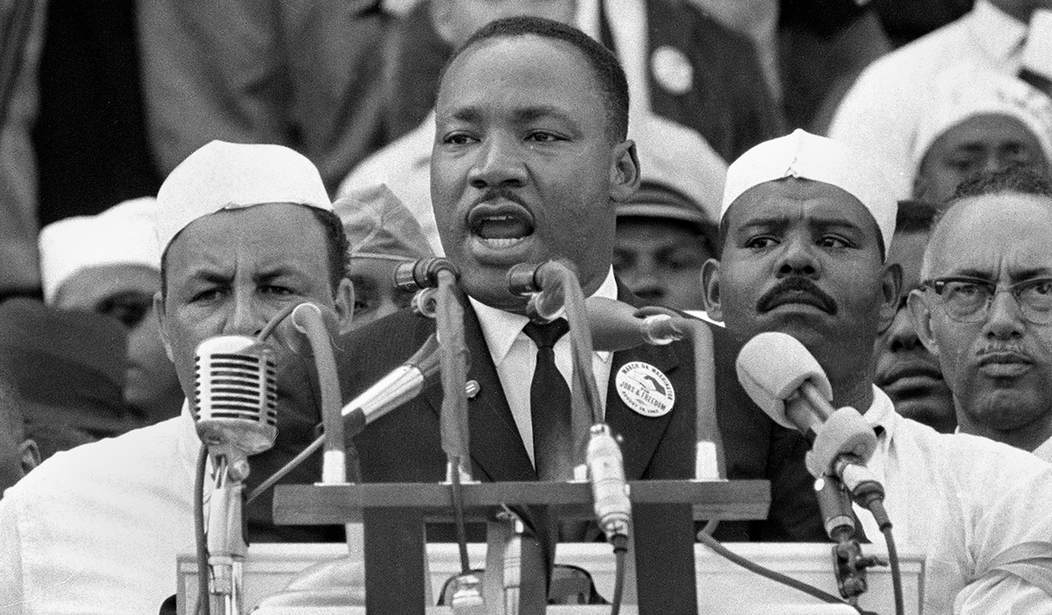

August 28, 1963, was a sweltering day in Washington, D.C. as most August days in D.C. tend to be. But this August 28 was going to go down in history because America’s finest orator was scheduled to give a speech.

Martin Luther King, Jr. was a preacher at the largest, most important church in Atlanta — Ebeneezer Baptist. He was also the leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference — the nation’s preeminent civil rights organization.

Standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial where 250,000 Americans had gathered, King began slowly — as all good orators do — reminding his listeners of the Emancipation Proclamation and its impact at the time on slaves.

But “100 years later,” exclaimed King, black Americans were still not free.

One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself in exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition. In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check.

It’s hard to explain the impact of that speech on many Americans, both black and white. And the reason it’s hard is that the conditions that existed for black Americans were unimaginably cruel and humiliating — even in the North. Most Americans today have no frame of reference to which to compare those times.

King’s “check” was the words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence that guaranteed all Americans — black and white — equality under the law. And despite the “check” coming back marked “insufficient funds,” “we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt.”

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. 1963 is not an end, but a beginning. Those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual.

King’s warnings against allowing violence and hatred to win is one of the speech’s most dramatic parts.

But there is something that I must say to my people who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice. In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred.

We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny.

Would that there were more leaders in the black community today who were strong enough, righteous enough, brave enough, smart enough to “conduct the struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline.”

Related: On Juneteenth, Many Black Americans Are Not Optimistic About Race Relations

This is why the speech is often thought of as the best American political speech of all time.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

So even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

There are a couple of things that all great speeches have in common. I wrote them down in 2008.

1.) The moment. The exact time in history when the speaker’s words will resonate.

2.) The backdrop. The place where the speech is delivered amplifies its meaning.

3.) The words. All great speeches are as inspiring when read as they are when delivered orally.

Think of the Gettysburg Address in that context. Or William Jennings Bryan’s “Cross of Gold” speech. Both of those speeches married the man and the moment to deliver an impact far beyond the words themselves.

Add King’s “I Have a Dream” Speech, with its thunder and lightning, biblical references, and a cadence almost martial in its beautiful repetition. You can trace the impact of that speech to the Civil Rights Act later that year and even the 1965 Voting Rights Act. While those pieces of legislation were flawed, they represent at least a partial fulfillment of King’s dream.

King’s dream represented the “promise of joy,” as Allen Drury referred to it. Not the absolute certainty of perfection that leftists seek; just the “promise” of a better life, a better world.

Striving for that is what King wanted us to do on that sweltering August day.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member