Her name was Stephanie, “Steph.” She was on the tiny side of petite, beautiful, a classic pale-skinned freckled redhead with blue eyes who had recently divorced. A nurse, she was raising her two sons, 10 and 8 if I remember correctly. She lived in the far eastern part of Colorado, near the lowest point of the state, which coincidentally is adjacent to Mount Sunflower, the highest point in Kansas.

She had had a bad divorce, but life was looking up: she had a new mobile home for herself and the kids, she had just been promoted, and she had a new boyfriend. They weren’t — yet — officially engaged, but they were at the stage of talking about where to live and how to introduce him to the boys. She, a farm girl, wanted to live on a real farm and grow corn and wheat; he wanted to raise heritage cattle and sheep, burros, and peafowl.

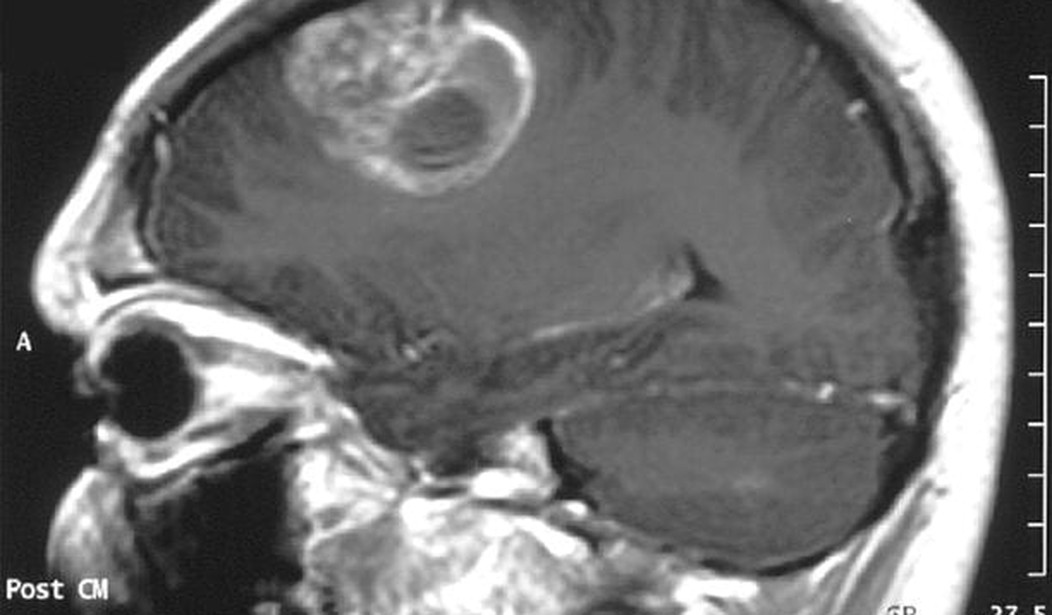

Until the day when she, walking down the hall in the hospital, had a terrible seizure. In minutes, she was no longer a supervising nurse, she was a patient. X-rays didn’t look good. That night she was in an ambulance to the University of Colorado Medical School in Denver, where imaging showed a suspicious mass. A biopsy followed: it was glioblastoma multiforme, often abbreviated GBM.

Median survival then was about a year, five-year survival 3-5 percent.

Her ex-husband moved into the new trailer and took care of Steph and the boys. Steph was treated aggressively and swore she would be the one to beat it, but aggressive treatment meant cutting a significant chunk of her brain out; they did their best. Then chemotherapy and radiation. Still, she declined rapidly.

I suppose by now you may have surmised that I was the new boyfriend. It was about ten months later I got the call. During my years at Duke Medical School, I’d heard people talk about how they hated a particular type of tumor and never really understood it. Now I did: I hate GBM.

So when Glenn linked this story, it very much interested me. A new treatment for GBM:

The cap, called the Optune, works by sending alternating, intermediate-frequency (200kHz) electrical fields into the brains of cancer patients. The idea is that the electrical fields disrupt cell division, preventing cells from properly lining up their chromosomes during a cellular split. This disruption, the company says, is fatal to cells. But because cancer cells make up the majority of the cells dividing in the brains of adult cancer patients, the treatment is more harmful to tumors than the brain.

This is really a wildly new approach to cancer treatment, a whole new modality. The results:

The median overall survival jumped from 16 months among patients on the standard chemotherapy to 21 months for those also using the Optune, researchers found. In the first two years, the Optune seemed to boost patient survival rates from 31 percent to 43 percent. At three years, survival went from 16 percent to 26 percent. And at four years, standard treatment patients had an 8 percent survival rate, while cap-wearers had a 20 percent rate. At five years, survival rates jumped from 5 to 13 percent.

Now, that may not seem like much, but for Steph and other GBM patients, it’s months of life they wouldn’t have had. Time to see your sons play high school baseball, maybe even enough to have seen them graduate from high school. Time to travel, or time with your family, time to walk through the pasture or do the work you love.

There hasn’t been much good news for GBM treatment since Steph was diagnosed. This is good news.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member