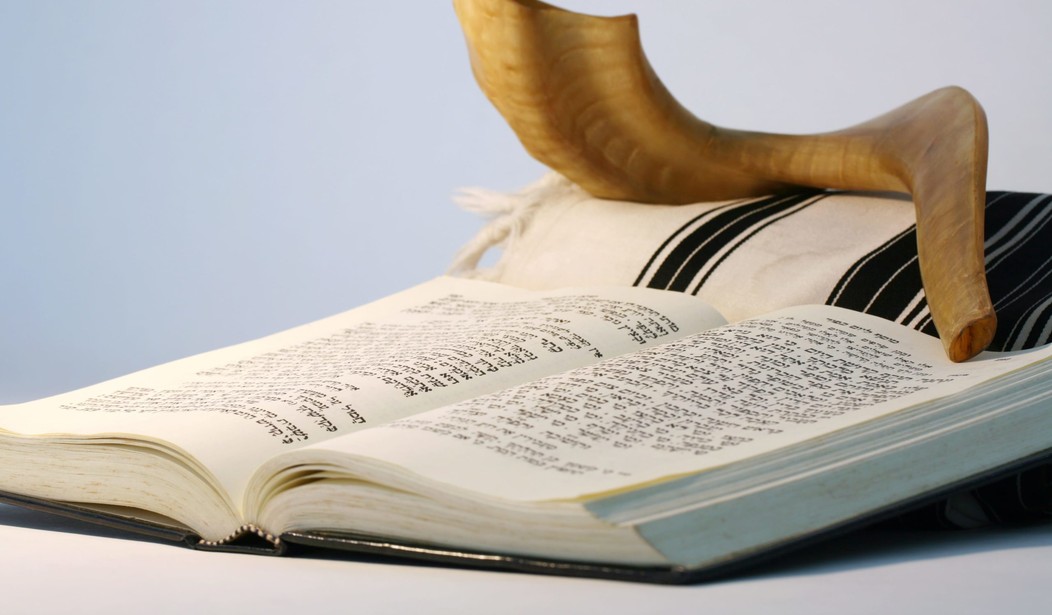

The structure of the service on Yom Kippur is constructed in such a fashion as to recall, as much as possible, the sevice as it was conducted in the Temple. Thus, everything evolves around the institution of the Këhunna, usually translated “priesthood.” The Torah reading for the day is the story of Nadav and Avihu (Leviticus X), at the very beginning of the institution; and the heart of the Musaf service in the afternoon is the complete accounting of the service as it is conducted when there is a Temple. It therefore seems fitting to explore what a kohén is and how he functions.

Parashath Emor (Leviticus XXI,1-XXIV,23) opens by detailing a number of mitzvoth which a kohén is to observe in order to preserve his unique sanctity among Israel, and summarizes: Vëqiddashto ki eth lechem Elo-heichem hu’ maqriv; qadosh yihye lëcha ki qadosh Ani Ha-Shem (“And you will sanctify him for the sacrifices your G-d’s bread; he will be holy to you for I, Ha-Shem, am holy;” XXI,8).

The sanctity of the kohén is so absolutely essential to Israel’s well-being (indeed to that of the world) that the Rabbis explain the emphasis laid on it by the initial verb in the above verse: “‘and you will sanctify him’ even against his will;” (Yëvamoth 88b). Born into his exalted status as a lineal descendant of Aharon, he can neither run from it nor deny it. And yet our verse strongly implies that his sanctity derives not from some inherent, intrinsic quality inherited from his illustrious ancestor, but rather from his function, “for your G-d’s bread he sacrifices.”

It is on this account that each individual member of the other tribes of Israel (as evidenced by the second-person singular pronouns in our verse) must “treat him in accordance with sanctity,” as Rashi summarizes the Talmud’s conclusion elsewhere (Gittin 59b).

“G-d’s bread?!” The incorporeal, omniscient, omnipotent L-rd of the universe eats food?! What does this really mean?

As has been noted many times by many different authorities, the general purpose of korbanoth is to establish a qurva, a closeness, between Ha-Shem, His nation, and the world. The last is crystal-clear from what we read elsewhere in Leviticus, that sacrificial animals must not have mumim (“blemishes”).

After providing a comprehensive list of conditions which qualify as mumim, the Torah states explicitly: Umiyad ben nochri lo taqrivu eth lechem Elo-heichem mikol élle… (“And from the hand of a foreigner, you will not sacrifice your G-d’s bread from all of these…” XXII,25). That is, foreigners, too, may bring korbanoth, but they must be of equal quality to those brought by Israel.

Korbanoth fall into five categories, of which three have a component which is burnt upon the altar and a component which is eaten by someone (either a kohén or the korban’s owners, depending on the class of korban), and two are burnt up completely on the altar with nothing being eaten. Those latter two are the ‘ola or ishe, so called because it is entirely raised up on the altar (‘ola) and burnt there (ishe, from ésh, “fire”), and the qëtoreth, or “incense.”

Concerning the ‘ola/ishe, G-d tells Moshe: Tzav eth bënei Yisra’él vë’amarta aléhem, eth qorbani lachmi lë’ishai réach nichochi tishmëru lëhaqriv li bëmo‘ado (“Command the bënei Yisra’él and say to them, My qorban, My bread, for My burnt offerings, My savory aroma, you will diligently sacrifice to Me at its appointed time;” Numbers XXVIII,2). There is that wording again: G-d eats bread? He has a chéch, a palate, with which to savor things?

We begin to get a glimmer of understanding from a comment made by Rabbi Avaham ben David (Ra’avad) on the Séfer Yëtzira. In discussing the metaphysical ramifications of the neural pathways connecting the human brain with the limbs and organs of the human body, the Ra’avad writes concerning the nose: “Behold, the chayya (animating angel, in this case of the sense of smell; cf. e.g. Ezekiel I,5ff. in which the prophet uses this term for an angelic being) sends a conduit to bring by means of it a réach nichoach for the réach is mixed with the air, and the vitality (chiyyuth) from the chayya’s potential runs back and forth along the conduit and is mixed with the chyyuth of the potential of the qëtoreth and is bound to the spirit of the living G-d which ‘hovers over the face of the waters’ (Genesis I,I,2)… and if one smells (yérach) the incense it is made good, and if not, Ha-Shem becomes wrathful (yichar Ha-Shem); therefore the qëtoreth nullifies wrath.”

Underlying every object and phenomenon in this world is a metaphysical reality captured in the letters of the word or phrase in the Holy Language which expresses that phenomenon; and the same group of letters retain a relationship even when their order is varied. It is in this way that tzaddiqim, the truly righteous, are sometimes able to effect the rectification of an evil decree, by bringing about a change in the order of the letters, which in turn effects a change in the mëtzi’uth, the perceived reality.

A case in point is made by the second Ozherover rebbe, the Birkath Tov, in parashat Noach. The decree of the Mabbul, which would wipe the Earth clean of life, constituted a time of tzarah, of woe. As the rebbe explains, Noach was obligated to meet the crisis by entering into hamqom hatzar – “the narrow place” of the téva – there to pray and perform his appointed service of caring for the animals, so that once gain G-d ratzah, “favored,” His creation. Each of these words – tzarah, hatzar, ratzah – is spelled with some permutation of the same three letters.

This is the process to which we allude, during this season, when we declare forcefully during this season, on Rosh haShana and Yom haKippurim, that tëshuva, tëfilla, utzëdaqa ma‘avirin eth roa‘ hagëzéra (“repentance, and prayer – which in our age, temporarily without a Temple, substitutes for korbanoth – and righteousness remove the evil of the decree”).

The Ra’avad’s comment is predicated upon a similar relationship between the words yérach – “he smells, scents” – and yichar, “he becomes wrathful,” both permutations of the same set of letters.

Just as mitigating the tzarah of the Mabbul required human action on the part of Noach, so does the mitigation of Divine wrath resulting from rebellious, libelous, embarrassing speech, for which the kappara, the “atonement,” requires the burning of incense, as we see, e.g. in the incident recorded in Numbers XVII,6-15, in which Aharon is able to bring a halt to a plague brought on by rebellious murmuring in the wake of G-d’s decisive quelling of Qorach’s revolt.

A common expression for wrath is the phrase charon af in which the first word is a noun derived ultimately from the primal root cheth-yud-réysh, connoting paleness, emptiness, desolation and (in the reduplicated form chirchér) “provoke”; the second word means “nose.”

The expression is particularly often employed for Divine wrath; to cite only some of the more obvious examples from the written Torah, cf. e.g. Exodus IV,14; Numbers XI,10; XII,9; XXII,22; XXV,3-4; XXXII,10, 13-14; Deuteronomy XXIX,26.

What has a nose to do with wrathfulness? The prescribed mitigation of the problem, as we see, involves establishing a réach nichoach, whether of incense or bunt offerings, as Moshe was instructed.

And, as the Ra’avad points out, the conduit through which the réach nichoach reaches Ha-Shem has an Earthly terminus with the noses of Israel; we must be there to inhale the aroma, the recognition of which passes though the human mind and soul and up the chain of the soul’s vast metaphysical structure to the kissé’ hakavod, the “throne of glory,” whence it was quarried.

If such an arrangement, under which our participation in the sevice of the korbanoth is so related with the sense of smell, it is surely equally so with the other senses (such as taste) which the Ra’avad goes on to entail. And all of these sacred functions require the këhunna. For this reason, the sanctity of the kohén is vital for Israel’s survival and well-being.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member