As I wrote a couple of weeks ago, Tom Cruise was wise to demand that Top Gun: Maverick appear on the big screen and not get lost as yet another nostalgic product on the Paramount+ streaming platform, where it would be just another sentimental memberberry:

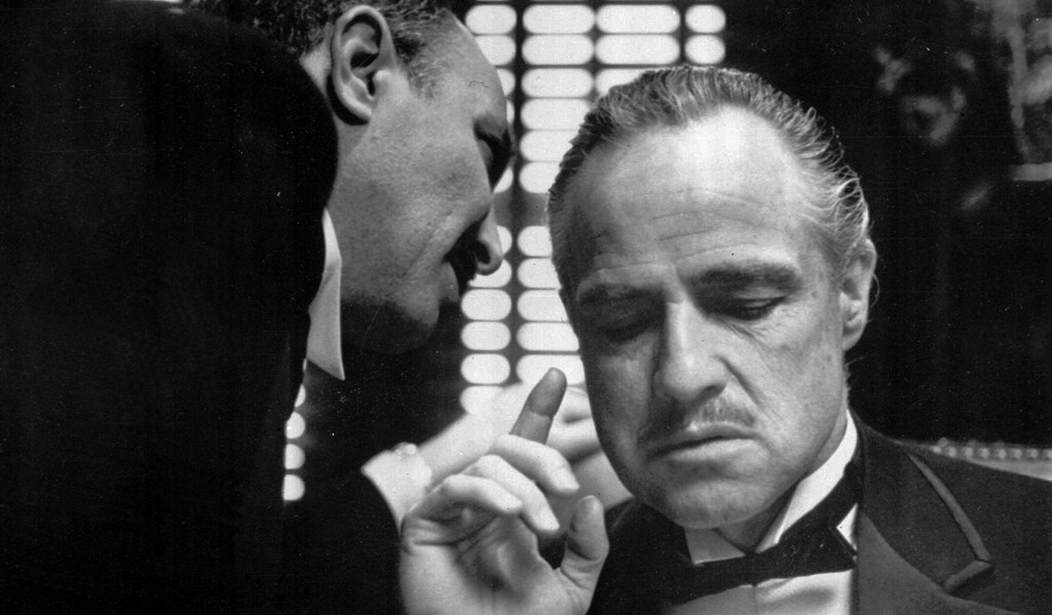

Paramount+’s memberberries take the form of their endless rebooted Star Trek series and its 2022 miniseries, The Offer, which does to Paramount’s first Godfather movie what shows such as Star Trek: Picard have done to their predecessors. The latter’s time travel-themed second season took two of the most beloved movies in the Star Trek franchise, Star Trek IV: The Voyage Home and Star Trek: First Contact, and turned them into a ten-episode nostalgic puree of their best moments.

Similarly, The Offer’s time machine takes arguably the greatest film ever made, and boils it down to a ten-episode making of series, a cross between Robert Evans’ classic documentary The Kid Stays in the Picture and a season of Mad Men, what with its period costumes, cars, smoking — and shot-on-the-studio-backlot production values. (Even The Offer’s theme song is highly reminiscent of Mad Men’s opening music.)

The Offer is also an example of the worst kind of Hollywood revisionism and score settling. When The Godfather was released as a novel, it was known as Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. When it became a movie, it was universally known as Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather. With a credit on the opening titles of “Based on Albert S. Ruddy’s experience of making The Godfather,” The Offer is an attempt by Ruddy, now 92, who is also listed as one of the executive producers of the new miniseries, to rejigger the iconic 1972 film as Albert S. Ruddy’s The Godfather.

Watching it, with Miles Teller as Ruddy, fresh off his performance as “Rooster” in Top Gun: Maverick, you will be asked to believe that only Al Ruddy was able to get Francis Ford Coppola to direct the film. Only Ruddy was able to deliver the definitive cast of Brando, Pacino, Caan, and Duvall. Only Ruddy was able to survive constant death threats and extortion attempts and keep the mob from wrecking its production. Only Ruddy was able to find a way to film in Sicily. In an article headlined, “‘The Offer’ Is a ‘Godfather’ Origin Story You Can 100-Percent Refuse,” Rolling Stone notes:

A subplot involving a failed relationship paints Al less as an inattentive partner than a man married to his work — he’s got his demons and can be utterly horrible to friends and lovers, but baby, he’s so good at his job! (Does this sound familiar, TV viewers?) It’s genuinely surprising that the credits don’t list Teller’s co-stars as “Ruddy’s Director,” “Ruddy’s Star,” “Ruddy’s Boss,” “Ruddy’s Girlfriend,” and “Ruddy’s Mob Buddy.” This isn’t just a print-the-legend look at film history. It’s a Ruddyography that turns a perfect storm of collaborators into supporting players in the making of The Ruddfather.

The last episode of The Offer spends as much time looking back at The Godfather’s star-studded premiere, attended by Evans, Ali MacGraw, and Henry Kissinger(!) as it does Ruddy birthing his next film, The Longest Yard, starring Burt Reynolds. Even The Offer’s Robert Evans says to the actor playing Ruddy, “Wait, you’re turning down The Godfather: Part II for a football movie?!” Ruddy tells him that this is what his gut is saying he’s got to do next. The heart wants what it wants, to coin a Woody Allen-ism. But this seems like serious Hollywood revisionism, given that for decades, Francis Ford Coppola has told interviewers that one of his demands for directing The Godfather: Part II is that Ruddy and Evans not be involved in its production. When asked about The Offer, Coppola, who had no involvement in its making, replied, “That’s the point of view of, I guess, the producer but it doesn’t really reflect what really happened, in my opinion.”

That’s a massive understatement. The San Francisco Chronicle wisely compares the miniseries to the sort of fictitious bio-pics that Hollywood once routinely churned out, such as The Glenn Miller Story and Night and Day, with Cary Grant as a highly whitewashed Cole Porter:

This goes to a larger issue: If a movie or TV show is supposedly based on true events, how factual does it need to be?

Studios of the 1940s and ’50s regularly made biopics that had nothing to do with the historical person’s actual life. That seems ridiculous now, but everyone has their own standard for how true a narrative needs to be. Here’s mine: If the whole point of watching something is to find out what really happened — if the story you’re telling derives its importance solely from its being true — then stick to the facts. Or at least try.

I imagine [Michael] Tolkin might feel differently, but that’s why he’s one of my favorite screenwriters: He’s a master at making stuff up. Just don’t watch “The Offer” if you want to know what actually happened.

In Deadline, Peter Bart, who served as Evans’ vice president for production, and originally optioned Mario Puzo’s The Godfather as a novel, writes, “While The Godfather’s dramatic saga over the years has moved millions of filmgoers, the TV narrative about its supposed production crises may ultimately be listed under the genre of science fiction.”

Early in The Offer, Miles Teller’s Ruddy flies to New York to pitch The Godfather to Charlie Bluhdorn (played by Burn Gorman), the Austrian owner of Gulf+Western, which had acquired Paramount in 1966, with rumored mob ties himself. After his secretary and Girl Friday Bettye McCartt, played by Juno Temple, advises Ruddy that Bluhdorn thinks in soundbites, Ruddy says, “Charlie, I want to make an ice-blue, terrifying movie about the people you love.”

Bluhdorn of course loves the idea, and we’re off. It’s difficult for The Offer to really build tension, when we know in advance that The Godfather will be made, who it will star, that will be shot as a postwar period piece in New York and Sicily, that it will clean up at first the box office and then the Academy Awards, and that Paramount will immediately green-light a sequel.

The Offer is bloated and cheesy, kept afloat primarily by the performances of Matthew Goode as Robert Evans and Dan Fogler as Coppola, who both eerily mimic the superstar Hollywood titans they’re portraying. (Goode, a British actor, really has Evans’ patented nasal ring-a-ding-ding hipster voice down cold.) Unlike The Godfather, where Coppola fought hard to actually shoot in New York and Sicily for the authenticity, according to IMDB, The Offer never left Hollywood, and it shows. The exterior of Los Angeles Center Studios, the former Unocal Oil Center building where Mad Men was filmed and which served as the lobby of Sterling Cooper’s Madison Avenue office tower, even doubles for Gulf+Western’s New York office lobby. (And likely its interiors as well, which also have a strong Mad Men vibe, albeit with more ‘70s-era greens and browns for a color palette.)

Take The Cannoli

In sharp contrast, Mark Seal’s Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli is a carefully researched, highly readable look back at the real history of The Godfather. As Seal told the Washington Times:

“With the 50th anniversary of the film looming, I felt it was the perfect time to expand the magazine story into a book — and continue my fixation with the film — and, in the course of additional research and interviews with Francis Ford Coppola, Al Pacino, James Caan and other members of the cast and crew, I was often surprised at what I found,” Mr. Seal explained. “I also delved into the massive trove of documentation about the movie, including Mario Puzo’s papers, now archived at Dartmouth University, and the minutes of the 1971 production meeting that Francis Coppola led with his creative team, each word recorded by a stenographer. It shows how the movie came to life.”

While The Offer depicts non-stop interference from the mob while Albert Ruddy, with a slight assist from Francis Ford Coppola and his crew, personally crafts The Godfather, Seal writes that once Ruddy met with Joe Colombo and his Italian-American Civil Rights League and cut the single use of the word “Mafia” out of the script — and cast several real-life wiseguys in various roles, he had surprisingly little interference from the mob:

Ruddy knew the word was only used a single time in the entire screenplay: when Tom Hagen visits movie producer Jack Woltz at his studio in Hollywood to persuade him to give Johnny Fontane a part in his new film, and Woltz snaps, “Johnny Fontane will never get that movie! I don’t care how many dago guinea wop greaseball Mafia goombahs come out of the woodwork!” It would be a simple excision for a world of cooperation.

“That’s okay with me, guys,” Ruddy said, and the producer and Joe Colombo shook hands.

* * * * * * * *

Having the cooperation of what he diplomatically called “syndicate men,” Ruddy told Ladies Home Journal in 1972, enabled the production to avoid a host of problems. “There would have been pickets, breakdowns, labor problems, cut cables, all kinds of things,” he said. “I don’t think anyone would have been physically hurt. But the picture simply could not have been made without their approval.”

After being reinstated as producer, Ruddy attended a $125-a-plate testimonial dinner for Colombo, who was being honored by the League for his humanitarianism. And the League itself now had more money than ever, thanks to The Godfather. The filmmakers paid the owners of apartments and bars and restaurants to allow the movie to be shot on their premises—but the bulk of the proceeds were said to have been handed over by the property owners to the League. “They gave a pittance to the owner of the establishment,” said Joe Coffey, the NYPD detective. “But the Mob got most of the money.”

Seal writes that the title of his book comes from one of the greatest ad-libs in movie history:

It all went like clockwork. Castellano as Clemenza stepping out of the car to take a leak. The prop pistol held by Rocco, the hit man, pointed at Gatto’s skull from the back seat. The three shots from the marksman resounding loud and blasting through the windshield. Clemenza momentarily looking up from his business to turn his head slightly. Gatto slumped over the wheel, dead.

Clemenza zips up his pants and returns to the car. And then Richard Castellano, with a decade of stage and screen experience under his big belt, says the line that Coppola had written for him in the script:

“Leave the gun.”

The gun, along with the corpse of Gatto, would be left behind as a warning sign to those who had double-crossed the Corleones—or might try to cross them in the future. “The Don’s justice is inevitable and complete,” wrote Coppola in his notebook. The two murderers prepare to leave the scene of the crime.

Then, without prompting from Puzo’s novel or Coppola’s script, Castellano remembers the command his wife had given him at home, and utters the ad-lib that would soon become famous:

“Take the cannoli.”

From the back seat of the car, Rocco, Clemenza’s “trouble-shooter,” retrieves a pristine little white bakery box, which Clemenza grabs by the strings in his fat hands.

There was no applause, not even a word of recognition on the set.

Perhaps nobody realized what had occurred until later: that Richard Castellano had just ad-libbed what would become one of the most quoted movie lines of all time:

“Leave the gun. Take the cannoli.”

It was the essence of everything: the wife, the kids, the fathers, the mothers, the kitchens, the families, and the food, always the food, and the extremes to which men had to go to put that food on the table. It was about the gun, yes, but it was more about the cannoli. It was about the statue in the distance with its back to the murder scene.

Above all, it was about the family.

“There is one reason that movie is successful and one reason only,” Al Ruddy observed decades later. “It may be the greatest family movie ever made.”

To that point, Mario Puzo’s son Anthony wrote of his father, “He believed that nobody had more family values than Italians. That’s why they were so good at being in the Mafia. What is The Godfather, he often said, but a heartwarming story about a family with great, solid family values?”

It really is an ice-blue, terrifying movie about people you love. But Mark Seal’s Leave the Gun, Take the Cannoli does a much more entertaining job of telling its story than the bloated, and often highly fictionalized ten-hour tale The Offer tries, and ultimately fails, to tell.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member