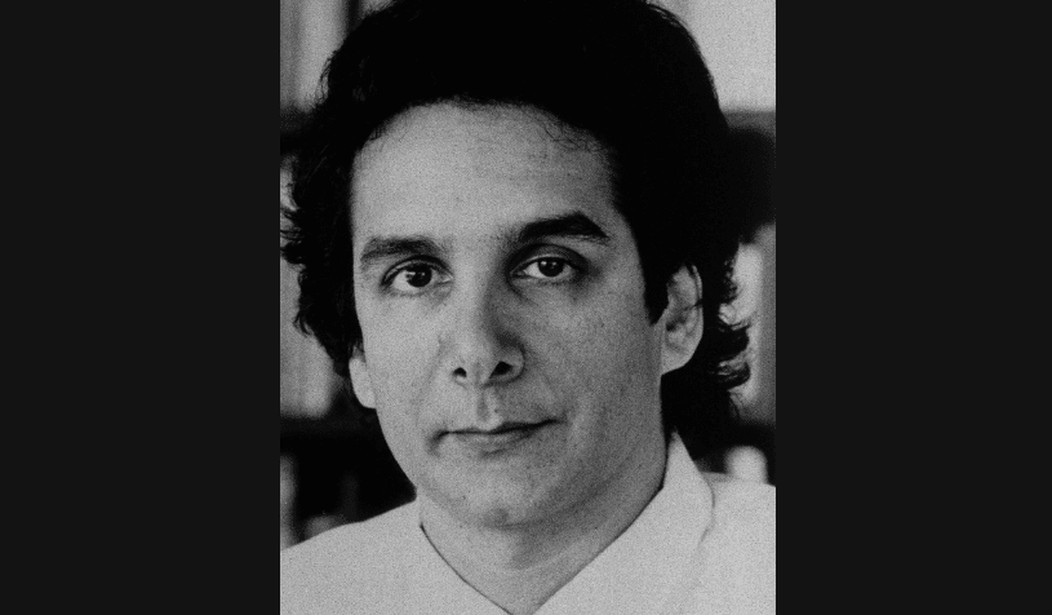

That Charles Krauthammer was an extraordinary oracle who enriched us all so remarkably is indisputable; what is sometimes lost is how it was ever thus.

When I first encountered Charles Krauthammer in the winter of 1967, he was already a local legend, having demolished the Québec-wide “Junior Matriculation” high school leaving exams. This was no small achievement; the province was then the most populous in Canada and Montréal rivaled Philadelphia for fourth-largest city on the continent. It was taken for granted no one would ever surpass the impossibly high 94% achieved years earlier by a young man named Chaim Goldberg, a product of the Protestant schools (as nearly all Jews were; public education was confessionally organized and Jews and Orthodox Christians were “Protestant” by law). No one, it seemed, had explained this to Charles Krauthammer, graduate of a small parochial Jewish high school, who recorded something over 97%. The communal pride was enormous.

Québec was then in the first throes of what would quickly grow into a violent confrontation between Francophone nationalists and the more economical and cohesive but self-destructively timid and reflexively apologetic Anglo community. Few people dared speak up for our rights and history. The flashpoint had become the McGill University campus, where a weak and groveling student government had withdrawn from the bilingual Federation of Students and joined the radical, ultra-leftist, unilingual Union Général des Etudiants de Québec. In this, they were supported by the powerful McGill Daily, the local version of the MSM, edited by a self-proclaimed Communist (an actual Party member), Patrick McFadden. I led a small group from the law school ready to brave accusations of racisme by demanding a plebiscite to reverse the decision and it fell to me to confront the Red Menace and his cavalier denunciation of “racist!” to any who dared challenge him.

So, on a particularly grey Montreal evening I headed to the offices of the Daily to debate McFadden, a loud, vicious man who relished destroying people with sickening (and invariably false) innuendo and name-calling. I arrived, having steeled myself for the much-awaited confrontation, to find the Daily offices crammed — and the debate already in progress. A tall, muscular, strikingly handsome young man was facing McFadden down and clearly had him (a permanent student probably in his 30s) befuddled.

“Who the hell is that?” I asked Arnie Aberman, an ally from the med school.

“Charlie Krauthammer.” (We all soon learned it was “Charles” not “Charlie.”)

“Get outta here! This is Krauthammer’s freshman year! He can’t be that good!”

But he was. It was a stunning performance. It wasn’t that Charles was breaking fresh ground — the issues on both sides of the Québec debate were well-known and already quite tired — it was the sheer elegance with which he presented his ideas, his extraordinary ability to parse McFadden’s platitudes and insults, turning them back on the man, reducing him to ultimately whining or shouting. But it was more than brilliant debating finesse; Charles was — as he would always be — in complete command of the facts, displaying the grasp of the history of the province and its linguistic strife going back to the conquest in 1759. The facts and figures of the economy, of the society, of the entire commonweal were at his fingertips, deftly presented in ways that gave substance to his argument and confidence to people who might otherwise be fearful of agreeing with him even though that was their intuition.

The most striking of all was his tone. In a time of deep bitterness and hatred, Charles’ voice was soft, and as he spoke of the constituent elements of this very complex world, he did so with a love and affection for all its people. While I led a movement dedicated to thrust and parry, to the zero-sum struggle of political survival, Charles was a voice of persuasion, of rational discourse, one that cleared the air of the acrid smoke slowly choking us all. While the rest of us debated to win, Charles wanted to convince.

And he was a freshman, for goodness’ sake! (By the time he was a senior, he would be editor-in-chief of the Daily.)

Not long after, we bumped into each other on Sherbrooke Street as an angry procession of French-Canadian student nationalists marched through the heart of English Montréal, chanting slogans both mean and demeaning, making it clear their vision for the future could never include people who thought as we did or spoke the language we used. Charles shook his head sadly.

“This is hopeless,” he murmured. “There’s no rational discussion to be had with people who reject reason because pumping up passions is easier for them.”

“Don’t be so sure,” I assured him. “I saw you in the lion’s den with McFadden. You have a vital voice that needs to be heard in this debate.”

“But this is not a debate. This is a contest in emotional manipulation. While I might learn to be good at that, it’s not a worthy life’s work.”

“Then what will you do?” I asked.

“Leave, I expect.”

And he did. We both did, like so many others. But what set Charles’ decision apart was his profound understanding of why he chose that course. Charles had a clarity most of us tried to avoid with other reasons for self-exile.

It would be some years before we met again, though I would occasionally get word of him. My time at Oxford University ended just before Charles came up, but my college (Trinity) and his (Balliol) sit cheek-by-jowl, and at an alumni weekend a Balliol professor, upon learning that I was from Montréal, asked if I “knew this Krauthammer chap.” According to the Don, Charles had decided to turn away from politics in favor of medicine at Harvard.

“Dreadful loss, simply dreadful” he mumbled.

I suggested my experience of Charles gave me to believe he knew best about himself and always made his own best choices.

“Perhaps that is true in most cases. But he has this extraordinary way of closing distances between ideas, getting to the root of things, making us a little cleverer than we might otherwise have been. Think how useful such a voice would be in the arena of worldly affairs and politics. No, no,” he declaimed with Oxonian certainty, “he may think he shall be a doctor, but let me assure you, the lure of reason and persuasion and argument will eventually call him back to the world of politics and debate. It’s where he belongs.”

It would be 15 years or more before Fred Barnes reconnected us. Fred was the managing editor of my PBS series, National Desk, and we turned to Charles to host whichever episodes took his fancy. He was exactly as I remembered: a man of great wit, commanding enormous breadth and depth of knowledge, dedicated to presenting the truth as he sought to persuade others with reason, a man who knew arguing passionately might satisfy himself but would likely fail in the more important job of demonstrating the substance of a rational approach. He was a man of character, a man of honor, and always, above all, a true gentleman in the best sense of that word, always respectful of those with whom he disagreed even when it saddened or even angered him. We became true friends, a treasure in my journey.

Though as the playwright Robert Anderson reminds us, “death ends a life but not a relationship,” the loss to those of us who knew and loved him is great; but the loss to our national conversation is almost too enormous to consider, at least at this moment.

We can only mourn his passing and, in a language he knew well, pray alla v’shalom: God grant him peace. And may He comfort Robyn and Daniel.

Let us cherish his memory; it may be a long time before we see his like again.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member