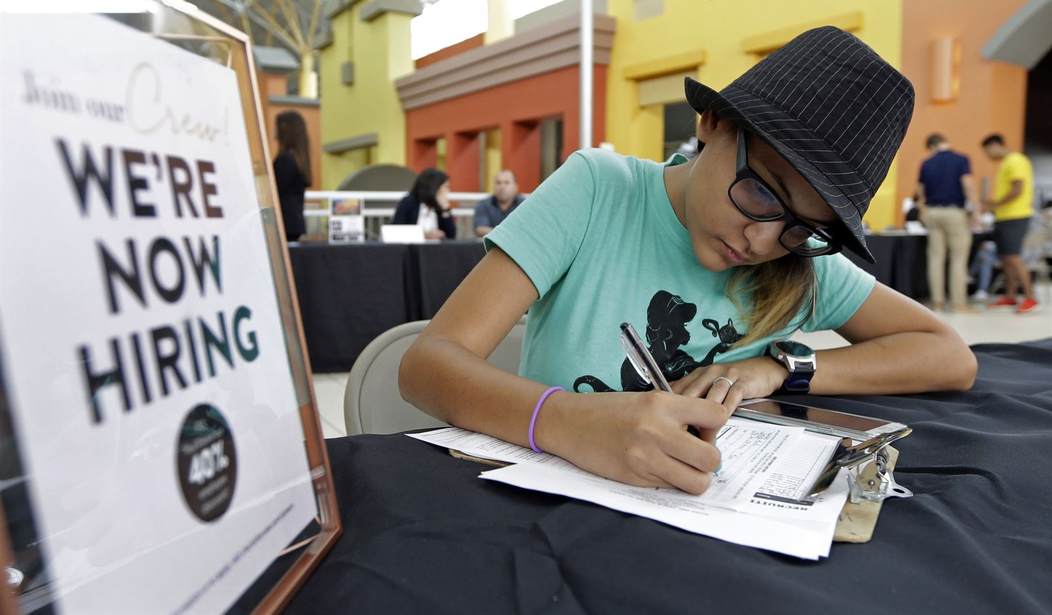

It’s a phenomenon that experts are having a hard time explaining. About 3.5 million women left the workforce in 2020 as a result of being laid off or losing their jobs during the pandemic. But only a fraction of those women has decided to return to their jobs or seriously look for another.

We know that many women were forced to take care of children because schools refused to reopen, and there’s evidence that some women are rethinking their career choices and considering alternatives. But it appears there’s a seismic shift occurring in attitudes toward work among women, and it may take a long time to sort out and become clear.

“A lot of women have left the labor force — the question is, how permanent will it be?” said Janet Currie, a professor of economics and public affairs at Princeton University and co-director of the Program on Families and Children at the National Bureau of Economic Research. “And if they’re going to come back, when will we see them come back? I don’t know the answers to any of that.”

Many economists and officials, including Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, had speculated that the re-opening of schools would free more mothers to take jobs. So far that hasn’t happened. The delta variant caused temporary school closings in many areas, which might have discouraged some mothers from returning to work in September. The number of mothers who were employed actually declined for a second straight month.

Related: The Real Reason the October Jobs Report Was So Good

According to the latest jobs report, 3 million fewer Americans worked in October compared to the beginning of the pandemic in 2020. And a major reason why women make up a large percentage of that workforce is affordable child care.

As the pandemic erupted in the spring of 2020, roughly 3.5 million mothers with school-age children either lost jobs, took leaves of absence or left the labor market altogether, according to an analysis by the Census Bureau.

A new report, “Women in the Workplace,” by the consulting firm McKinsey & Co. illustrates how the pandemic imposed an especially heavy toll on working women. It found that one in three women over the past year had thought about leaving their jobs or “downshifting” their careers. Early in the pandemic, by contrast, the study’s authors said, just one in four women had considered leaving.

Job “burn-out”, a phenomenon affecting women at a much higher rate than men, is also playing a role. “Forty-two percent of women said they felt burnt out this year, compared with 32% who said so in 2020. By contrast, a smaller proportion of men — 35% — felt burnt out this year, compared with 28% in 2020,” according to the AP.

A lot of women who say they’re burned out or considering other options can afford to do so because they have a spouse who works. But that’s not the case for millions of single mothers who work low-wage jobs.

Many other women can’t afford to be so choosey, even if they’d like to. Tens of millions of working women, many of them people of color, labor in low-wage jobs and struggle to afford rent, food, utilities and other necessities.

“There may be labor shortages, but lots of folks are working right now and do so because there is really no choice,” said Debra Lancaster, executive director for the Center for Women and Work at Rutgers University. “They need to work to put food on their table.”

About the only thing that can be said with any certainty is that women’s attitudes toward work are changing. Juggling priorities has always been especially challenging for women, and perhaps the pause imposed by the pandemic has allowed them a general rethinking of their role and what makes them happy.