The death of at least nine concertgoers due to rapper Travis Scott’s 50,000 seater “Astroworld” concert in Houston on Friday, Nov. 5, is a reminder that large public events always contain the risk of severe danger. That danger is magnified when the lead singer has a history of making incendiary statements. Or as this Nov. 7 New York Post headline screams, “‘We want rage:’ A look into Travis Scott’s violent concert history.”

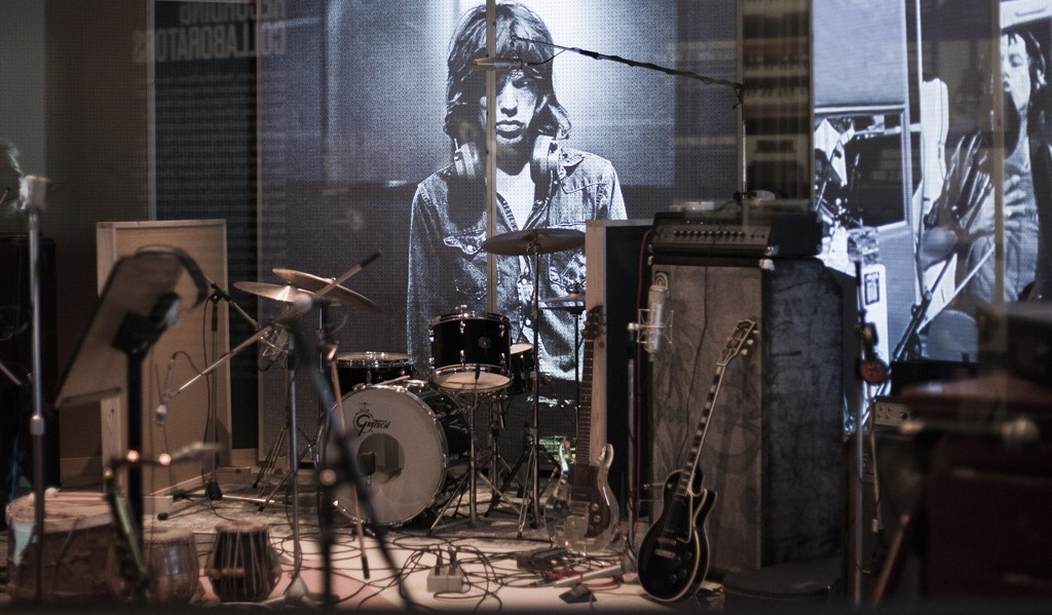

But the original concert where everything went terrifyingly wrong was the Rolling Stones’ infamous Altamont Speedway Concert on Dec. 6, 1969. Its horrors were shown to full effect in the Maysles Brothers’ legendary 1970 documentary, Gimme Shelter. But Gimme Shelter, with its surprisingly brisk 91-minute running time, merely captured impressions of the event, in-between the to-be-expected concert footage. It also used a distinctive editing technique, cutting throughout the film back to the Rolling Stones (primarily Mick Jagger and the late Charlie Watts) reacting to the events they’re shown by directors Albert and David Maysles on the Steenbeck editing console in the production company’s editing suite. In a 1971 interview, David Maysles said:

We wanted something to go beyond just the concert and the tour, and we were developing different themes. One of them had to do with filming the detectives and the Angels and some of the aftermath of the killing itself. That material was rather inconclusive because the trial was still going on, for one thing.

But as the film began to develop in the editing, we thought the most important thing was to keep it directly on the Stones’ experience. We would try somehow to involve them in how they felt about it. Charlotte Zwerin suggested the Steenbeck editing console as a device. The Stones hadn’t seen the material and when they asked to see it, it seemed like a good idea to film them reacting to the film rather than interviewing them, for example.

A lot of the material of Mick Jagger viewing the film did work out well, so we used it. After doing all that shooting we thought the film needed a much more simple line. Within that line the Stones had in some way to express their feelings about what happened. They don’t react with anything more than their expressions in a very simple fashion because they can’t explain it any more than we can.

Of course, their song ‘Gimme Shelter’ at the end of the film is a very eloquent expression of their feelings.

The cuts back to Jagger and Watts in the editing suite distance us from the horrors on screen by pushing us away from the action, or in the case of the Hells Angels’ brutal stabbing of African-American concertgoer Meredith Hunter, age 18, freezing the action to show that Hunter had pulled out a gun — possibly to shoot at one or more of the Angels — or to kill Jagger or another member of the Stones. The reactions of Watts, and in particular Jagger to the events they’re shown are surprisingly dispassionate — in Jagger’s case, likely because of the many impending lawsuits after the concert, in which three other people died, in addition to Hunter.

Would You Let Your Daughter Marry a Rolling Stone?

Like Travis Scott in 2021, by 1969, Mick Jagger and the Rolling Stones had built a career on a sense of danger and controversy. Their original manager, Andrew Loog Oldham, crafted their reputation as the anti-Beatles, and encouraged tabloid headlines like, “WOULD YOU LET YOUR DAUGHTER MARRY A ROLLING STONE?” The late Tom Wolfe quipped, “The Beatles want to hold your hand, but the Rolling Stones want to burn down your town!” In March of 1965, “Mick Jagger, Brian Jones, and Bill Wyman were fined five pounds each for urinating on the outer wall of a London gas station.” In 1967, Jagger and Richards were arrested for drug possession, and Brian Jones was similarly arrested the following year.

That was the year the Stones released their album Beggar’s Banquet, which kicked off with the song “Sympathy for the Devil.” The Stones’ original choice for its album cover was a disgusting-looking toilet whose rear wall was festooned with graffiti.

And yet, the Stones wanted to embrace the peace-and-love counterculture of San Francisco in 1969 as the climax to the concert film they were shooting that year. Why?

A Concert Night to Remember

Given that Gimme Shelter first played in cinemas in 1970, and then on the midnight movie circuit and the television late show throughout the 1970s, and was eventually released on DVD in 2000 as part of the Criterion Collection, its images have been seen by millions of rock fans. Those shots include the Hells Angels brandishing pool cues, threatening musicians — and punching Martin Balin of the Jefferson Airplane in the face, the numerous fat, naked people trying to shove their way near or onto the surprisingly low stage, the shots of people clearly out of their minds on the copious drugs (particularly LSD) available at the concert.

However, rock historian Joel Selvin’s 2016 book Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock’s Darkest Day, goes into infinitely more depth than the Maysles’ 91-minute documentary, to explain who first planted the seeds of a free concert in San Francisco headlined by the Rolling Stones, the logistics of the Stones’ 1969 tour, who the many of the people shown in the concert documentary actually were, and what later happened to them. Plus the financial and legal aftermath of the stillborn “free” concert.

Since Selvin knows anybody reading his book would have already seen the Maysles’ documentary, each paragraph reads like something out of A Night to Remember or The Last Days of Pompeii — you almost find yourself thinking as the Stones and their tour managers hash out the ideas for the concert, “Don’t do it, fellas — you’re gonna be really, really sorry!”

The Stones’ free concert in San Francisco was originally intended to be in Golden Gate Park. But, Selvin writes, “The Rolling Stones name only poisoned any possibility of using Golden Gate Park. As soon as the mayor’s office caught a whiff of the affair, the park was out of the question. Another site had to be found,” and plans were made to move the event to Sears Point Raceway. But as he adds, one of the most important details of Altamont that was left out of the Maysles’ documentary, was that Sears Point was then-owned by film and television production house Filmways, Inc. — and they demanded the movie rights to the concert, which Jagger refused:

Although they had been playing with the idea since before the tour began, even as late as four days before the concert, when the band was still recording in Alabama, there was still no site and yet plans went ahead. If Jagger had been willing to make a deal with Filmways to distribute the movie, the concert could have also taken place at Sears Point in Sonoma, where the large crowd could have been accommodated, the Hells Angels wouldn’t have been in control, and the staging was already in place, but he wouldn’t consider giving up movie profits from a distribution deal. Jagger was going to make this concert happen, no matter what, and maintain his arm’s-distance control. So he was willing instead to risk everything on a desperate last-minute move to some oil blotch on the far edge of the San Francisco Bay Area with no police, infrastructure, or medical provisions, a decision that would prove disastrous.”

A big reason Jagger didn’t want to give up film revenue to Filmways is that by 1969, the Stones were effectively broke, thanks to a dreadful contract they signed with Allen Klein in 1966. Jagger eventually found an outside financial advisor, who recommended touring and other sources of revenue that were outside Klein’s purview as the band’s attorneys began to disengage the group’s finances from Klein’s control. When Jagger learned that a documentary film about Woodstock was in the works, he wanted to have a film that would hopefully beat it to the punch, and end with an outdoor concert that would equal or top Woodstock. As Selvin writes:

Jagger wanted to cultivate the underground; being considered cool by cognoscenti was new for the Stones. He was coming to San Francisco for a coronation.

This was sheer media manipulation by a master. It backfired, of course, but [Pauline] Kael’s comparisons of [Gimme Shelter] to Triumph of the Will may be more apt than the Maysleses would like to admit. Jagger wanted to be filmed strutting the stage as the emissary of the Dark Lord before his adoring masses. The Stones were determined to star in their own extravaganza. The people at Altamont were simply unwitting participants in their titanic vision.

Jagger’s decision to avoid Sears Point Raceway set in motion a chain reaction of ultimately disastrous events. Selvin writes that “The inside of the track created a huge bowl effect with a twenty-foot rise at the end that, sculpted by a bulldozer, would make a perfect setting for a stage. It would provide a natural barrier between the audience and the stage.” Thus, a stage only four feet high off the ground was constructed, unlike Woodstock’s 15-foot high stage, which as Selvin noted, “served as a natural defensive barrier that prevented the fans from interfering with the musicians onstage. A high stage kept the audience in its place, making it an easier beast to tame.” But the last-minute move to the Altamont Speedway didn’t allow for time to build a taller stage. This in and of itself led to so many of the nightmares that the Maysles’ cameramen captured during the concert.

The Longest Day

Selvin’s descriptions of the actual day of the concert read like war reportage. If Cornelius Ryan had written up Altamont, the style of writing wouldn’t be much different.

Selvin begins by noting:

The drug scene had changed drastically in the two years since the Summer of Love. The original psychedelic chemists had been on a mission. They’d scrupulously made the purest LSD they could. Owsley Stanley was especially finicky. He manufactured special batches like his famed Purple Haze. Hendrix dropped a double dose before his set at the Monterey Pop Festival. But as LSD rapidly spread beyond the small contingent in San Francisco and Berkeley, the manufacture of the illegal drug shifted to less zealous chemists who were unafraid to take shortcuts and didn’t mind turning out inferior product…Some chemists added the poison strychnine to the recipe because it was said to extend the length of the trip. Some threw speed into the mix, which led to overstimulated users. One common symptom of speed-laced LSD was people stripping off their clothes and going naked.

Along the way, Selvin mentions the outcome of the two naked, LSD-tripping fat people who prominently featured in the Maysles’ movie:

The injured were littered backstage like wounded soldiers. The Angels kept a cordoned-off area as a jail where they held especially unruly concertgoers under guard. They had found the naked fat man and took out his teeth with pool cues. He wandered around, still naked, his face and chest dripping with blood. The [Flying Burrito Brothers] had hidden him in their trailer for a while. Likewise the naked woman who kept hugging people was beaten. She walked around backstage, also bloodied and still naked, but dragging behind her the blanket they had given her at the medical tent.

Aftermath

After the concert was over, Jagger, not surprisingly, was focused on himself. “Jagger, too, may have been shaken by the day’s events, but he still kept his eye on his more private needs,” Selvin writes. “He had attracted the fancy of Michelle Phillips [of the Mamas and the Papas, who had attended Altamont as a guest of country-rock pioneers the Flying Burrito Brothers, an opening act] and sent her ahead down to his room. Jagger waltzed [legendary L.A. groupie] Miss Pamela into the hallway, where he slipped his tongue into her mouth and suggested she join the two of them for a three-way. She declined and said good night to Jagger in the hallway. She didn’t want to share him.”

As Selvin points out, the Rolling Stones, though still massively popular to this day, were something of a creative spent force after Altamont. “The Stones would play out their days like tigers in the shade, challenging neither themselves nor their audience. Instead of a cultural force, the Stones settled for being caricatures of themselves, a raucous and colorful but ultimately meaningless sideshow, prancing on stage with props, costumes, and elaborate stage sets in cavernous football stadiums, no more simply five men and the music.”

There’s much truth there. I saw the Stones, along with 45,000 others, on Tuesday, Nov. 2, at the aging Cotton Bowl Stadium in Dallas, and apart from the cold, drizzly weather, and traffic jams leaving the stadium, the actual show ran like clockwork. Jagger, at age 78, is still a rail-thin dynamic performer with an “unexpectedly” lush head of hair and brilliant dance moves, even under the drizzle — he simply widened his stance, slowed down his footwork slightly, and concentrated more on flailing his arms about, to reduce the risk of crashing onto the stage — which, while not at Woodstock-level heights, was lined with plenty of (non-Hells Angels) security guards.

Incidentally, there is another sense of déjà vu looking back at Altamont: It took place during the Hong Kong Flu pandemic — as did Woodstock. “[I]n addition to Woodstock, 1969 was a huge year for concert festivals. The 2nd Isle of Wight festival took place weeks later, and the infamous Altamont Speedway festival took place in December…right in the middle of the 1968-69 flu pandemic’s 2nd wave,” Phil Magness wrote in a tweet last year that was included in an article by fellow American Institute for Economic Research member Jeffrey Tucker that was headlined, “Woodstock Occurred in the Middle of a Pandemic.”

In the 1960s, the Stones promised danger. Today, on their ironically titled “No Filter” tour, they promise family-friendly entertainment — even self-censoring their classic 1970 song, “Brown Sugar” — which was first performed live at (you guessed it) Altamont. A concert at which the Stones and their fans got far more danger than they had bargained for.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member