Did you miss the “good news” on May 12?

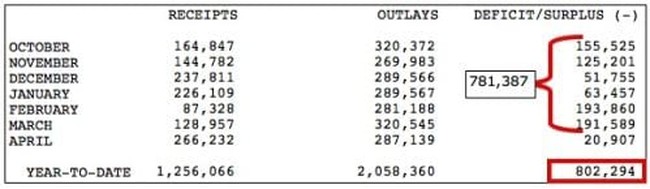

The Treasury Department, led by tax cheat Tim Geithner, retroactively reduced the deficit through March 31, the first six months of Uncle Sam’s fiscal year, by over $175 billion.

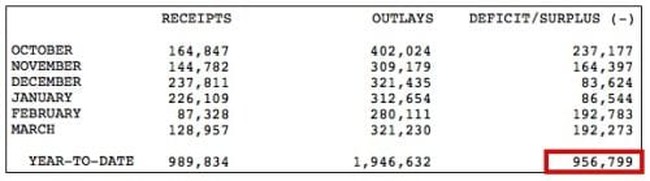

Here’s the evidence. March’s Monthly Treasury Statement showed a year-to-date deficit of $956.8 billion — but (voila!) April’s statement showed that the deficit through March was only $781.4 billion (items in red and October-March total box added by me):

Wow. How did Treasury do that?

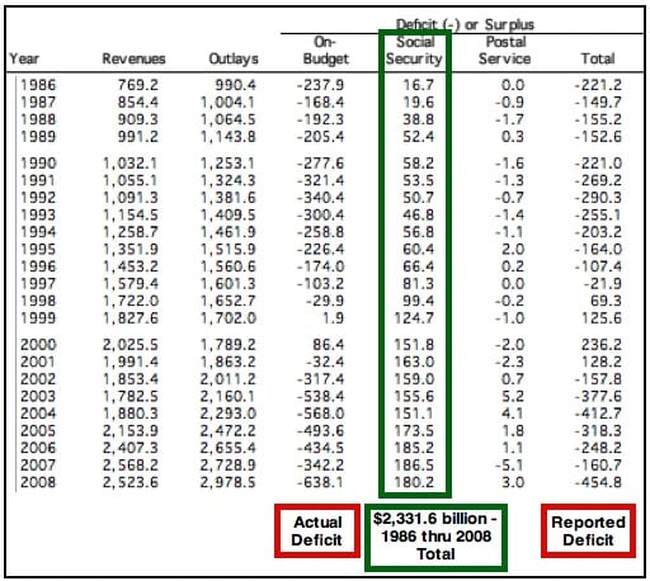

Before I provide the answer, let me first make clear that federal financial reporting has been much less than perfect for a long, long time. The problems started in the 1960s with President Lyndon Johnson’s “unified budget,” which combined the financial results of Social Security, the Postal Service, and the rest of the federal government into one presentation.

On the surface, that may have seemed like a good idea. But, as I’ve explained previously, Johnson’s decision ultimately enabled congresses and presidents of both parties to use Social Security collections in excess of benefits paid to paper over much higher deficits occurring in the rest of the government:

The $2.3 trillion in Social Security cash surpluses shown above has been “borrowed” from the Social Security “Trust Fund” and spent. The “Trust Fund,” far from being a stash of cash for paying out future benefits, contains almost nothing besides IOUs from the rest of the government, which is itself over $11.3 trillion in debt and counting. The “Trust Fund” can’t be paid without raising taxes, reducing benefits, or borrowing even more money. What’s more, the annual Social Security surpluses are disappearing and its cash flow may go negative as soon as 2010 or 2011. Recent news that many more workers than expected are choosing to begin collecting reduced benefits at age 62 is not helping matters in the short term, though it could be perversely helpful in the long term.

But let’s get back to Treasury’s April “magic.”

To understand it, you have to understand what Treasury says the Monthly Statement is supposed to tell us (saved here in case it gets revised or moved):

[The statement] presents a summary of:

- Receipts and outlays

- Surplus or deficit

- Means of financing on a modified cash basis

According to a 1990 law, the “means of financing on a modified cash basis” element of the statement requires certain government “investments” to be reported on a “net present value” (NPV) basis.

What’s that? Are you sure you want to know?

Well, okay. It’s the estimated value of appropriately discounted future cash flows.

Try to resist the MEGO (My Eyes Glaze Over) effect, because this will get very important pretty quickly.

Based on a discussion I had with a person in the Congressional Budget Office, the only major area where NPV accounting has been used is in the Education Department’s student loan programs.

Here is what Education does, either monthly or quarterly:

- Loans disbursed are deducted from the cash deficit; remember, they’re considered “investments.”

- Loan principal repayments are added to the deficit, because they reduce the amount “invested.”

- The interest portion of loan repayments is treated as income, reducing the deficit.

Finally, and much less frequently (either quarterly or annually), the department adjusts the value of its “investments” based on changes in interest rates and judgments regarding the loans’ ultimate collectibility:

- If rates have gone down, the loans’ “investment” value goes up and Uncle Sam’s reported deficit goes down. If rates have gone up, the opposite occurs.

- Improvements in collectibility prospects increase “investment” value and decrease the reported deficit. Deteriorating collectibility prospects have the opposite effect.

Aren’t you glad you asked?

Fortunately, student loans, though a significant problem in their own right, are a relatively small part of the leviathan known as the federal government. Thus, the difference between true cash flow reporting and Uncle Sam’s “modified cash basis” has been unimportant and the reported deficit, with the key exception of the Social Security problem previously discussed, has been a close-enough indicator of true cash flow.

That changed in October, thanks to the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP).

What Treasury did in April was to convert the TARP “investments” it began making in October in the country’s financial institutions, General Motors, Chrysler, and who knows what else to NPV accounting. That accounting change reduced the previously reported March deficit by $175 billion.

As you might have noticed, Barack Obama and Tim Geithner are not done “investing.” There are hundreds of billions of dollars in outlays yet to come that I anticipate Geithner will handle using NPV, including additional TARP “investments,” the toxic asset program, and perhaps the ever-expanding mortgage relief efforts. At some point, Geithner might even decide that the tens of billions disbursed to prop up Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac thus far also have “investment” value.

Mixing hundreds of billions of dollars of NPV into what has essentially been a cash flow report turns the Monthly Treasury Statement, and deficit reporting in general, into an exercise that will not only become ever more difficult to comprehend, but also be routinely subject to political manipulation. Judgments as to what discount rate to use, how collectible loans are, and even what should and should not be considered an “investment” will have multi-billion-dollar impacts on the publicly reported deficit. NPV might even directly affect policy. Why should Geithner or Obama allow banks chomping at the bit to get out from under TARP to do so, when their repayments will only increase the reported deficit? Already, the administration, which has projected a fiscal 2009 deficit of over $1.8 trillion, has avoided the political embarrassment of estimating a shortfall that would round off to $2 trillion using true cash flow reporting.

If Congress really cares about the euphemism known as transparency, it will pass legislation forcing Treasury either to change how it presents its Monthly Statement or to issue a separate all-inclusive monthly cash flow statement. Such a statement must lay out receipts and disbursements that occurred during the month, and nothing else. The difference must tie in to the net change in the national debt.

I somehow doubt that Nancy Pelosi or Harry Reid have any interest in this.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member