who posed a real danger to American policy. He was, Kristol wrote, a man transported “by the conviction of his own infinite innocence and righteousness.” Thus he saw Lattimore as the type of academic who translated Communist dogma into academic rhetoric, where it could not be deciphered easily. Thus, he knew enough not to describe Mao’s Communist troops as “agrarian reformers,” as some of the China hands called them–but rather referred to Mao’s headquarters in Yenan by “the more pompous, ‘dynamic popular government in North China’.” And he was so successful that his views became those of “the entire body of respectable opinion–conservative as well as liberal–on the Far East.” Thus “ingratiating pseudo-Marxist platitudes became the stock-in-trade of all the ‘experts’,” a modern trahison des clercs.Kristol’s words were so informed that even the late historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. cited them in essays and urged readers to study Kristol’s conclusions about Owen Lattimore.

Kristol, then as in later years, clearly differentiated the differences between liberals who sought to ally with Communists or to tolerate them, and those who understood they were America’s enemies. He even composed a list of prominent liberals who failed to understand the threat that faced our nation, and dared to name some of Washington’s favorite intellectual luminaries. As for Communists losing their jobs after refusing to answer the questions put to them by Red-hunting members of Congress, Kristol retorted that he had no pity for any liberal who wailed that Communists were “in danger of being excluded from well-paying jobs!” One could not forget that Communism was not just another idea, but was rather a “conspiracy to subvert every social and political order it does not dominate.” To tolerate Communists was thus to tolerate a conspiracy against the democratic polity. As Irving Kristol summed up: “So long as liberals agree with Senator McCarthy that the fate of communism involves the fate of liberalism and that we must choose between complete civil liberties for everyone and a disregard for civil liberties entirely, we shall make no progress except to chaos.” As for the defense of the rights of Communists to speak, Kristol had no objection, as long as liberals spoke as “one of us defending their liberties,” lest they be “taken as speaking as one of them.” The latter was a distinction most liberals of the day refused to make.

Irving Kristol continued through the decades to shed clarity on our nation while others once his allies lost their critical faculties. Decades later, his once ally Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. would praise Gorbachev alone for ending the Cold War, eschewing Ronald Reagan’s role, a mistake Kristol would never have made. And when Schlesinger returned from a trip to Cuba in the 1990s, he praised its dictator Fidel Castro as an authentic and noble leader, forgetting completely about Castro’s totalitarian rule, the huge numbers of political prisoners rotting in his jails, and his espousal of obsolete Leninist ideology.

In contrast, by then a firm neo-conservative, Irving Kristol continued to shed his light on the dangers facing his country, and the need to confront them honestly. We will miss his humor, his shrewd ability to get to the heart of an issue in short essays, and his moral compass. R.I.P.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member