In The Who’s classic anarchic 1979 “rocumentary” The Kids Are Alright, there’s a film clip of a 23-year-old Pete Townshend, on tour in America in 1968, babbling on to an interviewer that “Pop music is crucial to today’s art, and it’s crucial that it should remain art, and it is crucial that it should progress as art.” In the 1960s, the loquacious Townshend was endlessly generating interview quotes about rock as a form of pop art. He derived this attitude through his studies in the early 1960s at Ealing Art College in West London. As Dave Marsh wrote in Before I Get Old, his 1983 history of the group:

In the fall of 1961, Ealing Art College was Pete Townshend’s salvation…The British art school system, although called a college program, was actually a part of the government’s vocational education system. Peter Blake, the pop artist who would later become the designer of album covers for both the Beatles and the Who, began art school in the late forties. “If you failed your initial examination, then a year later you could take an examination for technical school,” he said. “This is where you would go to learn bricklaying, technical things. But if you passed for technical school and you wanted to go to art school you could do that.” In consequence, art schools tended to attract a great many students who, were bright, lacked academic aptitude or discipline but hadn’t the patience to learn a trade.

* * * * * * * *

At Ealing simultaneously with Townshend were Ron Wood, of the Faces and the Rolling Stones; Freddie Mercury, of Queen; and Roger Ruskin Spear of the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band. John Lennon, Ray Davies, Eric Clapton, Keith Richard, Ian Dury, Bryan Ferry and many other British pop stars also studied in art schools during the late fifties and sixties.

* * * * * * *

As a vocational training institution, Ealing Art School was a failure as was the entire British art school system, since it churned out far more students than there were jobs. But simply by having such a powerful impact upon the development of rock & roll, which was to become Britain’s most important form of mass cultural expression over the next two decades, the art schools served their purpose.

It’s tempting to suggest that art school had more impact on those musicians through its exposure of a bohemian sensibility than through what was learned in class. But that is not borne out by the development of British popular music in the next few years, especially the hard rock of such bands as the Beatles, the Kinks, the Rolling Stones and the Who, all of them led by art school alumni.

As Jimmy Page, who attended Surrey’s Sutton Art College in southern London in the early 1960s, told Brad Tolinski of Guitar World magazine decades later, “Remember, just about any British band that came out of the sixties worth its salt had at least one member that went to art college, which was a very important part of the overall equation.”

It’s fitting then that a few of Townshend’s guitars, Keith Moon’s massive 1967-’68 era “Pictures of Lily” double bass drum kit, and a couple of John Entwistle’s bass guitars are part of the sprawling “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll” collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York that runs until October 1.

There’s a stodgy part of me that’s not thrilled that a museum that’s known for art dating back to ancient Egypt and Rome currently has several rooms stuffed with guitars owned or previously owned by Townshend, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton, Eddie Van Halen, Jimi Hendrix, Muddy Waters, Chuck Berry, Prince, Joni Mitchell and other rock and blues superstars. My immediate reaction to the collection was along similar lines to Peter Tonguette’s comments in a 2014 Weekly Standard article appropriately titled “Slighting Downhill,” after the Kennedy Center honored the surviving members of Led Zeppelin, complete with then-President Obama present:

In its first 20 or so years, the Kennedy Center Honors—annually allocated to performing artists of purported preeminence—there were more than enough leading lights still living to assure that the well of meritorious honorees would not quickly run dry. While there is truth to Frank Rich’s observation, in 1995, that “this country, like any other, has a limited supply of Balanchines and Grahams and Astaires and Sinatras,” for years it seemed as though figures of such prominence did, in fact, grow on trees.

* * * * * * * *

Rock stars are now regularly storming the gates of the Opera House: Tina Turner (2005), Brian Wilson (2007), Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey (2008), and—God help us—Led Zeppelin (2012). Indeed, of Led Zeppelin, [Caroline] Kennedy [the Kennedy Center’s MC] was impelled to read the following:

With primal sounds at once beautiful and dangerous, these English lads built a band that gave a new dimension to rock, and that earned from an admiring world a whole lotta love.

It got worse. Later that evening, a bedraggled Jack Black lumbered onstage and hollered “Led Zeppelin!” at the top of his lungs to kick off the tribute. We are a long way from Larry Hagman introducing singing midshipmen for Mary Martin.

And with “Play It Loud,” we are a long way from Rodin’s Burghers of Calais.

“Scream Power” Versus the Rock & Roll Arms Race

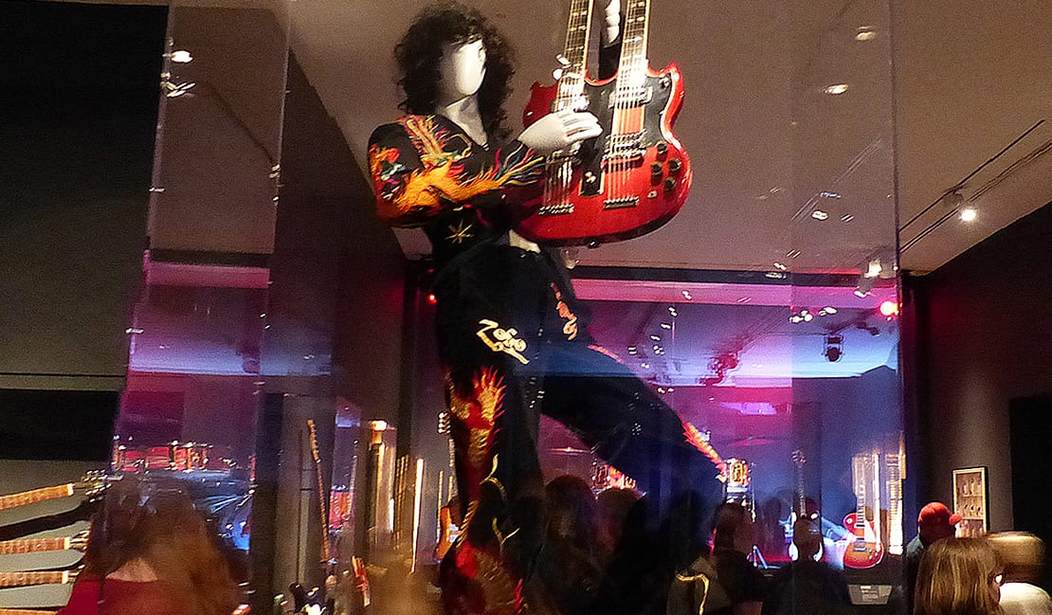

But hey, the Met is displaying Jimmy Page’s double neck Gibson guitar — the one he used to play “Stairway to Heaven” and “The Rain Song” and “The Song Remains the Same” onstage each night in the 1970s! And Eric Clapton’s well-weathered “Blackie” Fender Stratocaster, his primary touring guitar in the 1970s and ‘80s! And Keith Emerson’s massive Moog synthesizer and its spider web of patch cables! And Ringo’s drumkit and John Lennon’s Rickenbacker guitar and both Don and Phil’s matching Gibson Everly Brothers acoustic guitars. And much more! Who isn’t game to see these instruments close-up?

In addition to the double neck Gibson and the dragon suit, his “Number One” circa-1960 sunburst Les Paul Standard, his primary stage guitar since mid-1969 and likely worth a million dollars or so if it was ever sold, is on display here. A “black beauty” 1960 Gibson Les Paul Custom, which Page used heavily during his mid-1960s session-man days, and recently recovered after it was stolen during Zeppelin’s 1970 tour of America is displayed.

For Jimmy Page, now age 75, the Met’s exhibit is a double valedictory, both because of his own art school background, and because of Led Zeppelin being attacked by critics in their early days. (Rolling Stone magazine published particularly vicious reviews of their first albums.)

“Play It Loud” is something of a tribute to the rock and roll “arms race” of the 1960s, as amplification increased in wattage to compete with the roar of the audience, and stage guitars became flashier to give them something to look at. In a 1971 interview with Rolling Stone, Keith Richards colorfully described what the British invasion actually sounded like in most concert halls: “scream power”:

There was a period of six months in England we couldn’t play ballrooms anymore because we never got through more than three or four songs every night, man. Chaos. Police and too many people in the places, fainting.

We’d walk into some of those places and it was like they had the Battle of the Crimea going on, people gasping, t*ts hanging out, chicks choking, nurses running around with ambulances.

I know it was the same for the Beatles. One had been reading about that, “Beatlemania.” “Scream power” was the thing everything was judged by, as far as gigs were concerned. If Gerry and the Pacemakers were the top of the bill, incredible, man. You know that weird sound that thousands of chicks make when they’re really lettin’ it go. They couldn’t hear the music. We couldn’t hear ourselves, for years. Monitors were unheard of. It was impossible to play as a band on stage, and we forgot all about it.

By the mid-1960s, guitar amplification had achieved a quantum leap: England’s Jim Marshall invented the 100-watt Marshall stack, originally for John Entwistle and Pete Townshend of The Who. Soon, Jimi Hendrix, Cream, and eventually Led Zeppelin and Eddie Van Halen were famous for an enormous backline of amps and speaker cabinets behind them. The amplifier stacks of Jimmy Page, Eddie Van Halen and Rage Against the Machine’s Tom Morello can be seen at the Met, as well as the double neck guitars of Page and Don Felder, formerly of the Eagles, who trotted out his white Gibson double neck for the show-stopping “Hotel California.” Rock author Rikky Rooksby once described the double neck as “the rock equivalent of the Lancaster bomber.” But by the time of punk rock in the mid-1970s, the double neck guitar became somewhat camp-appearing, until Rick Nielsen had a deliberately ridiculous- looking five-neck guitar custom-built in 1981 — which is also part of the Met’s exhibit.

A five-neck guitar used by Rick Nielsen of Cheap Trick is displayed at the exhibit “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll,” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Monday, April 1, 2019. The exhibit, which showcases the instruments of rock and roll legends, opens to the public on April 8 and runs until Oct. 1, 2019. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

But things can be deceptive in the studio. While Jimmy Page had a stack of Marshalls behind him on stage, a tiny unassuming Supro 1690T Coronado amp with microphones carefully placed in front of, and even behind it, was the source of his massive guitar sound on the first Led Zeppelin album, along with a 1959 Fender Telecaster. A reproduction of his hand-painted “dragon” Telecaster is available for $1,299 in the obligatory gift shop at the end of the exhibition.

There are some drawbacks to the exhibit. The room is lit somewhat darkly, and as is typical with museum exhibitions, flash photography is not allowed, so leaving the exhibition with a digital device full of photos can be a challenge. And in today’s era of bitter social media, any exhibition will draw criticism for who or what isn’t included and how the history of the art in question is curated.

Before the Great Forgetting

And of course, to bring us back to young Pete Townshend’s comments at the beginning of our discussion, is rock and roll actually art? All popular music is surprisingly ephemeral. My father owned a massive collection of big band records, the superstar musicians of the 1930s until the arrival of the Beatles in America in 1964. After he died in 2006, we couldn’t give the stuff away. Their successor genres, bebop, cool jazz, modal jazz, and jazz-rock fusion have all come and gone, and its emissaries are becoming increasingly forgotten as time progresses, and the internet makes culture more and more present tense. Or as Kyle Smith dubbed it in January, “The Great Forgetting”:

These days, in a cultural sense, the only two pre-1960 singers who still linger in the memory are Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley. Bing Crosby, as Terry Teachout recently pointed out in Commentary, has more or less disappeared. A case could be made that, in addition to being one of his era’s most popular singers, Crosby is the single most popular movie star in Hollywood history. Certainly he is in the top ten. Today he survives in the memory of specialists and historians and suchlike boffins. To the broader populace, the words “Bing Crosby” no longer have meaning.

* * * * * * * * *

As the Who suit up for what I suppose will be their final tour (“Who’s Left”?), Chuck Klosterman points out in his book But What if We’re Wrong? that whole forms die out. He compares rock to 19th-century marching music: nothing left of the latter except John Philip Sousa. That’s it. And Sousa himself is barely remembered. In 100 years rock might be gone too, Klosterman guesses. Maybe we’ll remember one rock act. Who will it be? Maybe none of the obvious answers. It certainly wasn’t obvious at the time of Fitzgerald’s death that The Great Gatsby would be the best-remembered novel he or anyone else wrote in the first half of the 20th century. As for the novels of the second half of the 20th century, the clock is ticking on them. The Catcher in the Rye is moribund. Generation X was the last to revere that book. Teaching it to young people today would get you ridiculed. To Kill a Mockingbird? It had a good run but it’s now being labeled a “white savior” story by the grandchildren of those who revered it. Soon schools and teachers will be shunning it.

While rock could be tossed into pop culture’s dust bin within a century, in the meantime, it’s not surprising that the Met is flattering their aging visitors by creating a pop-oriented exhibition that flatters their taste. Classic rock is a far cry from classic art, but the Met’s new exhibit is undeniably fun.

Instruments used by members of The Beatles are displayed at the exhibit “Play It Loud: Instruments of Rock & Roll” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, Monday, April 1, 2019. The exhibit, which showcases the instruments of rock and roll legends, opens to the public on April 8 and runs until Oct. 1, 2019. (AP Photo/Seth Wenig)

Join the conversation as a VIP Member