Early on, I learned a lesson that likely saved my marriage. Like many young, newly married women, I had assumptions about what a good husband did. Despite my aversion to second-wave, sixties feminism, they were very second-wave ideas.

I was young and did not yet understand how much those ideas had become the baseline assumptions. Few thought about where the ideas came from. It was just how marriage was arranged. I expected perfect 50/50 chore allocation and separate bank accounts, but like many such women who had absorbed only the feminist lessons that gave choices to women but avoided any responsibility arising from those choices, I also wanted my husband to do the traditional breadwinner duty.

In short, my expectations ranged from logically conflicted to merely unfeasible. This made me a very discontented young wife.

One day, the morning after we scared our dog with a horrible fight about nothing, I lay in bed, wallowing in self pity because marriage was hard. I’d been the good girl. I’d done the right things. Marriage was supposed to be easy, the happy culmination to a slightly longer than expected Happily Ever After tale.

Looking back, I now see I was in mourning for the fantasy. Thanks to some wise mentors, the priest who married us, and two long married friends, I grew up that morning. I finally accepted responsibility. I would start worrying more about the kind of wife I was than the husband I had. I arose and started to do just that.

The change was instant. Three days later and anyone observing Jim and me would have thought that we’d always had a partnership marriage. (He’d moved to worrying more about the kind of husband he was the moment he said “I do.” My expectations were the block to our partnership and his steady faith in me was one of the reasons I got through it all.)

As a mother, I’ve put this lesson on repeat. Ask my children how often I say, “You worry about you,” or “The only behavior you can control is your own and I expect you to do so.” They can quote me with spot-on inflection.

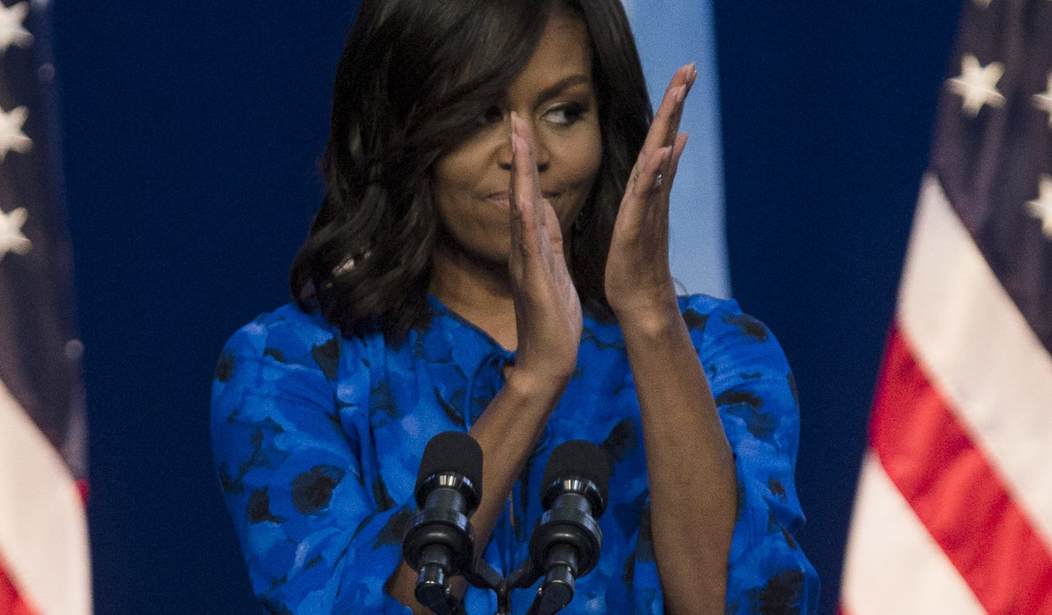

All of this came to mind last week. The White House Council for Women and Girls* put on the United State of Women Summit, a conference of “intersectional feminist evangelism.” For the feature event, Oprah Winfrey interviewed Michelle Obama. Keeping with the #HeForShe theme popular the past few years (turns out women do need men to help them succeed), Oprah asked the first lady how men can help women. “Be better,” she replied. “[B]e better husbands. Do the dishes. Don’t babysit your children. You don’t babysit your own children. Be engaged. Don’t just think going to work and coming home makes you a man.”

A few days later, Anne Marie Slaughter called on the same theme for her Father’s Day tweet:

Happy Father’s Day! Let us all commit to expect fathers to be equal caregivers & just as competent in the home as mothers are in the office.

— Anne-Marie Slaughter (@SlaughterAM) June 19, 2016

As advice goes, “be better” is not objectively bad. We should all strive to be better in our lives. But the context of the advice matters.

We women are lecturing men on how to be better fathers without regard for how we prevent them from doing so. When the first lady tells men not to babysit their children she seems unaware that often mothers or the family courts (after women initiate divorce proceedings) treat men as babysitters, or worse.

Slaughter has written on the need for women to allow men to participate as active fathers, so her Father’s Day tweet is particularly tone-deaf. “Be just as competent as…” drips with condescension, and judging from the reply thread, she did not anticipate the negative reaction.

Men are drowning in a sea of condescension, where women assume they do everything—and everything right—while men can’t do anything well enough.

*No, there isn’t a White House Council for Boys and Men. There is a commission to establish one but, who really cares about the boy crisis.

I think women miss their own arrogance because second wavers insisted that we focus on perfect ratios, like 50/50 chore allocation. Modern life is bound by measurement, as if something is not real unless we can chart it in a graph. Time and money make easy, convenient metrics. So we adjust standards for their measurability.

But the faulty assumption under the ratios does the real damage. We assume that mothers and fathers are interchangeable.

This is the mistake made in a Washington Post report on Republican and Democratic fathers. According to research, Democratic dads share chores more equally while Republican dads are more satisfied with their job performance. In explaining the difference, the authors do not consider that the satisfied dads might distinguish their roles as fathers from their wives’ roles as a mothers. Fathers impute different lessons and skills and provide a different type of security than mothers, which simple chore allocation surveys cannot catch. The red dads are not overly satisfied slacker mothers who happen to be fathers, but are satisfied fathers. (And their children’s lives are richer for their parents not assuming that parenthood is all about daily administration.)

“[I]f we women truly want equal partners in the home, then we can’t ask our husbands to be “equal” on our terms.” That’s Slaughter from 2013 in The Atlantic, writing on “The Immense Value of Giving Men Control of More Household Tasks.” And she’s right, even if she seems to have forgotten this insight.

When women tell men to be better, to be just as competent, it sounds like they are telling them to be women, which both showcases arrogance about women’s superiority and dooms men to failure as men will never be better at being women than women are.

Contrast all of this with Brad Wilcox’s suggestion to President Obama for his post-presidency life.

We should not be content with a world where a high degree of educational and economic inequality is locked in by fatherlessness. We should regard it as unacceptable that so many boys from poor and minority communities are growing up without dads. That’s why we should keep looking for new ways to revive the beleaguered fortunes of marriage and the ideal of committed fatherhood among poor and working-class Americans. One way is by communicating loudly and clearly that dads matter. No one will be better positioned, or have more credibility, than Barack Obama as he opens a new chapter in his life next year.

A father asking another father to support fatherhood culturally—that does not trigger arrogance sensors. I hope President Obama takes this advice when he leaves office. Fatherhood is broken, and our children are suffering for it.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member