How did the American colonists think of themselves 250 years ago? There had always been the idea among American colonists that they were different from the people who lived in the mother country, England, but it wasn't until the First Great Awakening of the 1730s that a singular American consciousness was implanted in their minds.

Evangelicals learned to defy traditional religious hierarchies and established churches to uphold personal convictions, which later prepared them to challenge political authorities.

The movement swept across all 13 colonies, creating one of the first truly "continental" shared experiences that crossed colonial boundaries.

The Seven Years' War ("French and Indian War") furthered the notion of American "otherness" when, at the beginning of the conflict, Benjamin Franklin proposed the Albany Plan of Union. Franklin suggested the colonies create a single government for defense, Indian relations, and managing new territories.

The colonial assemblies rejected it, and the British thought it "unnecessary." But the idea was out there and served as an example to colonists who met 20 years later to declare independence.

The seeds had been sown. But talking and thinking about independence were still largely individualistic endeavors. Few people were openly advocating for it. Even after Lexington and Concord, the Colonial Congress wanted to make nice with King George as long as he acknowledged their ability to govern themselves.

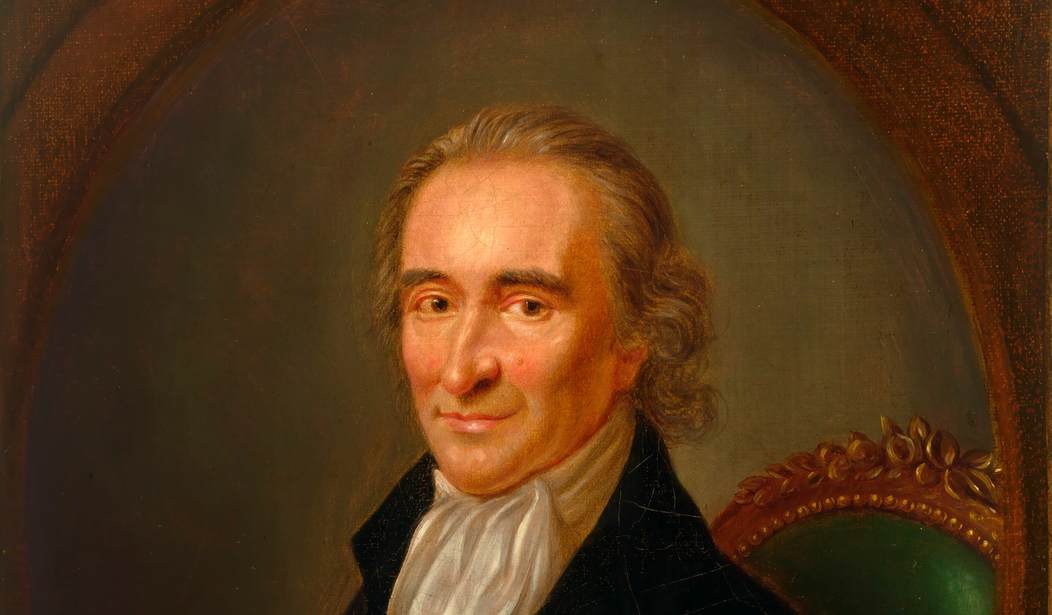

Along came Thomas Paine. He had no qualms about anything, much less talking about independence. He had already stirred the colonies with his pamphlet, The Crisis, where he assured his fellow colonials, "These are the times that try men's souls" following Washington's disastrous New York campaign.

Now, in late 1775, Paine was going to light a fire that wouldn't be extinguished until the British were defeated. He wrote Common Sense, a pamphlet that laid out, in Paine's plain-spoken style, the case for American independence. It was published on January 10, 1776, by printer Robert Bell in Philadelphia and was an overwhelming hit.

It's a shame that social media didn't exist in 1776. Positively, everyone was reading it. Copies were passed around families, churches, taverns, and anywhere people gathered.

The timing for the pamphlet could not have been better. Its publication coincided with the colonists learning that King George III had given a speech declaring that he himself believed independence to be their aim and promising “decisive exertions” to crush the rebellion. The news bolstered Paine’s larger point that the greatest danger lay not in breaking with Britain but in staying within a system that empowered a “royal brute” like George. Of the theory that kings had a hereditary right to rule, Paine had this to say: “Nature disapproves it, otherwise she would not so frequently turn it into ridicule, by giving mankind an ass for a lion.”

In some sense, Paine’s whole life refuted the notion that a man’s birth should dictate his place in society. Born to a corset maker in eastern England in 1737, Paine showed no more talent for that profession than he did during a stint as a tax collector on, of all things, breweries. When he arrived in Philadelphia in 1774, he had no obvious qualifications to become a magazine editor, save for letters of recommendation from Benjamin Franklin, who he had met in London. Nevertheless, as the new editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine, Paine expanded its readership with articles on topics ranging from the treatment of women to the conflict with Britain.

It was after the publication of Common Sense that colonists began to christen themselves "the Americans" in the revolutionary lexicon, redefining "America" as a country rather than just a collection of British provinces.

“Freedom hath been hunted round the globe. Asia and Africa have long expelled her. Europe regards her like a stranger, and England hath given her warning to depart,” Paine wrote. “O! Receive the fugitive, and prepare in time an asylum for mankind.”

A nation created in the minds of its people had never been seen before. Arguably, it hasn't been seen since. Paine's treatise placed the case for independence before the people in such a way as to "command assent," according to Jefferson. Washington had never spoken or written of independence prior to Common Sense. His biographer James Thomas Flexner notes that after he had read Common Sense, Washington called Paine’s arguments “unanswerable.”

An American consciousness would have emerged without Paine's essay, but it's doubtful it would have penetrated the colonies so swiftly and completely without Paine's rhetorical gifts and logical mind.

The new year promises to be one of the most pivotal in recent history. Midterm elections will determine if we continue to move forward or slide back into lawfare, impeachments, and the toleration of fraud.

PJ Media will give you all the information you need to understand the decisions that will be made this year. Insightful commentary and straight-on, no-BS news reporting have been our hallmarks since 2005.

Get 60% off your new VIP membership by using the code FIGHT. You won't regret it.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member