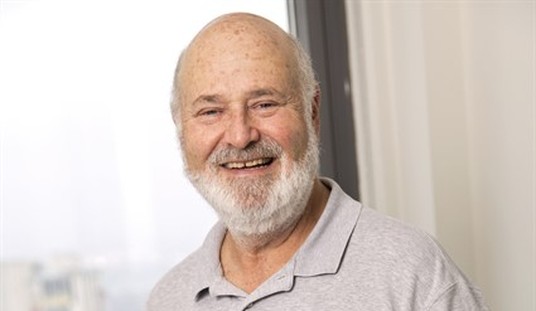

Reporter Bashar Fahmi was working for U.S. broadcaster Alhurra when he went missing two years ago in Syria.

The beheading of American journalist James Foley — and the grisly video of the crime that showed ISIS terrorists threatening to next kill Miami native Steve Sotloff — raised a chilling question: How many other hostages might be in the clutches of the Islamic State?

The tragedy has raised awareness of the reporters who have gone missing in Syria, with their whereabouts and captors unknown.

Foley, who was taken in northwest Syria on Thanksgiving Day 2012, was widely believed to originally be in the hands of Bashar Assad’s forces before the Islamic State video was released. Sotloff was taken near the Turkish border on Aug. 4, 2013, and his appearance at the end of the Foley video was surprising to many. His family had kept the story dark, hoping a media blackout might give them better negotiations with his captors.

In a June letter smuggled out by a released prisoner, then dictated from memory to Foley’s mother, the war correspondent described sharing a cell with 17 others. He said they shared stories and played makeshift board games such as Risk from scraps found in the cell. A British expert on Syria studied images of the terrain in the video and determined the site of the execution to be in the hills south of Raqqa, capital of the caliphate.

The Committee to Protect Journalists estimates about 20 journalists are missing in Syria, but the number of Americans — particularly if other families are imposing a media blackout on abductions as Sotloff’s family did — is unknown. A U.S. official told CNN after the Foley murder that the number of Americans held by ISIS is believed to be several, including kidnapped aid workers.

Foley’s murder instantly piqued concern for Texas native Austin Tice, a Marine Corps veteran who wrote for McClatchy Newspapers, the Washington Post, and other outlets. Tice went missing Aug. 14, 2012.

On Sept. 26 2012, a video titled “Austin Tice still alive” was posted on a pro-Assad website, and raised alarms about the Syrian government’s potential role in his capture. Foreign policy experts and Syrian natives alike agreed that everything from the poor production quality to the costumes and chants seemed staged to look like jihadi yokels, calling out “God is great” while leading a blindfolded Tice up a hill. Tice stammers an Arabic prayer followed by, “Oh Jesus, oh Jesus.” The video ends abruptly.

There were no demands accompanying the video, also a suspect sign, and the Syrian regime has denied any involvement in Austin’s capture.

“I think the Assad regime thinks Austin is a high-value asset that can be traded for some concessions,” one Syrian opposition source told PJM in December 2012. “…The fact they staged the video is a signal that they want to use him but without the PR burden of being associated with his kidnapping. To go through this means they value Austin.”

On Thursday, the Free Austin Tice account on Twitter tried to allay fears about whether the Marine was in the hands of ISIS.

“We have kept this account silent as everyone mourns the loss, & celebrates the life, of the irreplaceable human being who was James Foley,” the account tweeted. “And we will continue to remain in the background, as people worldwide come together in support of the family of James Foley, & of the families of all those foreign & local hostages still held by IS, of which Austin is not one.”

Tice’s parents, Marc and Debra, released a statement on the 14th saying they are “continually unsettled by disturbing questions about his welfare.”

“To those holding Austin, we ask you to treat our son well and return him to us safely and soon. Austin is a man of good character, and his effort to tell the world about what is happening in Syria – from all perspectives – is honorable,” they wrote. “We will not give up; we want to see our son safely home. May it be soon, according to God’s will.”

In addition to Americans missing in Syria, though, is a foreign national who was working for American-funded Alhurra.

The Broadcasting Board of Governors issued a plea Tuesday, the same day that the Foley video was released, for the release of a reporter for Virginia-based satellite broadcaster who went missing in Aleppo on Aug. 20, 2012.

Bashar Fahmi, a Jordanian national, was kidnapped along with Turkish cameraman Cüneyt Ünal. A video of a battered Ünal was released a week later, and he was released by the Syrian government in November 2012.

But there’s still been no sign of Fahmi.

“No one could have imagined that two years after that tragic day, there would still be no word about Bashar,” Brian Conniff, president of the Middle East Broadcasting Networks (MBN) that oversees and manages Alhurra Television, said in a statement Tuesday. “This has been incredibly trying for Bashar’s wife Arzu and their children, as well as his Alhurra family.”

“I implore anyone with information about Bashar to come forward,” Conniff added. “We condemn attacks on any journalist. These are dedicated professionals who are reporting in difficult situations and Bashar’s trip to Aleppo was no exception.”

Soon after releasing the statement on Fahmi, news of the Foley murder broke and the BBG released another statement.

“Such horrific acts demonstrate utter disregard for human rights and justice,” said Jeff Shell, chairman of the BBG. “Journalists such as Mr. Foley risk everything to enlighten people around the world with the true picture of what is happening in conflict zones. Killing and threatening journalists does nothing but cover up the true story and demonstrate how brutal some of its actors are.”

Shell echoed the call for Fahmi’s release.

Fahmi’s wife waits for him in Turkey, where on Tuesday she tweeted that she was going back to the Syrian consulate in Istanbul to protest.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member