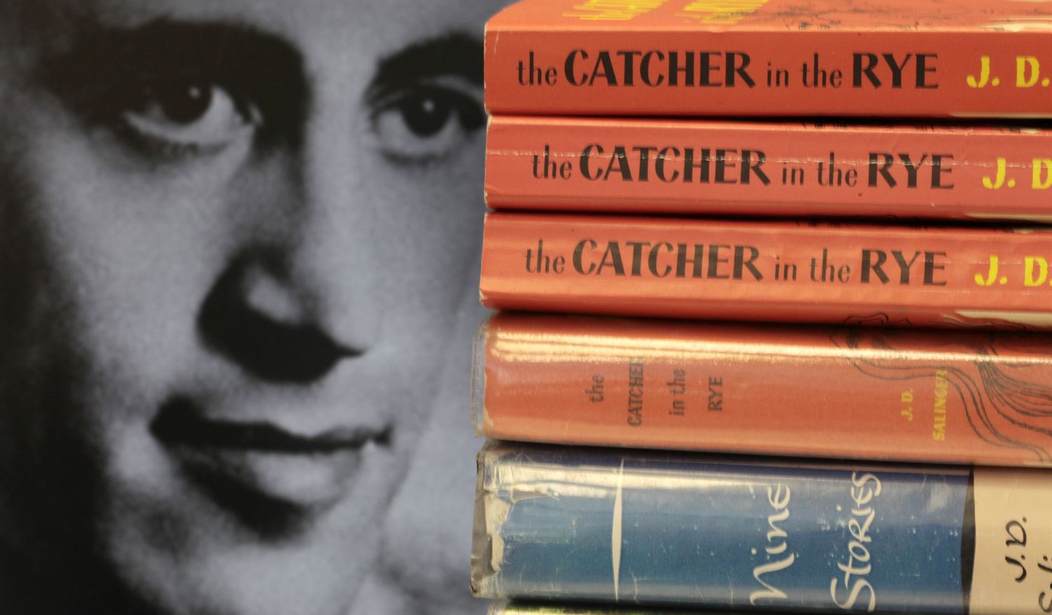

When I was in middle school, someone gave me a copy of "The Catcher in the Rye," which, depending on the national mood, has found itself on the banned list of various schools. The adventures of Holden Caulfield were interesting and entertaining. But more often than not, I found myself convulsed with laughter over Holden's observations about the world and the way in which he expressed them. I have often used the phrase "as sensitive as a toilet seat" to describe many people I have met.

Moreover, Holden's problems resonated with me. Many young people, and for that matter many adults, can relate to Holden's inability to conform to the unwritten laws, mores, and dictates that frame his world despite his immaturity and implied mental illness. And almost everyone at some point in their lives has felt the angst Holden experiences over the mercurial and often vicious nature of the world at large. Toward the end of the novel, Holden muses:

Somebody’d written “F**k you” on the wall. It drove me d**n near crazy. I thought how Phoebe and all the other little kids would see it, and how they’d wonder what the hell it meant, and then finally some dirty kid would tell them—all cockeyed, naturally—what it meant, and how they’d all think about it and maybe even worry about it for a couple of days. I kept wanting to kill whoever’d written it. I figured it was some perverty bum that’d sneaked in the school late at night to take a leak or something and then wrote it on the wall. I kept picturing myself catching him at it, and how I’d smash his head on the stone steps till he was good and g****m dead and bloody. But I knew, too, I wouldn’t have the guts to do it. I knew that. That made me even more depressed. I hardly even had the guts to rub it off the wall with my hand, if you want to know the truth. I was afraid some teacher would catch me rubbing it off and would think I’d written it. But I rubbed it out anyway, finally. Then I went on up to the principal’s office.

I went down by a different staircase, and I saw another “F**k you” on the wall. I tried to rub it off with my hand again, but this one was scratched on, with a knife or something. It wouldn’t come off. It’s hopeless, anyway. If you had a million years to do it in, you couldn’t rub out even half the “F**k you” signs in the world. It’s impossible.

Mark Twain's "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" has also found itself on the banned list across the nation, mainly for its frequent use of the n-word. Twain, of course, was writing in the vernacular of that region and time. But what so often goes overlooked is the moment in Chapter 31 when Huck is faced with the choice of either selling out his friend Jim, an escaped slave, to Miss Watson or helping Jim remain free.

It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a trembling, because I'd got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

'All right, then, I'll go to hell'— and tore it up.

Twain, through Huck, is challenging not only the social norms at the time but a particular religious worldview that provided justification and a set of apologetics for slavery. Twain knew it, and so did his readers. While some may shudder at Twain's use of the n-word, the book was an indictment of slavery, a fact that seems to be overlooked in this enlightened age. Of course, in this current age, the n-word might keep Twain's novel off of the school library shelves, while "The Catcher in the Rye" might be permitted if only for the language and one episode involving a prostitute and her pimp. Good books, even banned ones, allow or force us to wrestle with ideas, even those we may not like. Twain understood that. Salinger may or may not have written his book with that in mind, although there is plenty of material for discussion to be mined in "The Catcher in the Rye."

Of course, there are miles and miles of real estate between Twain and, for that matter, Salinger, and the books laden with prurient passages and graphic illustrations designed to stimulate libidos and trigger sexual inclinations among teens. But one might successfully argue that after students reach a certain age, books about CRT and DEI may be appropriate for discussion, provided they do not serve as tools for indoctrination. Of course, when parents have brought those issues up at their local school board meetings, they have been branded as heretical and anathema, and activists and the press decry efforts to ban books. Despite the keening of the left over the potential consignment of their favorite tomes to the literary outer darkness, it would appear that school districts have been curating the stacks of the local libraries to ensure that only the "right" books are available to their various student bodies.

Writing at The Free Press, James Fishback did a deep dive into the books that are available on the shelves of school libraries across the nation versus those that are not. Fishback writes:

So I decided to investigate just how one-sided things actually are. I surveyed the library catalogs of 35 of the largest public school districts in eight red states and six blue states, representing over 4,600 individual schools. All of these records are publicly available online. (Here are just three online catalogs I searched: Broward County, FL, Austin, TX, and Oklahoma City, OK.) What I discovered isn’t so much a problem of banned books. It’s that kids are often exposed to only one side of the story.

Fishback discovered that the number of books in school libraries promoting CRT/DEI and transgenderism far outstripped those of books offering an opposing point of view. For example, Ibram X. Kendi's "How to Be an Antiracist" was found in 42% of the libraries. "Woke Racism" by John McWhorter was found in one district's libraries. Fishback found that a book promoting transgenderism, called "Felix Ever After" by Kacen Callender, was available in 77% of the districts he researched. By contrast, he could not find a single school out of all of those he researched that offered a book with an opposing point of view.

By the Numbers:

Fishback found that out of 35 districts he investigated, these were the percentages offered in school libraries for the following conservative books:

- Nation of Victims, by Vivek Ramaswamy: 0%

- If You Want Something Done, by Nikki Haley: 0%

- Never Give an Inch, by Mike Pompeo: 0%

- America, a Redemption Story, by Tim Scott: 0%

- The Courage to Be Free, by Ron DeSantis: 0%

When Fishback researched the number of titles by well-known progressive authors offered in those districts, here is what he found:

- The Communist Manifesto (Karl Marx) — 75%

- Caste: The Origins of Our Discontent (Isabel Wilkerson) — 60%

- The 1619 Project (Nikole Hannah-Jones) — 54%

- Stamped (Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi) — 71%

- An African American and Latinx History of the U.S. (Paul Ortiz) — 40%

- The New Jim Crow (Michelle Alexander) — 60%

- Guide to Political Revolution (Bernie Sanders) — 40%

- White Fragility (Robin DiAngelo) — 54%

- So You Want to Talk About Race (Ijeoma Oluo) — 57%

- This Book Is Anti-Racist (Tiffany Jewell) — 45%

- White Rage (Carol Anderson) — 17%

When it came to books by famous people from the other side of the political and social aisle, the results were as follows:

- Capitalism and Freedom (Milton Friedman) — 8%

- Created Equal (Dr. Ben Carson) — 5%

- Woke Racism (John McWhorter) — 3%

- Breaking History (Jared Kushner) — 2%

- Social Justice Fallacies (Thomas Sowell) — 0%

- The War on the West (Douglas Murray) — 0%

- The 1619 Project: A Critique (Phillip W. Magness) — 0%

- The Case Against Impeaching Trump (Alan Dershowitz) — 0%

- Decades of Decadence (Marco Rubio) — 0%

- The Diversity Delusion (Heather Mac Donald) — 0%

- The Case for Trump (Victor Davis Hanson) — 0%

I'll see Fishback's school libraries and raise him one local public library. My library is awash in "woke" titles. Those books include Anderson's "White Rage" in English and Spanish. I cannot walk through the library and not see them. They are harder to miss than digital billboards. On the other hand, if I am looking for a book by a conservative author, fiction or otherwise, or even a "classic," I need a pith helmet, mosquito netting, a week's worth of supplies, an elephant gun, three sherpas, and a professional tracker just to find them. They are there, but it takes some dedication to locate them.

There is nothing wrong with exploring contradictory ideas in an age-appropriate setting. There is no reason students cannot read "Das Kapital" alongside "Wealth of Nations" or any book on economics by Thomas Sowell. Should "Mein Kampf" be an option? It might help students understand the mindset of the people of Nazi Germany, and that has driven college students and other malcontents across the nation and the world into the streets recently. But it should be countered by David Wistrich's "A Lethal Obsession," David Solway''s "Crossing The Jordan: On Islam, Judaism and the West," and Elie Wiesel's "Night."

It is a well-known fact that the Left projects. While its denizens wail and gnash their collective teeth over parental concerns about books that amount in some cases to pornography, it is conveniently memory-holing any volumes that present opposing or, dare we say it, diverse points of view.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member