Muhammad Ali, the legendary boxer and self-proclaimed “The Greatest,” died in Arizona yesterday at the age of 74.

Ali had suffered from Parkinson’s disease for many years. But that didn’t slow his constant patter about himself when he gave interviews later in life.

Ali was a cultural icon and one of the most recognizable human beings in the world. But it was the controversy surrounding his refusal to be drafted and his conversion to the overtly racist Nation of Islam that defined his persona and ignited a generation of debate on war and race.

But ultimately, Ali was a fighter. And if controversy defined him, his athletic prowess is what made him a 20th century legend.

They were buffeted with the anger of the masses. It wasn’t an easy walk.

But Ali walked it loneliest of all.

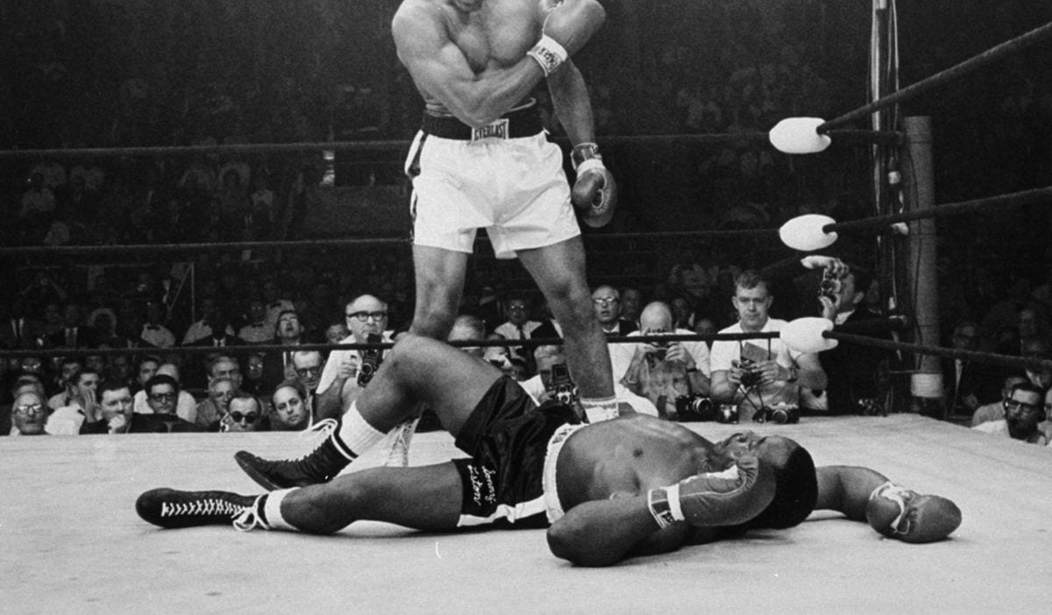

On the morning after his death, that is what we should remember most of all, more than the time he flattened Sonny Liston, then did it again. More than the three primal wars he fought with Joe Frazier, the time the two of them christened the new Madison Square Garden in 1971 and the time, four years later, when they nearly killed each other in Manila.

“Frazier quit just before I did,” Ali said that night. “I didn’t think I could fight any more.”

The writer Mark Kram summed it up thusly: “They fought for the championship of each other.”

All of that explains the basic source of Ali’s fame, as does the gold medal he won in Rome in 1960, as does the time, 17 years later, when he first lost and then regained the title from Leon Spinks. He became the most famous athlete in the world because of the speed of his hands and the ferocity of his punches and the strength of his sporting will.

But he became a worldwide icon for something else, something that wasn’t comfortable for people to talk about in the ’60s, something that didn’t easily fit on the sports pages of the day, where sporting heroes thanked God and drank milk and spoke of the red, white and blue. That wasn’t Ali’s way and it certainly wasn’t his destiny.

So he refused induction. He refused Vietnam. He gave up his title, surrendered hundreds of thousands of dollars, became a pariah, and a proud one, and never once flinched, not even when he was broke and people had stopped paying attention. He wouldn’t be ignored. He wouldn’t be forgotten. He paid a steep price for his beliefs.

And only then did he become what he truly wanted to be.

The Greatest. Of all time.

I question whether commitment to one’s beliefs in the face of hardship makes one “great.” Famous tyrants in history had a fanatical commitment to their beliefs and can by no means be considered “great.”

Beyond that, we can legitimately question where Ali got those beliefs. By the time of his refusal to enter the draft, Ali was under the thumb of the flim-flam man, Elijah Muhammad, who created the Nation of Islam in the 1930s as a con. The central racist tenet of the NoI is that white men are devils created by evil black scientists. You don’t read that very often today when Ali’s conversion to the NoI is mentioned, nor the black separatist philosophy of both Muhammad and current leader Louis Farrakhan.

His faith in that odious religion informed his beliefs on race in America as well. No doubt racism was a huge problem then and remains one today. But Ali’s extreme statements about how black people were treated in the U.S. exaggerated the problem to the point of near absurdity. Speaking out about racism of any kind was dangerous for blacks and everyone knew it. But telling half-truths about race in America was not a way to inform people or initiate change.

In later years, the rough edges of that debate were filed off and what remained was an image of a gentle man who preached peace and love around the world. Ali suffered for his beliefs and even if you believe him misguided, that is something to admire. He will certainly be remembered for his boxing skills as well as his over-the-top personality that, in many ways, defined an era of controversy and conflict in America.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member