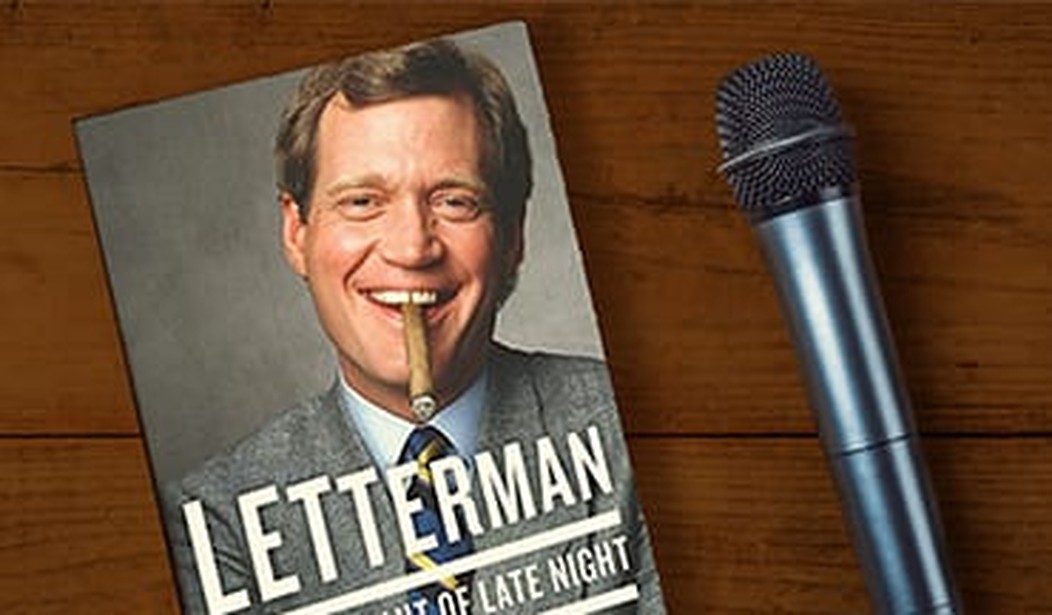

In 1980, Fred Silverman, flailing and failing at his efforts to bring to NBC the same golden touch he displayed at first CBS and then ABC, offered young David Letterman a morning TV show, an abortive effort that would ultimately morph into his long-running late night show. During a brainstorming session, Silverman told the young stand-up comedian that his show should be structured like Arthur Godfrey’s old TV show from the 1950s. Letterman winced at the idea, Jason Zinoman writes in his new biography Letterman: The Last Giant of Late Night, both because of how corny it sounded and because “I liked Godfrey,” Letterman said, “until he started firing people on the air.”

The moment in 1953 where Arthur Godfrey sacked popular young crooner Julius LaRosa on air was one of the first examples America saw of how the power of a network show can twist the mind of its host, causing him to lose all humanity, perhaps because he thinks that no matter what his excesses, he’ll never lose his audience. However, by the time Letterman retired in 2015, he had several moments on the same scale, if not arguably worse than Godfrey’s. Zinoman mentions some of Letterman’s creepiest, such as crude on-air flirting with supermodels, and a self-loathing alter-ego character called “Creepy Dave” who would appear on screen using videotape and split screen and silently stalk Letterman-Prime. As Zinoman writes, “Peter Lassally, who produced The Tonight Show, said he found Creepy Dave truly creepy. ‘It’s that stare— something very unpleasant. Dave tells him to get out, but Creepy Dave won’t go. It could be Dave’s conscience, I don’t know.’”

Prior to launch of Creepy Dave was Angry Dave. Helping NBC executives decide to give the post-Carson Tonight Show to Jay Leno was this incident:

Whereas Leno was friendly and approachable, Letterman was distant, even hostile. NBC’s president, Warren Littlefield, had no personal relationship with him. Brandon Tartikoff, his predecessor, had told him, “You can’t have a meal with Letterman.” When he asked why not, Tartikoff said he was not “comfortable having food with people.”

In an attempt to make a connection with the star, Littlefield had once sent Letterman a crystal decanter as a present. Letterman took the gift, put it on his desk during one show, and explained what it was to his audience, then proceeded to smash it with a hammer on the air. It didn’t endear him to his bosses. “It was a little shocking to me,” Littlefield said decades later, the memory still fresh in his mind. “He intimidated me.”

Backstage, Letterman intimidated and angered many of his writers with his behavior. Perhaps the most shocking backstage incident that Zinoman reveals involves Letterman’s attempted manipulation of the woman who did the most to launch him towards the big time. In the early 1980s, Merrill Markoe, a burgeoning sit-com writer whom Letterman dated since shortly after moving to Hollywood in the previous decade, created many of the elements that defined NBC’s Late Night with David Letterman. By the end of the 1980s her relationship with Letterman had ended, she was gone from the show, and once Letterman lost the opportunity to replace Johnny Carson, most of her comedic innovations were largely jettisoned or greatly watered down, in an effort to create a more mainstream 11:30 PM show at rival CBS.

Around the mid-2000s, longtime Letterman staffer Barbara Gaines contacted Markoe, telling her that Dave would like her to write a new segment for the show. Intrigued, she asked what he had in mind. Gaines replied: “Have you seen a segment we do called Stephanie the Intern?”

Markoe had not. Gaines explained that it was a regular segment where an intern named Stephanie Birkitt talks to Letterman, and in this case she would file reports from the Olympics, just as his mother had done, to much success. Gaines described Birkitt as a fish-out-of-water character. “Dave thought you could write her segments,” she said. Markoe asked about the pay. Gaines said the budget was tight, and the talks of her returning fizzled out.

Several years later, in 2009, news broke of a sex scandal on the Late Show. David Letterman had been threatened with blackmail by the boyfriend of a staffer with whom he was having an affair. The staffer was Stephanie Birkitt. When Merrill Markoe heard this news, her mind flashed back to the talk with Gaines. David Letterman wanted her to write jokes for the intern he was having an affair with behind the back of his wife, the former staffer whose affair helped end her relationship with him? Markoe’s mind reeled. “I felt like Bugs Bunny the time that Daffy Duck woke him up by putting the lid of a pot on his head and beating it with a spoon,” she explained. “I could feel my eyes rolling in different directions, and my head vibrating back and forth like a tuning fork.”

Ultimately, Markoe would go on to sardonically write on her blog, “As you can imagine this is a very emotional moment for me because Dave promised me many times that I was the only woman he would ever cheat on.”

As one Letterman staffer quoted by Zinoman says, “There comes a moment when he turns on you.” It’s brutal, revelatory stuff, but curiously, Zinoman leaves out one of Letterman’s worst moments, this one on-air. It happened in 2006, and by then, I had largely stopped watching most long-form TV – increasingly since the late 1990s, I was staring at a computer monitor all day, both finding material to blog about and writing up articles for magazines and material for the Web. But if Letterman was on in a hotel room while traveling, I had no qualms about leaving him on in the background.

And then Letterman had Bill O’Reilly on as a guest. While sparring, O’Reilly asked Letterman a simple question: “Do you want the United States to win in Iraq?”

Shortly before Barack Obama took office, Townhall’s Douglas MacKinnon wrote of the moment where Dave truly dropped the Carsonesque Midwestern boy made good mask, “To the surprise of no one but his sycophants, Letterman could not or would not answer the question. When pressed by O’Reilly to answer, the best he could do was to play to his mostly left-leaning audience for cheap debating points and say, ‘It’s not easy for me because I’m thoughtful.’”

Or as I added at the time, “How thoughtful do you need to be? it’s an A or B question: Do you want the US to win, or Al Qaeda, the Baathists, and Iran? Letterman, who, 20 years ago, was once the master of postmodern irony, became its unintentional victim as he unwittingly echoed Jack Benny’s classic gag when he retorted to a fictional mugger shouting ‘Your money or life, pal!’ on his old radio show: ‘I’m thinking it over!’”

Of Johnny Carson, Rob Long once wrote, “Johnny appeared on television every weeknight. He was playing himself—or, rather, an idealized version of himself: jovial, chummy, witty, warm. The strain of that kind of acting must have been monumental. It’s no wonder that real movie stars—Jimmy Stewart, Michael Caine, a whole bushel of A-listers—respected him so much. In one of the best stories in a book filled with great stories, when Johnny arrives late to a very exclusive industry event filled with movie stars, he lights up the room. He wasn’t just the king of late night television. He was the king of managing not to appear like the rat bastard he clearly was.”

Zinoman quotes one of the producers of Letterman’s NBC Late Night series describing Letterman’s personality and on-air role on that iconic show: “a man in a suit and a tie surrounded by madness.” Eventually, as it did to Carson, the madness, or at least the ego-driven anger that invariably seems to follow when a network hands a performer the key to the kingdom, would reach Dave as well.

For fans of television history, Zinoman’s biography is quite an interesting read, placing Letterman’s show in context with the late-night mavens who came before him at NBC – Steve Allen, Jack Paar, Carson, and Lorne Michaels’ Saturday Night Live. As Zinoman notes, Letterman’s iconic 1980s series was essentially Steve Allen’s old show with a postmodern twist, and a contempt for television it wore on its sleeve.

Early on, Zinoman quotes Gerard Mulligan, one of Letterman’s longest-lasting writers, on the premise of Dave’s ironic appeal, one that would ultimately lead to an overdose of irony, snark, and nihilism in the American media overculture: “I am just wasting your time and mine, telling pointless anecdotes, just making stuff up here. And yet you’re watching. Who’s the fool?”

Some of us figured that one out sooner or later. Actually, a lot of people; Letterman’s ratings at CBS in his last years were often dismal; as the New York Daily News noted a month before Letterman’s network retirement, Jimmy Fallon’s “success over Letterman is so complete, he’s not only beating him in terms of sheer ratings, he’s creaming Letterman with the most important group of viewers: people between the ages of 18-49, who are prized by advertisers.”

There’s something about giving a man the ultimate prize on television – his own late-night network show – that turns ambitious show business personalities into isolated monsters. It happened to Godfrey; it happened to Carson, and eventually, it happened to Letterman. But it’s telling that either the author, who writes the New York Times’ “On Comedy” column, didn’t think it mattered as much, or pulled his punches to protect his subject.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member