I have been curious regarding how little effort the gun-control crowd has been exerting to prove that mandatory background checks work. There are, after all, six states that require all-private party sales to go through a background check, and ten states that require it for all handgun purchases. If driven to advocate for mandatory checks, you would think the case studies of these sixteen states must have provided plenty of evidence that such laws reduce murder rates, and thus affected your decision. Right?

I found this testimony to the U.S. Senate by Dr. Daniel Webster, a public health professor, from a few weeks back – he claims that Missouri’s repeal of its permit-to-purchase law (which required police approval of all firearms purchases) increased murder rates. His testimony claims that the increase was directly tied to the repeal of the law:

In 2008, the first full year after the permit-to-purchase licensing law was repealed, the age-adjusted firearm homicide rate in Missouri increased sharply to 6.23 per 100,000 population, a 34 percent increase.

That is a pretty startling increase, but several aspects of the claim made me start sniffing the air for fertilizer.

First of all, notice that this claim includes only firearms homicides. People stabbed to death don’t matter? It turns out that while Missouri’s murder rates (from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports) did indeed rise from 2007 to 2008, it was a 24% increase, which while still disturbing, is not as disturbing as 34%.

Secondly, when public-health specialists talk about “firearms homicides,” they do not necessarily mean criminal acts. The Centers for Disease Control database, which both Dr. Webster and I are using, has two different categories for intentional killing of another person with a firearm: “homicides,” and “legal interventions.” It is very clear that at least some of the deaths in the “firearms homicides” category are not crimes, but lawful uses of deadly force. The number of “legal intervention” firearms homicides deaths is so low — 45 from 1999 through 2010 for Missouri[1] — that it almost certainly represents only police officer killings, and does not properly include other legal interventions.

A longstanding problem with murder statistics is that some defensive killings are initially charged as murder or non-negligent manslaughter, and are reported to the FBI and CDC as such. A startling number of defensive gun uses are only reclassified days, weeks, or even months later, as the criminal justice system slowly works its way to an answer. At least with the FBI’s data, if that reclassification does not happen before the calendar month is over, it stays on the books as a murder or manslaughter.

I suspect that the same is true for CDC’s data. While there is an element of misfortune when a rapist or armed robber gets shot to death, this is hardly the tragedy that Dr. Webster’s testimony brings to mind when you read “firearms homicide.”

Thirdly, how “sharply” did the repeal of the “permit-to-purchase” law in August of 2007 increase firearms homicides? In other words, was it immediate and thus more likely tied to the repeal?

Here’s a graph of firearms homicides from CDC’s data for 2007 and 2008, by month[2]:

It took eight months before the “sharp” increase took place.

So perhaps the repeal of the law in August 2007 is not related to the increase.

St. Louis Public Radio ran a series of programs in late 2008 specifically about the increase in gang violence — including murders — that had lately plagued the city.

Perhaps this is the real cause. Of course, it is possible that the gangs had been unable to obtain guns before the repeal of the permit-to-purchase law, but forgive my skepticism in not buying that the gangs waited eight months to take advantage of the new law.

Fourthly, when I look at the rate for all murders and non-negligent manslaughters (the data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports program), I find that the increase in murder rates (not just with those icky guns, but with knives, fists, and other weapons) is not quite as impressive as the 34% figure Dr. Webster used.

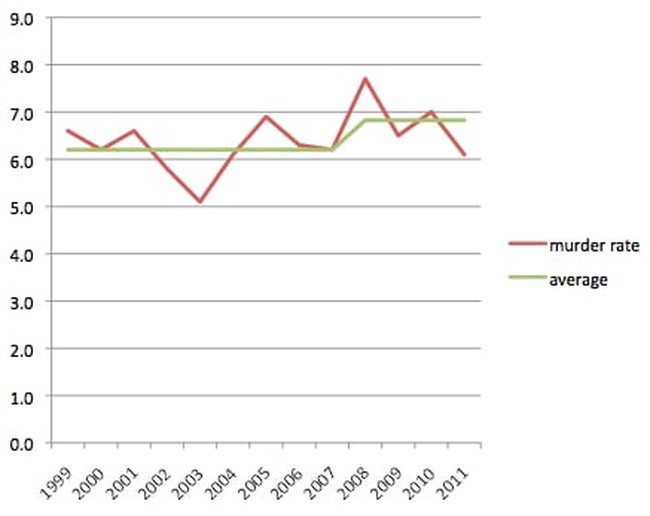

In the four years after the law was in effect (2008-2011), Missouri had a murder rate 10% higher than the period 1999-2007. And again: the FBI’s murder rates include at least some killings later determined to be lawful use of force. It is possible that some of the apparent increase in murders was because easier access to firearms meant more dead rapists, robbers, and murderers; at this point, we really do not have enough data to know for sure:

The most serious problem with the testimony: the increase in murder rates is not statistically significant at the 95% confidence level commonly used in the social sciences.[3]

Thus, it could be entirely coincidence that murder rates rose starting in 2008.

It is possible that the repeal of the permit-to-purchase law increased murder rates, but with the data now available, it is more likely a coincidence.

I really do have some sympathy for those arguing for background checks. There are people who should not have access to a gun: the severely mentally ill, convicted violent criminals, people awaiting trial for very serious crimes. I do not doubt that at least occasionally, background check laws prevent or at least delay such persons from purchasing firearms. (Many years ago, the county where I lived in California had a for-hire murder trial — involving a crossbow. It appears that the mental midgets who were hired for this job could not figure out how to buy a gun illegally.) But I rather doubt that this level of incompetence is the norm among criminals, who much prefer stealing guns to buying them. (Stolen guns are cheaper, for one thing, and there is no waiting period.)

Before we go down the road to requiring all private sales of firearms to go through a background check — either imposed nationally or at the state level — I would like to see some persuasive evidence that such laws actually reduce murder rates.

[1] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2010 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2012. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2010, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Mar 20, 2013 10:36:49 PM. ICD-10 Codes: Y35.0 (Legal intervention involving firearm discharge).

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. Underlying Cause of Death 1999-2010 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released 2012. Data are from the Multiple Cause of Death Files, 1999-2010, as compiled from data provided by the 57 vital statistics jurisdictions through the Vital Statistics Cooperative Program. Accessed at http://wonder.cdc.gov/ucd-icd10.html on Mar 20, 2013 8:42:25 PM. ICD-10 Codes: X93 (Assault by handgun discharge), X94 (Assault by rifle, shotgun and larger firearm discharge), X95 (Assault by other and unspecified firearm discharge).

[3] For 1999-2007: standard deviation is .524; for 2008-2011: .690. The 95% uncertainty range for 1999-2007 is 5.80 to 6.60; for 2008-2011, 5.73 to 7.92. Formal test of the null hypothesis shows no difference between the two means. Thanks to Professor Bruce McCullough for assistance with the statistical analysis.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member