As I’m writing this, Rep. Kevin McCarthy (R-Calif.) just lost his eighth vote to fulfill his lifelong dream of becoming speaker of the House. For all of the weeping and gnashing of teeth, the whole situation is kind of funny — as long as your name isn’t Kevin McCarthy.

It’s been a heck of a week for Congress, and it’s the first time in a century that the vote for speaker went beyond one ballot. But if these folks want to set a record, they have a long way to go.

A lot of the one-and-done nature of selecting a speaker over the past few decades has much to do with the dominant two-party system, but before the 1860s, multiple ballots were common. History shows us that eight votes for speaker went more rounds than this one has gone so far. Six contests went into the double digits, but the longest fight for speaker went a whopping 133 rounds and took about two months.

It all started with the disintegration of the Whig party in 1855, which left no single dominant party in the House. The country was starting to splinter over the issue of slavery, and factions in favor and against slavery in Congress tussled for control. When the House convened on Dec. 3, 1855, to choose a speaker, 21 candidates from several parties put their names into the mix.

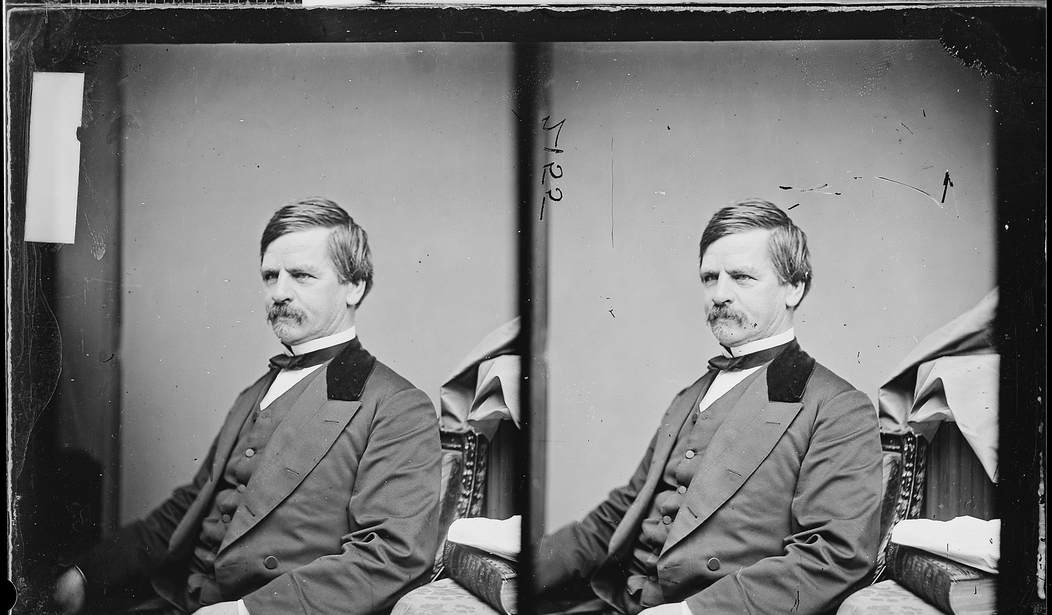

Pro-slavery Rep. William Richardson (D-Ill.) was the early leader, but he couldn’t muster a majority of votes. Anti-slavery members began to coalesce around Rep. Nathaniel “Bobbin Boy” Banks (American Party-Mass.), a young teetotaler who started his career in the textile industry, where he earned his nickname.

(Side note: we don’t give our representatives nicknames like “Bobbin Boy” anymore. Maybe that’s the problem, and doing so would make them more humble.)

As the votes continued, Banks began to garner more votes than Richardson, but neither one of them could summon a majority of votes. By the 33rd vote, Banks had 100 of the 113 he needed to secure the speakership.

“This is not a mere contest as to a Speaker of the House; it is but an incident in a long and arduous struggle which is to determine whether slavery will be the pole star of our National career,” read an editorial in the New York Tribune at the time.

As the votes dragged on, Horace Greeley, a Banks supporter and publisher of the Tribune, suffered an attack as he was leaving the House chamber in January. (Keep track of the time; that’s a month into the voting process.)

“A burly man approached the Tribune publisher and ‘struck me a stunning blow on the right side of my head and followed it by two or three more, as rapidly as possible,’ Greeley wrote,” according to the Washington Post. “The attacker was anti-Banks Rep. Albert Rust (D-Ark.).”

By the beginning of February — that’s right, two months in — another Democrat candidate emerged. Rep. William Aiken Jr. (D-S.C.), the son of a Southern railroad magnate, began to gather support. The Democrats planned to advance a resolution to elect a speaker on a plurality, since Aiken appeared to have the support of 109 members.

President Franklin Pierce expressed his congratulations to Aiken, and as the morning of Feb. 2 dawned, there was a growing hope that the long, drawn-out process would be over.

That afternoon, Rep. Samuel Smith (D-Tenn.) proposed the plurality resolution, but first, the House would vote. Banks won 103 votes to Aiken’s 95, prompting another vote. The House then voted to pass the plurality resolution and vote again. The final vote: 103 for Banks to 100 for Aiken. The Democrats’ plan had backfired.

In his address to Congress that night, Banks noted that his new job was “now environed with unusual difficulties.” He wasn’t kidding; in his one term as speaker, he watched Congress and his country slide further into disunity. Banks would later join the Republican Party, win election as governor of Massachusetts, serve as a general in the Union Army, and win another election to Congress in the late 1880s.

Here’s hoping the current battle for the speakership won’t drag out that long.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member