In the movie The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Gandalf orders Pippin to climb a tower and ignite a signal fire to call Rohan to the aid of Minas Tirith. In a relatively short amount of time, the signal travels over mountains and vast distances, reaching Rohan, a sequence that was totally cool.

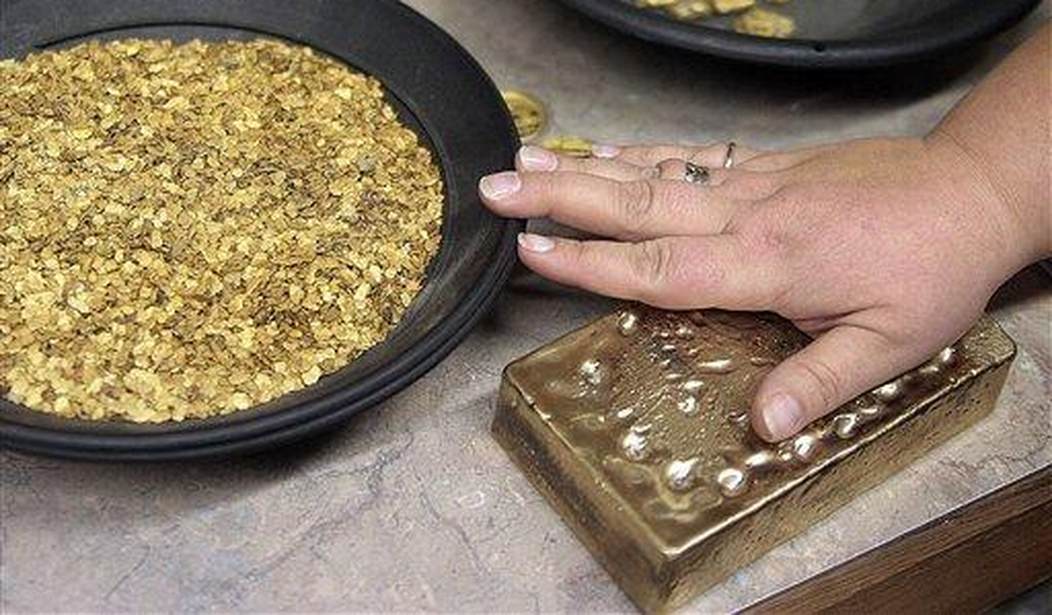

America had a similar signal, not fire, but gold. On Jan. 24, 1848, gold appeared at Sutter’s Mill, along the American River in California. Within months, people from every direction were pulled to California in search of hopes and dreams: farmers left their fields, clerks abandoned their ledgers, and sailors deserted their ships.

No single event in the nineteenth century moved Americans across the continent at such a large scale, with that speed, or for a single reason.

How a Remote Discovery Became a National Stampede

While working for John Sutter, the owner of Sutter’s Fort, James Wilson Marshall discovered gold. Initially, Sutter tried keeping things quiet, but failed miserably.

By 1849, word spread across the country and beyond, promising instant wealth that would overcome distance, danger, and doubt.

In his annual address to Congress, President James K. Polk confirmed the discovery, validating the rumors that sparked a migration explosion. Over 300,000 people poured into California within a few years, arriving by any means possible around the time of 1850.

No land rush or other federal program ordered that migration, just gold, alone.

Why Gold Moved More People Than War

While the Civil War mobilized armies, the Gold Rush mobilized people. Lincoln’s assassination shocked the country, but it didn’t uproot families or redraw settlement patterns. Gold did both.

People crossed plains, deserts, and oceans because gold offered something rare in American history: voluntary risk on a massive scale, where entire communities relocated without the government ordering them to. Men left homes, women followed later, and children grew up on trails and in boomtowns.

Although westward expansion existed before 1848, that trickle of movement transformed into a flood.

California Became a State at Breakneck Speed

California sat on the margins of American attention before the discovery of gold. After its discovery, California raced toward statehood as the population surge forced a rapid political organization. California entered the Union in 1850, skipping years of territorial development that other states needed to work through.

Almost overnight, the city of San Francisco transformed from a small port into a major city. Infrastructure closely followed migration: roads, ports, banks, and courts emerged as people demanded order amid the ongoing chaos.

Gold forced the federal government to catch up with its people.

The Costs That Followed the Rush

The California Gold Rush delivered opportunity and devastation in equal measure, as Native American communities suffered displacement, violence, and population collapse, while the damage to the environment scarred rivers and hillsides. Lawlessness thrived before civility caught up.

Those costs and scale matter because there wasn’t a single event in the 1800s that drew America in such numbers, so quickly, and for reasons rooted in individual choice rather than national command.

Gold simply didn’t rewire geography; it rewired incentives.

Why the Gold Rush Still Matters

America still runs on movement driven by opportunity, while the Gold Rush established a pattern of migration chasing economic promise instead of ideology, an instinct that built railroads, cities, and markets across the continent.

The promise of gold didn’t just populate California; it accelerated America’s transformation into a continental power, compressing decades of expansion into a few frantic years.

Washington didn’t plan that shift; its people did.

Final Thoughts

Jan. 24 marks more than a simple discovery; it marks a moment when Americans are willing to uproot everything for a chance at a better life. Gold generated momentum that wars, speeches, and laws never matched.

When the fire signal spreads, people move, and history follows.