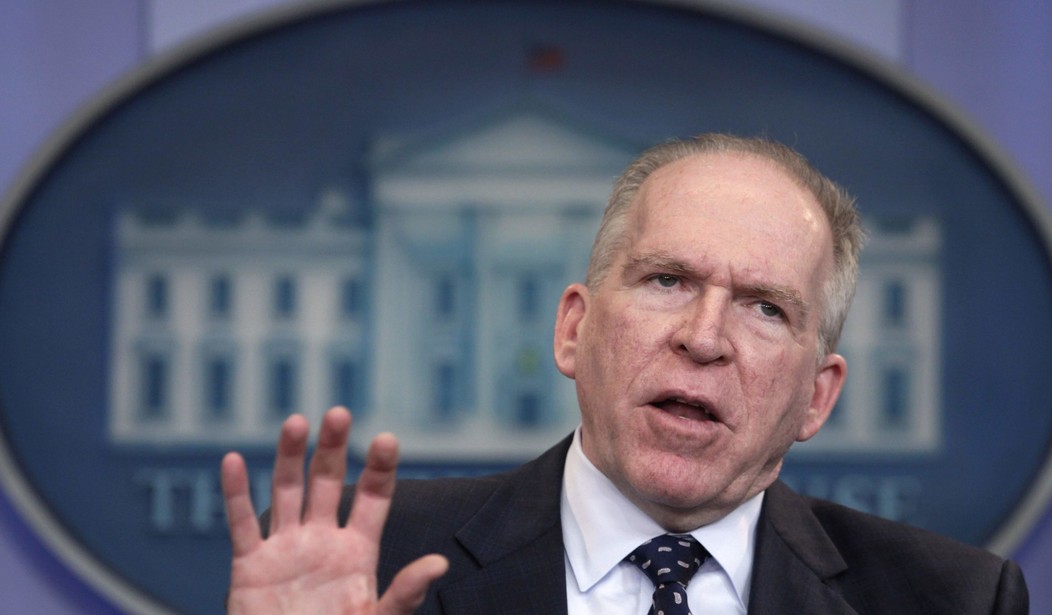

Why the rage at Trump for revoking former CIA director John Brennan’s security clearance? Why are so many former officials so adamant that his (and their) clearances should continue long after their “need to know”? I think it has to do primarily with working on projects that require clearances, or getting jobs with companies and universities that believe such people have rare and valuable insights into the world’s affairs.

The belief is greatly exaggerated.

Most people think that clearances provide access to real secrets, and that officials and ex-officials who routinely read secret and top-secret reports know a lot more about how the world really works than those of us who don’t. That is why corporations and news organizations like to hire people with clearances. They are mistaken, as I learned when I held high-level clearances. Indeed, I cannot think of many instances when these “real secrets” changed the way I thought about the world.

Undoubtedly there are important secrets that have been classified (mostly technical products such as satellite and drone photos or recordings of conversations or copies of texts or emails, and of course a very small quantity of documentation about ongoing operations), which gives those with access a competitive advantage in the job market over those who are not cleared. It also permits a few of them to spy on Americans without fear of reprisal. But the most valuable information I obtained at the State Department and the National Security Council in the early ’80s was not classified. Indeed, the most important came in the unusual form of Airgrams, those lightweight notes that traveled between continents by air mail at a low price. A cultural attaché at our embassy in Bonn, Germany, took his summer vacation in the East, and every so often mailed a report to the Department.

Secretary of State Haig was not given to reading such material, and he gave me—I was then special advisor to the secretary–a small pile of them. The Airgrams recounted the vacationing diplomat’s visits to several churches, where, on his account, a peace movement was blossoming. I selected a few and sent them down the hall, with a short note: “if this guy’s right, we’ve won.”

Those whose view of the strength and stability of the Soviet Empire, certainly the most important issue for American policy makers, depended on classified cables or CIA assessments had a very different take on East Germany. As late as a couple of years before the fall of the Wall, classified information described East Germany as one of the world’s top 10 economic powers. Yet we know now that it was a basket case. People with clearances, whose knowledge of world affairs depended primarily on reading classified cables, were not particularly well informed.

Classified information is often wrong, and those who depend on it are often misguided. The track record of our top intelligence and policy officials shows this clearly.

In 1985 I met secretly with representatives of the Israeli and Iranian governments, and read all the intelligence I could find. It was badly informed, as it had been at the time of the Islamic Revolution in 1978-79, and as it remained throughout the Obama years. I was not surprised when, a few years later, our entire network inside Iran was rolled up by the regime. Nor was I surprised when the CIA failed to appreciate the potential for revolution in Iran in 2009, or again in the past year. Nor was I surprised to learn, in recent weeks, that our network of agents in China was also rolled up. As a general rule, when a hostile nation identifies a network of American spies, it sends us disinformation through those channels, which are the ones read by officials with high clearances. This probably means that a lot of classified information is false, and our policy vis-à-vis Iran and China is based at least in part on rubbish.

There is no guarantee that access to secrets will enhance understanding. Richard Pipes and Robert Conquest did brilliantly without clearances, as did Samuel Huntington and as does Walter Laqueur. That is the sort of wise and knowledgeable person our top corporate officers and government officials should be consulting, Whether or not a failed CIA director gets continued access to presumed “real secrets” is beside the point.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member