by Jeremy Brown

There was an article in today’s New York Times that gives a vivid picture of the intensity of emotion among so many of the Iraqi exiles who have been voting in this Iraqi election. It has been heartening to see that the American mainstream press, it so far appears, is going to be covering this election:

SOUTHGATE, Mich., Jan. 28 – Ali Mohammed, who spent eight years in the Abu Ghraib prison in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, called the owner of the grocery store where he is a stock clerk before sunup on Friday to say he was putting on his best suit, the charcoal pinstripe he usually saves for weddings.

Glowing like proud papas, Mr. Mohammed and his supervisor, Hussain al-Jebori, cast the first ballots of their lives and lingered at the polling place here for three hours, clapping for friends and strangers and searching for familiar names, including a former cellmate, on the daunting list of 7,700 Iraqi legislative candidates. Mr. Mohammed, 39, said he decided on Friday to start a family, “because now my children’s future is secure.”

[…]

“I wanted to keep the paper in my hand for long time,” Mr. Jebori said. “First thing I imagined how much the paper cost us as a country and a people. It cost us a million people’s deaths. Now we get the victory, just now when we elect our representatives. I want to touch the victory. I didn’t want to leave it.”

My only quibble with this and a great many of the articles on this election is the use of the term “expatriates” both in the headline and, once, in the article. Though the term in its generic sense — it refers to any person who has left his or her homeland whether willingly or not — may be technically accurate, it is too evocative of Bohemian enclaves of artists and writers in search of inspiration. There is a point beyond which I think you have to use the word ‘exile.’ Thus, those German Jews with numbers on their arms that I saw as a child in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, were exiles. The millions of people from all over the world who have emigrated to the United States because they are afforded the freedom to live where they please, are expatriates.

“They decided to vote even if they die,” Diaa al-Tamimi, 35, said of his relatives remaining in Iraq. “There’s danger. But if not to vote, they’re going to die anyway. Election, that’s the best weapon for us. Terrorists, they use car bombs. We use the election.”

[…]

“It’s not safe, but they will do it,” Mr. Aljayashi said. “We spent our life as a number on paper. Now we count as a people, a citizenship. This is worth a lot. This is worth even dying for.”

[…]

No lapel stickers declared, “I voted today.” But voters displayed ink-stained fingers as a sign of progress.

“I’m very happy to show everybody my finger now,” Mr. Jeburi, the grocery owner, said. “I wish it could stay there for years and years.”

These people have been a living embodiment of the bitter reality of exile. Let’s save the word ‘expatriate’ for a time when Iraqis, as we are seeing the start of now, have the freedom to choose.

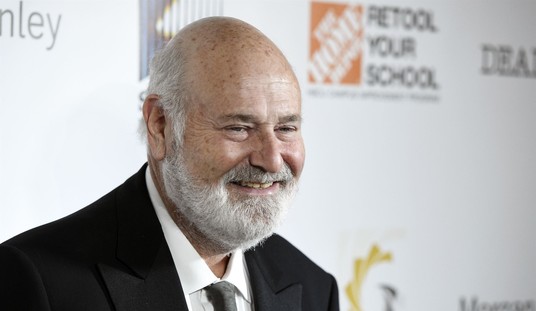

Mehsin al-Busaid, in tears, voting Friday in Southgate, Mich., in the election for 275 members of the new Iraqi national assembly. Mr. Busaid’s son was killed in the 1990-1991 uprising against Saddam Hussein. (photo by J. D. Pooley for The New York Times)

Join the conversation as a VIP Member