Shortly after the Constitution was ratified in 1789, calls went out to convene another convention of the states to add amendments and rewrite entire sections. The effort never made it very far. In the last 231 years, there have been mini-boomlets to convene a convention of the states, independent of congressional approval.

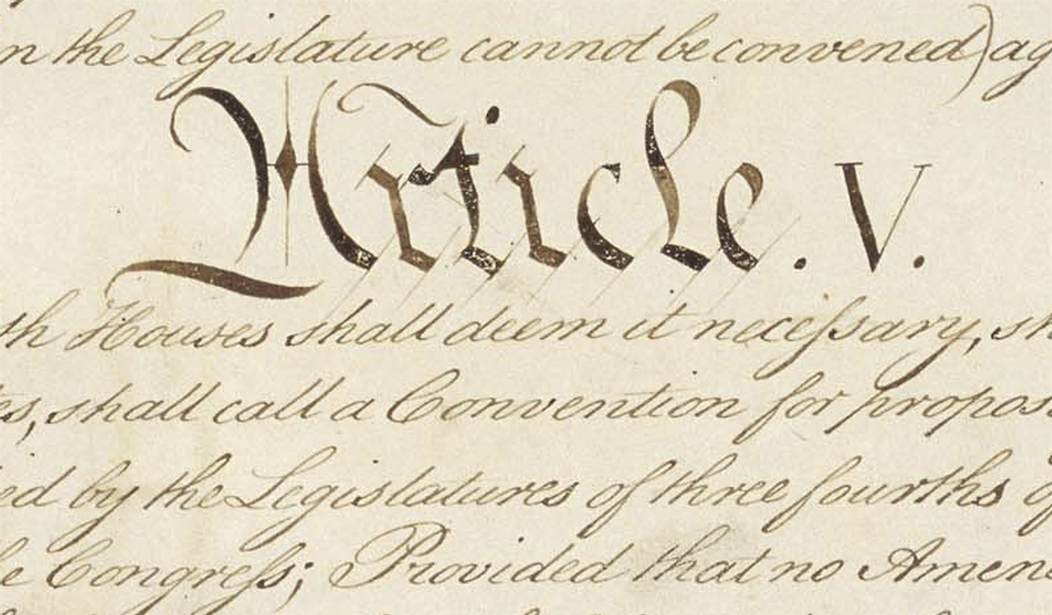

It’s known as an “Article V” convention and it would utilize the second constitutional device to amend our founding document. Article V allows for congressional passage of amendments that would then be sent to the states for ratification. Three-fifths of the states must approve in order for ratification to be successful.

But there’s another way to amend the Constitution. If 34 states approve a call for a constitutional convention, Congress must order one. This year, lawmakers in 42 states have introduced legislation that would do just that.

There was a mock convention held in Williamsburg, Va., in 2016 with about 100 state Republican lawmakers sitting down and ratifying six new amendments, including congressional term limits, and severe limits on the ability of the government to levy taxes and regulate industry.

Now, the leader of that 2016 effort, Mark Meckler, thinks its possible that if the GOP wins back control of the House and Senate in 2022, a second constitutional convention could become a reality.

“I think if [Republicans] win the midterm elections, if they take the House and Senate, they will try to call an Article V convention immediately,” said David Super, a Georgetown University law professor who has closely followed the movement for a new convention. “It’s not a foregone conclusion that the simple Republican majority would get there, but if they get big majorities, I think they’ll try.”

Those pushing for a balanced budget amendment believe they already have the requisite number of states. But there’s no uniformity in those convention requests with some specifically calling for a convention to consider a balanced budget amendment and others calling for a general conclave of the states. Until there is agreement, no convention is likely to be called,

There’s a question of what shape a constitutional convention might take. Would it try to be narrow in scope, focused on one or two issues? Even if that were the case, experts believe that the convention would pretty much be able to make its own rules and open the gathering up to wholesale changes in the document.

But it’s not clear they are right, nor that courts would agree. Since an Article V convention has never been called, the legal limits haven’t yet been meaningfully tested. And critics have long argued that there is no language in Article V to ensure its limited scope, or that a convention would necessarily follow the contours advocates lay out in their supposedly limited convention calls.

A broad convention, Super has argued, could possibly write its own rules or even change the existing ratification process, and courts aren’t likely to intervene. They may not even have the authority to do so. So there is an inherent risk of a “runaway convention” that goes beyond its purported aim and opens up the entire Constitution to an overhaul.

The first Constitutional Convention was held in secret. There were very few leaks as documents proposed during the convention were gathered up every night by the clerk. Delegates understood the vital importance of secrecy to prevent public pressure from stampeding them.

There is no chance that a second convention could be held in secret. If the attempt was made, every major press organ in the country would sue to prevent it. They would have an excellent case. A second convention would be the most important event of the 21st century and keeping the press out of it just won’t be possible.

Mucking around with the Constitution has always been a bad idea, fraught with unintended consequences. But the biggest argument against a second convention might be the ratification process. It won’t be possible to get 38 states to vote to ratify when all it would take would be one objectionable change or amendment to blow up any kind of consensus. The forces against ratification would be powerful, no matter what shape the new document took.

Consensus isn’t possible in America on any issue that would be debated at a constitutional convention. If we’re lucky, the convention would be subject to the same gridlock that Congress is experiencing.

If we’re not lucky, ratification fights could lead to violence and more division. It’s a bad idea and should be shelved.