It’s time for folks in New York City — and more broadly from the Delmarva to Cape Cod — to recognize that a hurricane with genuine potential to produce severe devastation is mere days away. (In North Carolina, it’s closer to hours away; bad weather will begin early Friday. But I think folks there already know that.)

It’s still not at all clear exactly where in the northeast Irene will go. (Here’s a video from The Weather Channel presenting the different scenarios, and another video explaining the steering factors that will determine which scenario happens.) But for everyone in the threat zone, and most especially for folks in the highly vulnerable Big Apple, the time to prepare is now. That includes being prepared to leave, at least if you’re in a low-lying coastal area and/or evacuation zone. You need to be ready to potentially leave town as early as Thursday night or Friday morning, when I expect evacuations will begin if the track forecast doesn’t decisively shift eastward in the next 24 hours. (Side note: Although the storm would not hit until Sunday, with no serious adverse impacts likely until Saturday night at the earliest, I predict the New York Stock Exchange will be closed on Friday, barring such a track shift, in order to facilitate evacuations and begin clearing out Lower Manhattan. You heard it here first.)

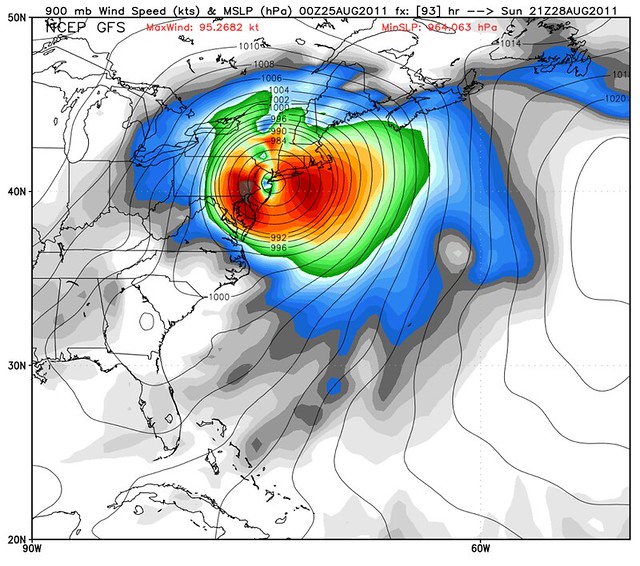

It’s also time for NYC’s local officials to stop pretending that a Category 1 hurricane strike is the “worst-case scenario” for their city. That sort of false reassurance, masquerading as a warning, is deeply unhelpful. The simple fact is, most people aren’t going to be scared, still less spurred to action, by the words “Category 1 hurricane.” Of course, I wouldn’t advocate unnecessarily scaring people if a potential Cat. 1 was truly all we were dealing with — but it’s not. It’s been clear all day today that something far worse, while perhaps still unlikely, is very much within the realm of realistic possibility for New York City… and that’s only become clearer this evening. Take a look at the latest prediction by the GFS model, the most reliable and accurate American computer model in existence:

Holy hell. That map is downright terrifying. (It’s even worse when viewed as an animation. Hat tip: Ryan Maue.) It represents something pretty darn close to the true worst-case scenario, the New York nightmare that experts have feared for years — a Category 2 hurricane, perhaps even a low-end Cat. 3, making landfall in New Jersey, and pushing a severe storm surge into New York harbor, with devastating effects.

I emphasize again that this is just one possible scenario among several, and probably not even the most likely. But such scenarios are always unlikely, right up until the point when they’re about to happen — at which point it’s too late to prepare for them! So everyone needs to prepare as if they’re going to suffer a direct hit, and not just by a minimal hurricane, but by a monster. (And if that preparation proves, in retrospect, to have been unnecessary, breathe a sigh of relief and know that you were right to prepare for the worst, not blithely assume the best.)

What I just said applies to everyone in the threat zone — basically, the entire East Coast from the Carolinas to Maine, though what proper “preparations” mean will vary greatly based on local conditions — but my focus here is on Gotham. That’s not because New York is the most likely landfall target (the most recent GFS run notwithstanding, Long Island and Cape Cod are at least as likely, and of course Cape Hatteras is the most likely, and will experience Irene first), nor because New Yorkers are intrinsically more important than anyone else. Rather, I’m focusing on New York simply because it — like New Orleans, Miami and a handful of other American cities — is unusually vulnerable to hurricane devastation, and also unusually unprepared for it. Quoting from the Wall Street Journal last year:

To learn about New York City’s last direct hit from a severe storm, you’d need to look all the way back to 1893, when a so-called “West Indian Cyclone” carried sailing ships to Sixth Avenue, created a river on Canal Street that briefly connected the East River and the Hudson, swept much of Coney Island into the sea and entirely destroyed a barrier beach called Hog Island that once lay south of the Rockaways in Queens.

When–not if, say experts–it happens again, a storm will find both New York and Long Island far more populated than the last time. In the city, a hurricane’s storm surge would cause sudden, extensive flooding, submerging much of Lower Manhattan and crippling the subway system and tunnels.

The powerful winds would uproot thousands of trees, down power lines and send debris flying in all corners of the city. And those winds could shatter windows on skyscrapers, especially in the taller buildings that would bear the brunt of powerful gusts that occur at higher elevations. The canyons of Manhattan could magnify the winds, and would be a deadly place for anyone caught beneath the raining glass.

Flooding may be more extensive in Brooklyn and Queens, and not just in Brighton Beach and the Rockaways. The city’s official map of hurricane evacuation zones warns that JFK and LaGuardia would see serious flooding in even a Category 2 storm; a Category 3 could send several hundred thousand residents from Dyker Heights and Canarsie, East New York and Laurelton in search of higher ground. So would people living in Mott Haven and Hunts Point in the Bronx, in East Harlem, and in coastal parts of Staten Island. …

In the most dire projections, a direct hit on New York City could cost upwards of $100 billion.

More from the International Business Times:

The single biggest effect New York City would see from a major hurricane is the storm surge. This is the term for water pushed toward the shore by high winds, and it can rise many feet above sea level and inundate entire neighborhoods. In the New England Hurricane of 1938, the storm surge from the East River flooded three blocks of Manhattan, even though the center of the hurricane was many miles away, pummeling eastern Long Island. The Norfolk and Long Island Hurricane of 1821 made landfall in the city itself — in Jamaica Bay, Queens — and the 13-foot surge inundated more than a mile of Manhattan from Battery Park to Canal Street. …

New York Harbor is narrow, which means that water rushing northward from the storm surge, with nowhere to go, would build up very high — as high as 30 feet, or the third floor of some buildings, according to past warnings from the city’s Office of Emergency Management. According to an evacuation map posted on the city’s official Web site, aside from Lower Manhattan, many low-lying parts of the other four boroughs would also be at risk, including LaGuardia Airport and J.F.K. Airport, which are located right by Flushing Bay and Jamaica Bay, respectively. All of this would be compounded if the storm surge happened at high tide. …

Every New Yorker has seen how messy subway stations get in heavy rain: dirty puddles form on the platforms, water streams from openings in the ceiling onto the tracks, and trains are frequently delayed. Now imagine even heavier rain, plus a storm surge that sent water from the rivers and harbors crashing into the stations through the stairwells, ceilings and tunnels. It would not even take a worst-case scenario to bring the entire New York City public transportation system to a standstill. In the short term, this would eliminate any chance of last-minute evacuations; in the long term, it could extend the economic damage of a hurricane even beyond when office buildings reopened. If the subways were flooded with saltwater rather than just rainwater, the salt “would corrode the switches and cripple the system for months or years, and disable much of the communications infrastructure in Lower Manhattan,” the Wall Street Journal reported in 2010 based on an interview with Nicholas Coch, a coastal geology professor at Queens College. …

Residents don’t necessarily understand “how many days and weeks after a hurricane that their lives will be completely changed,” Scott Mandia, a physical sciences professor at Suffolk County Community College on Long Island, told National Geographic News in 2006. “People who live away from the water think a hurricane will mean one day away from work, then back to normal. There will be an economic shutdown for a few weeks, if not a month.” He was referring to the impact of a hurricane on Long Island, but the impact on the Financial District would be even worse. A big storm surge could paralyze that part of the city for weeks, depending how severe the flooding was, how quickly the water receded and how much infrastructural damage it left behind, and the consequences of that would be far greater than just lost wages.

If it isn’t already obvious from reading that, it’s long past time for New Yorkers to drop any misconceptions that their city is somehow invulnerable to a crippling hurricane strike. While I emphasize again that it’s still possible that Irene will veer off to the east, or will spend too much time over land before hitting NYC and/or be too weak to cause devastation — hurricane forecasting is an uncertain business — the threat of a severe impact is very real. This is no mere hypestorm.

For those who remember me from Katrina, I’ll say that the “Get the Hell Out!” moment hasn’t arrived yet. But if we get to tomorrow night and things haven’t changed in the forecast… it may.

For now, Irene is still churning through the Bahamas. The mighty storm is going through an eyewall replacement cycle right now, preventing further strengthening — in fact, truth be told, she’s probably a bit weaker (temporarily) than the 120 mph sustained winds that the National Hurricane Center is officially listing — but once that cycle is complete, Irene is likely to pick up steam. She’s forecast to become a Category 4 hurricane tomorrow. She’ll weaken again before landfall, but the longer she stays as a Cat. 3 or Cat. 4, the bigger the storm surge she’ll push out ahead of her, worsening the eventual impact wherever she hits.

Bottom line, this is no time for complacency. Thursday is the last day for preparations before things will begin to get frantic. If you’re in the threat area, take advantage of it. That goes for folks in the local media as well: in an eerie similarity to Katrina six years ago, we’re coming up on the lazy final weekend in August; come Friday, many people will start tuning out the news if they don’t already know they need to pay attention. So tomorrow is the day to really drive home serious and genuine this threat is. No hype, no nonsense, just the God’s honest truth — that Irene is a serious threat to be reckoned with.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member